Overview

The Australian Government has commissioned an independent review to consider the capabilities of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). The Review is a forward-looking, whole-of-agency exercise that assesses ASIC's ability to meet its current and future objectives and challenges. It is not a performance review.

In undertaking the Review, the Panel consulted extensively with businesses regulated by ASIC, peak bodies, regional and consumer representatives, regulators and other stakeholders, as well as ASIC staff and leadership. The methodology of the Review involved extensive consultation, including stakeholder interviews, surveys of ASIC staff and stakeholders (the regulated population, business, consumers, and practitioners), discussions with peer domestic and international regulators, and assessment of public and internal ASIC documentation and data.

Overall assessment

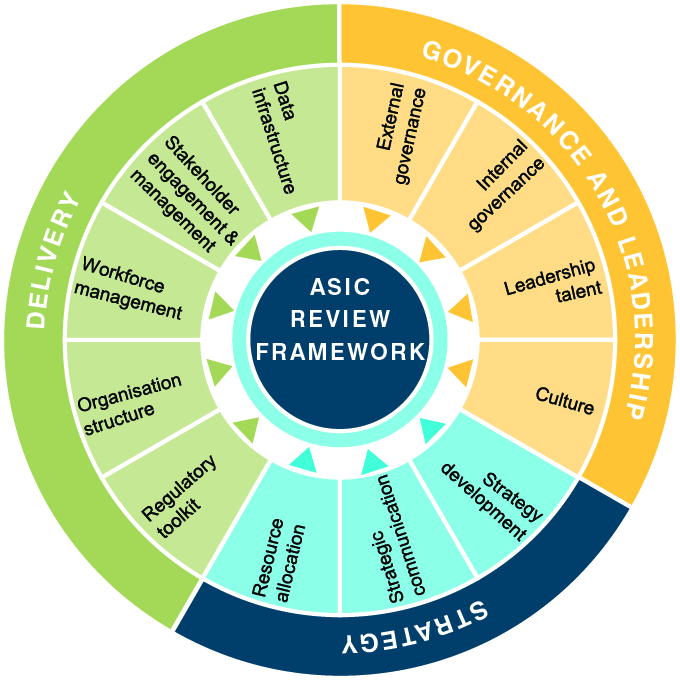

To examine and assess ASIC's capabilities, the Panel adopted a well-established and contemporary Capability Review framework focusing on the key elements of Governance and Leadership, Strategy and Delivery. Figure 1, provides an overview of the elements of the capability framework adopted as the basis of this review. Importantly, the framework has been refined by the Panel to reflect the capability requirements for conduct and security regulators (that is, what the Panel would expect a model regulator to look like).

Figure 1: Capability Review Assessment Framework

The Review has assessed ASIC across each element of the framework. This has involved a transparent and comprehensive fact and evidence-based approach. The Panel has drawn on the resulting fact-base and used its judgement to make observations and recommendations.

In order to ensure that the Review provides a set of useful recommendations for ASIC, the focus has been on areas for improvement. Accordingly, the discussion is relatively more focused on a forward looking identification and assessment of current shortcomings, while acknowledging but not elaborating on relative areas of strength. The Panel has been mindful of this tendency, and has sought to identify and acknowledge recent areas of improvement and where ASIC's capabilities are best practice or sound. That said, it is incumbent in undertaking the review that greater detail be afforded areas for improvement and the accompanying practical recommendations for action to address them.

Overall, and based on the Panel's extensive discussion with other regulators and experts who have reviewed those peer regulators over time, the Panel has found that the effectiveness and efficiency of ASIC's capabilities vary widely across the range of areas assessed:

- A few of the regulatory capabilities, such as real-time market supervision and consumer education, are in line with or at the forefront of global best practice.

- There are some areas where ASIC's approach is similar to the practices of peer regulators, and while these capabilities show some opportunities for improvement, appear broadly appropriate for current and future needs. Most elements of ASIC's regulatory toolkit (for example, surveillance, education, and policy guidance) fall into this category.

- A few capabilities are in line with those of most other regulators, but still behind where they will need to be to ensure that ASIC is fit for the future. The key areas here are application of 'big data' analytics to regulatory activities, building capabilities to respond to the challenges posed by technological and business model innovation in the financial sector, and in partnership with the Government, improving the use of ASIC's external accountability infrastructure.

- Finally, there are a number of areas where ASIC's capabilities show material gaps to what the Panel considers to be good practice, and where improvement is required without delay. These include ASIC's governance model and leadership related processes, its IT, data infrastructure and management information systems (MIS), for measurement and reporting of internal efficiency in management dashboards, and its approach to stakeholder management.

To ensure ASIC is fit for today and fit the future, ASIC and the Government must collectively address the gaps identified above, especially those in the latter two categories.

Common themes identified

The Panel has observed five key themes in its assessment of ASIC. These themes cut across the main elements of the capability framework (governance and leadership, strategy, and delivery), and draw together many of the observations highlighted throughout the Report. The themes are:

- sound governance architecture, not well used;

- the 'expectations gap' — much greater than expected;

- opportunity to reorient for greater external focus;

- cultural shift needed to become less reactive and more strategic and confident;

- 'future-proofing' and forward-looking approaches needed.

The Panel also observed some external constraints for which action needs to be undertaken.

Sound governance architecture, not well used

In a number of areas, the Panel observed that ASIC's 'governance architecture' (the setup of its key governance elements and processes) is sound and well designed, but for a variety of reasons has been used in a way that does not produce the best possible results.

A key example is ASIC's internal governance arrangements. While legislation requires that the Commission be comprised of three to eight statutory appointees, it provides only general guidance as to the roles that the Commissioners are to perform. Under current arrangements, Commissioners have both an executive (management) role and a non-executive (governance) role. In their executive roles, Commissioners have responsibility for a particular line of business, with direct reporting lines from Senior Executive Leaders (SELs) to individual Commissioners, and are involved in the management of day-to-day operations. In their non-executive roles, Commissioners provide strategic oversight across the organisation, ensure internal accountability and make decisions (including strategic and material regulatory ones) on a collective basis.

The current model has a number of strengths (for example, close alignment between operational and strategic decision making). However, the model also results in a number of key challenges and tensions, with the risk that it erodes the strength of internal accountability, and that it may leave insufficient bandwidth for Commissioners to focus on important strategic issues and external engagement.

The Panel believes that a dual governance and executive line management role inherently undermines accountability. Despite best efforts, individuals responsible for particular executive functions are unlikely to be consistently able to detach themselves from their concerns as an executive, to take a fully independent and organisation-wide perspective when acting in their governance role, to hold the executive team (including themselves) to account.

The conclusion that ASIC's Commissioners have insufficient 'strategic bandwidth' is supported by interviews and discussions with the Panel, together with the Panel's own observations and a time-use survey and analysis conducted by PwC. After having reviewed PwC's analysis and an advance draft of the Panel's Report, ASIC provided supplementary time-use data, which could not be reconciled with the information originally provided to PwC and presented a picture of greater time spent on strategic matters.

Regardless of the interpretation of the time-use evidence, the Panel is of the view that its findings stand given other sources of evidence (observations, internal and external discussions, sur

vey data) and challenges around ensuring strong internal accountability under the current structure. As a result, the Panel considers that the existing model is unsustainable, given the magnitude of the challenges ASIC is likely to face in the foreseeable future.

The combined non-executive and executive role is unlike the models employed by large corporations and many other conduct regulators internationally, where Commissioners or Board members do not have direct responsibility for a line of business and are not directly accountable for and immersed in day-to-day operations. It also has significant in-practice differences to the models deployed by the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) and also the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), including the latter delegating to a Chief Operating Officer (CoO), despite operating under similar legal frameworks to ASIC. The Panel therefore concludes that the concerning aspects of ASIC's governance model are not dictated by its 'structural architecture', but rather by the way the model is interpreted and applied by its leadership.

Similarly, ASIC has a broad range of external accountability mechanisms, including ministerial oversight, parliamentary oversight and inquiries, performance reporting and the Statement of Expectations (SoE) and Statement of Intent (SoI) documents. However, these are not being effectively used to provide an assessment of ASIC's strategic choices and effective delivery over time.

The Panel recognises that Parliament has an important role to play in investigating material regulator performance issues, including those that give rise to concerns of the public, and in ensuring that ASIC is identifying and addressing in a timely and effective manner significant risk issues that may result in material harm or potential harm . However, the Panel considers that, on balance, parliamentary oversight has tended to become overly issue driven and reactive, at the expense of a more strategic long term oversight function and comprehensive accountability. This view was shared by most stakeholders consulted and emerged as a common theme in stakeholder feedback during the review's consultation.

Additionally, the SoE and SoI are not being fully leveraged to ensure broad public understanding of what should be expected of ASIC, and what are the limitations of its mandate, particularly in relation to protection from harm. Overall, the Panel considers the external governance architecture to be comprehensive, sound and simply requiring better and more disciplined use.

As a third example, while a well-established strategic planning process exists that the Panel would consider to be sound 'governance architecture', there is insufficient focus on planning the delivery of the strategy. This is evident in the Corporate Plan which, while providing a thorough discussion of ASIC's objectives and priorities, does little to describe how these goals will be achieved. This is an essential prerequisite to accountability. It is also manifest in ASIC not having contemporary Management Information Systems (MIS) to facilitate efficiency measurement and management dashboard reporting or an established program of continuous business efficiency review and improvement. The absence of these systems precluded the Panel's assessment as to whether ASIC is efficient, appropriately funded and comprehensively reducing red tape.

The insufficient focus on delivery in the strategy is also partially driven by the combined executive and non-executive governance structure. A body that merges a whole of organisation strategic function, with individual executive responsibility, will be less easily able to require its individual members to detail and account for their plans than a non-executive board would be able to in relation to the executives reporting to it.

The Panel believes this can be readily addressed without changing the structure or needing an external Board.

The 'expectations gap' — much greater than expected

In a number of areas, the Panel identified and noted a misalignment between the understandings or perceptions of external stakeholders and those of the ASIC leadership (Commissioners and SELs). This misalignment can be referred to as an 'expectations gap', relating to both perceptions of ASIC's performance and what ASIC can and cannot do. It is to be expected that there will be some expectations gap — both because of an inherent 'negativity bias' by stakeholders in relation to a regulator, but also to some extent because of a 'positivity bias' on the part of leadership. However, for many reasons, the expectations gap was much greater than expected.

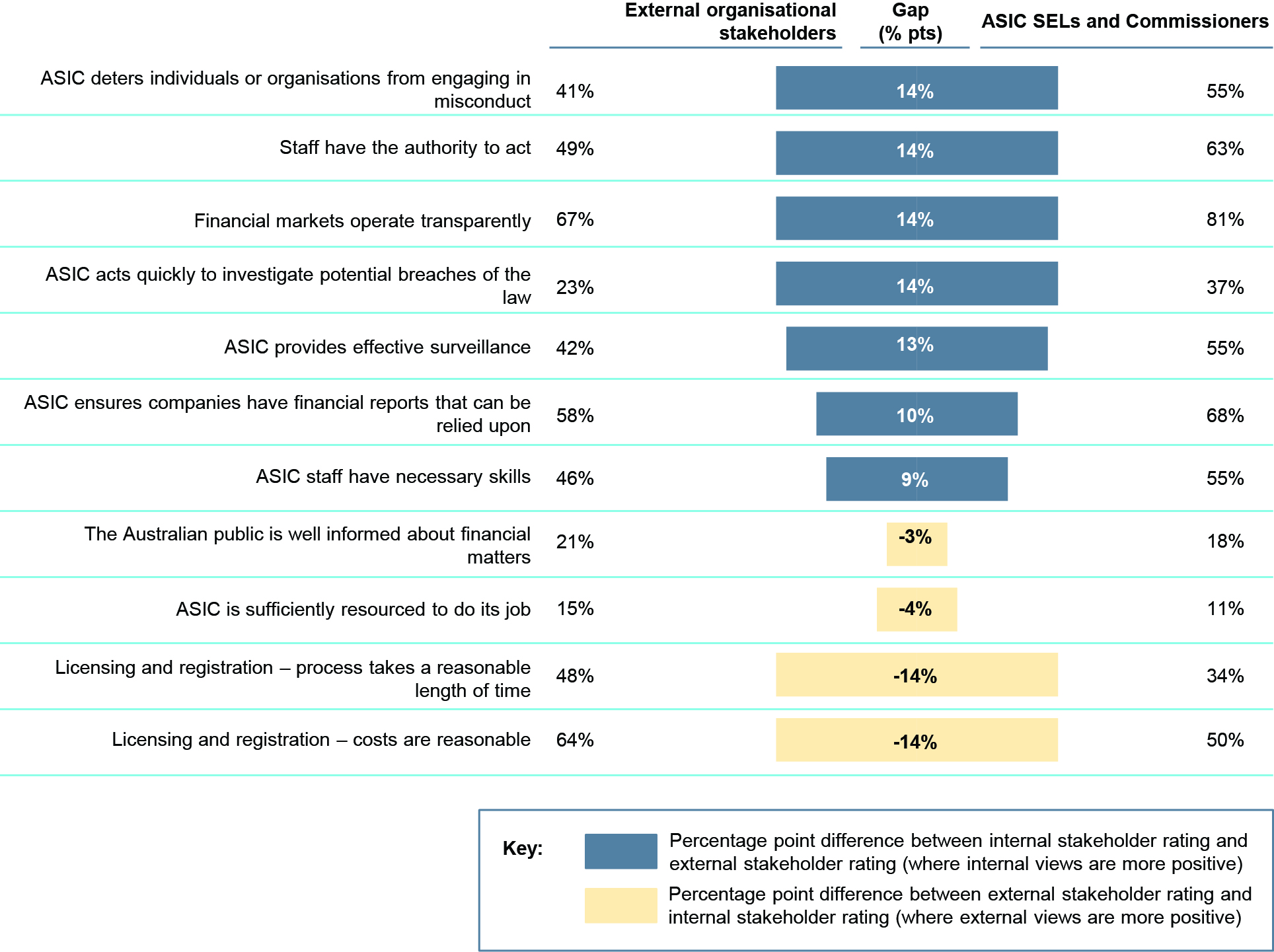

In surveys conducted as part of this review, there was close alignment (less than a 15 percentage point difference) on a number of the survey questions, and in some instances the views of external stakeholders were more positive than those of ASIC leadership, for example in the timeliness and cost of licensing and registration. These results are included in Figure 2, below.

Figure 2: The expectations gap — areas of alignment1

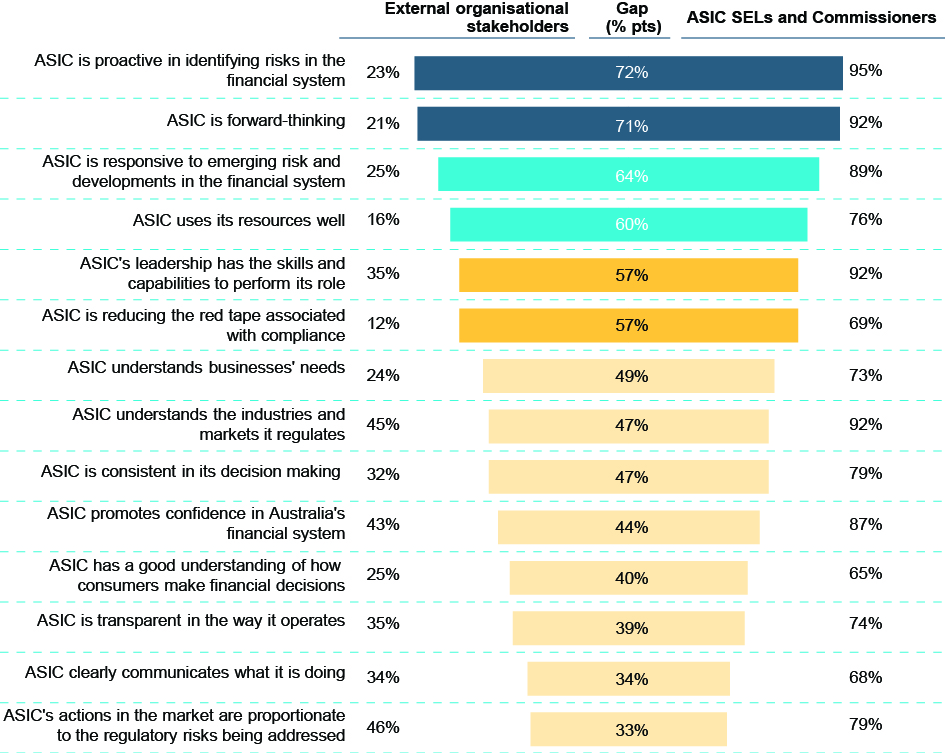

However, the Panel also identified a larger number of areas of significant misalignment (where ASIC leadership's survey results were more than 50 percentage points disparate to external stakeholder results) illustrated in Figure 3. The Panel observes the most significant expectations gaps occurs in relation to the extent to which ASIC is outward looking, proactive and forward thinking, and is responsive to emerging risks and developments. Stakeholders also expressed more negative views than ASIC leadership about its use of resources, and its success in cutting red tape (see Chapter 2 for further discussion).

Figure 3: The expectations gap — areas of misalignment2

It is also evident that many external stakeholders are not fully aware of the limits of what ASIC can and should do. This is demonstrated in the tendency for public reaction and criticism against ASIC where there is a market failure or losses occasioned by normal commercial or investment risks, even where it is not reasonable to expect ASIC to have prevented that outcome.

The expectations gap may not necessarily be indicative in itself of ASIC's performance, as it is based upon subjective judgement and not all stakeholders are fully informed or impartial. It may also indicate that ASIC has not been successful in communicating its achievements to the public, or that it has not fully grasped what is expected of it. For example, ASIC has been making progress on reducing red-tape, and is able to identify a number of specific examples where this has been successful, resulting in a total saving of around $470m. However, feedback suggests that this progress has fallen short of expectations and that ASIC may not be placing sufficient focus on the areas that impose the biggest regulatory burden (see Chapter 2 for further discussion).

The gap is much greater, however, than the anticipated disparity and warrants immediate attention to improve clarity over ASIC's mandate, ensure strategic responses are appropriate and to improve performance reporting. This imperative to act would be elevated if a proposed move to a user pays funding model is adopted by the Government.

The expectations gap also provides valuable indication of areas where ASIC either needs to improve its capabilities or where it needs to improve the effectiveness of its communication about its activities and the results. The Panel ha

s therefore used the expectations gap as an important guide to its focus areas during this Review. In particular, the Panel investigated drivers of the expectations gap and identified a number of these in ASIC's external accountability arrangements, strategy development and communication processes.

Opportunity to reorient for greater external focus

Across the various areas of governance and leadership, strategy, and delivery the Panel found that the organisation had an inward-looking orientation to its culture and practices.

For example, based on evidence prepared by ASIC and PwC, the Panel concludes that ASIC's leadership spends insufficient time engaging with the market3 and tends to be overly focused on internal challenges and operations. The PwC time use analysis suggests ASIC Commissioners spend 26 per cent of their time on external engagement4 (including engagement with international stakeholders), while evidence provided by ASIC suggests Commissioners spend on average 24 per cent of their time on the same.5 Excluding the Chairman, whose International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) role entails a significant time commitment, the average comes down to 21 per cent.6 The Panel views a best practice time allocation to external engagement for the senior leadership of a regulator as 40 per cent or more, based on observations of other agencies. The Panel believes that ASIC's governance arrangements contribute to this inward orientation for its leaders and that change is required to reorient them 'upward and outward' rather than 'downward and inward'.

The Panel also found that ASIC can do more to leverage a wider variety of perspectives to support the identification of emerging risks and trends to inform the selection of its strategic priorities. For example, while ASIC currently has an extensive set of external expert panels, the Panel has concluded that these are not currently being fully leveraged in the strategic planning process. Similarly, numerous stakeholders indicated that they do not feel ASIC is consulting them sufficiently as a means of proactively identifying emerging risks and priorities and tailoring regulatory solutions.

ASIC also has scope to be more outward looking in its interactions with regulated entities. Touch-points with the regulated population are driven primarily by ASIC's internal organisation model and the priorities of the individual teams within it, rather than the needs of stakeholders. Many of the larger and more complex regulated entities find ASIC's engagement with them uncoordinated and thus more burdensome than it needs to be. The Panel believes that a revised stakeholder management model would support greater outward orientation and more effective engagement with external counterparties.

Cultural shift needed to become less reactive and more strategic and confident

Importantly, stakeholder feedback and survey data indicates that ASIC staff are motivated, hard-working and professional. However, there is a stakeholder perception, supported by the Panel's observations, that ASIC has a tendency to be reactive in the way it uses the regulatory tools at its disposal and is often excessively issue driven (that is, responding to high profile events) rather than more consistently strategic in its focus.

The way in which current external governance arrangements are applied is a major driver of this tendency. Analysis of the public record of interactions between ASIC and its oversight bodies such as the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services show that these are overwhelmingly focused on topical issues (financial planning scandals for example), rather than on discussion of ASIC's longer term strategic plans and progress in delivering on these. The SoE and SoI documents also lack strategic depth and represent a missed opportunity to inject a more proactive element into ASIC's external governance process.

In the Panel's opinion, this heavily issue driven oversight is highly likely to contribute towards a reactive culture at ASIC. However, the Panel acknowledges that reactive cultures appear to exist broadly across the public sector. The Review of Whole-of-Government Internal Regulation found that risk aversion was a dominant aspect of institutional culture across the public sector. Of the 18 capability reviews of departments and agencies conducted between August 2012 and July 2014, 13 identified significant levels of risk aversion and centralised decision-making at senior levels.7

The Government and ASIC have a joint responsibility to recalibrate the reactive focus of ASIC's oversight to include a greater emphasis on holding the regulator accountable for delivery on a sound, forward-looking strategy. This change should result over time in a shift in ASIC's culture to greater proactivity and further promote staff morale.

It is ultimately the responsibility of ASIC leadership to set the culture and tone and to drive top-down messaging to ensure consistency across the organisation. Commissioners therefore need to articulate the required cultural changes in the organisation and ensure that these filter through into everything they do — here ASIC should look to be a role model in embracing the types of cultural improvement and maintenance programs that it is increasingly requiring of regulated entities.

Furthermore, ASIC's articulation of its role, especially by the leadership, shows too heavy an emphasis on enforcement, which is often a reactive tool. This is also reflected in ASIC's resource allocation to the enforcement function far exceeding that of peer regulators. This enforcement emphasis in communications and resourcing risks prioritising strategic focus and staff orientation too much towards this single aspect of the regulatory toolkit. While enforcement is a critical element of ASIC's toolkit, especially in terms of its deterrence impact and overall credibility of the regulator, in the Panel's view, a better balanced approach emphasising the full scope and use of ASIC's regulatory toolkit would be more appropriate for a modern and dynamic conduct regulator.

'Future-proofing' and forward-looking approaches needed

ASIC has done much to improve its capabilities over the last four to five years. It has recognised many of the gaps and issues identified in this Review and has launched a number of relevant initiatives, especially in the IT and data infrastructure area. In the Panel's view, such change programs need to be developed and rolled-out with ASIC's future as well as current needs in mind. Indeed, acceleration of these programs is likely to be necessary for ASIC to keep pace with the rate of change in the markets, products and services which it regulates.

Effective investment is essential for 'future proofing' ASIC's ability to meet future demands. This includes identifying the capabilities that are important now and in the next three to five years and ensuring ASIC has the required infrastructure to support closing these gaps.

Across the various aspects of this Review, it was not consistently apparent to the Panel that ASIC does take such a forward looking view in relation to its capability development efforts. For example, efforts to improve forward looking workforce planning only began in early 2014 and are not fully developed or embedded. This is currently being conducted with the assistance of an external service provider and do not cover support functions or forward-looking Commission level skills gap assessments.

Another example is the IT component of the OneASIC program (FAST2), which, while closing existing gaps, will likely still leave ASIC lagging compared to peer regulators when it is implemented. ASIC's planning around how it

will use its upgraded infrastructure to support 'big data' driven regulatory analytics also appears relatively nascent. It has initiated a process of working through these questions and assigned responsibility for charting a course for the use of data and analytics to the Strategic Intelligence Unit. This is an important step but its work in this area appears to be behind that of leading peer regulators and is not sufficiently advanced to credibly form the basis of a 'future-proofed' IT infrastructure plan in terms of specifying the data infrastructure needs of future analytics applications.

This issue was a focus of PwC's expert assessment of ASIC's IT programs. While PwC's report was purely a factual evidence collection exercise and did not include observations and judgement, the PwC expert conducting the IT assessment has reviewed the Panel's findings and agrees with the Panel's conclusions.

External constraints

The Panel also identified three exogenous factors (those outside of ASIC's control) that will impact on ASIC's ability both to respond to the recommendations made in this Report, and on its ongoing and future ability to fulfil its mandate efficiently and effectively. These are:

- Legislative and regulatory complexity: the increasing complexity of the regulatory regime that ASIC is expected to administer, and in particular the application of the Corporations Act, is a source of significant regulatory burden, constrains ASIC's ability to advance regulatory mutual recognition internationally and imposes material costs on the real economy, particularly in relation to Australia's competitiveness in attracting productive capital investment to fund future economic growth and employment.

- Perceived funding constraints: Like most government agencies, ASIC has experienced some funding instability and inflexibility in recent years, due to Government savings measures. There is also a perception of underfunding (although it is not clear whether this perception is well founded). The Panel notes that ASIC's real funding has increased from $260m to $312m since 2004-05 (excludes own-source income), largely reflecting the expansion of its functions over this period. Whatever the perceived funding constraints, it is incumbent upon ASIC to use its funds efficiently and effectively to deliver value for money for its funders and stakeholders. This will require ASIC developing and implementing contemporary MIS to measure and report internal efficiency metrics.

- Regulator cooperation: the potential limitations imposed through insufficient coordination and forward looking collaboration between peer regulator agencies. ASIC's Eight Point Plan indicates that ASIC is willing to enhance the degree of cooperation with other regulators and agencies.

Recommendations: thirty four actions identified

The Panel has approached this Review with the over-arching objective of ensuring that ASIC is 'Fit for the Future'. In doing so, the Panel has identified what action is needed without delay to ensure ASIC is entirely fit for purpose today. There are a number of changes that are needed to ensure that ASIC is sufficiently well governed, skilled, agile and responsive to meet the challenges of the future, both those that are already becoming apparent, as well as those that as yet remain unknown.

The Panel views ASIC leadership and the Government as ultimately and collectively responsible for the issues identified by the Review. As such, a mutual commitment to considering and implementing the Panel's recommendations will be needed. The Panel has identified a range of practical and action oriented recommendations to support ASIC in executing its mandate more effectively.

Thirty four recommendations have been identified across the different elements of the capability framework (that is, Governance and Leadership, Strategy and Delivery). Implementing the Report's 34 recommendations will require the collective action of the Government, the Parliament and ASIC. All of these recommendations are consistent with the IOSCO Principles of Securities Regulation,8 especially those relating to internal governance.

To deliver the change required, ASIC will need to begin implementing these recommendations immediately following the announcement of Government decisions on this Report. Most can be implemented within 12-24 months. Appendix A provides further implementation details of the Panel's recommended work-plan for change at ASIC.

While the Panel consider all 34 recommendations to be complementary and important, those relating to Governance and Leadership are the most critical and enduring and therefore matter most. In particular, recommendations relating to internal governance and leadership talent management will enable ASIC to effectively and efficiently execute its mandate while continuing to focus on strategic issues and external engagement. The Panel views these recommendations as essential prerequisites to securing the intended outcomes from the other recommendations. These recommendations are therefore important enablers for achieving broader change.

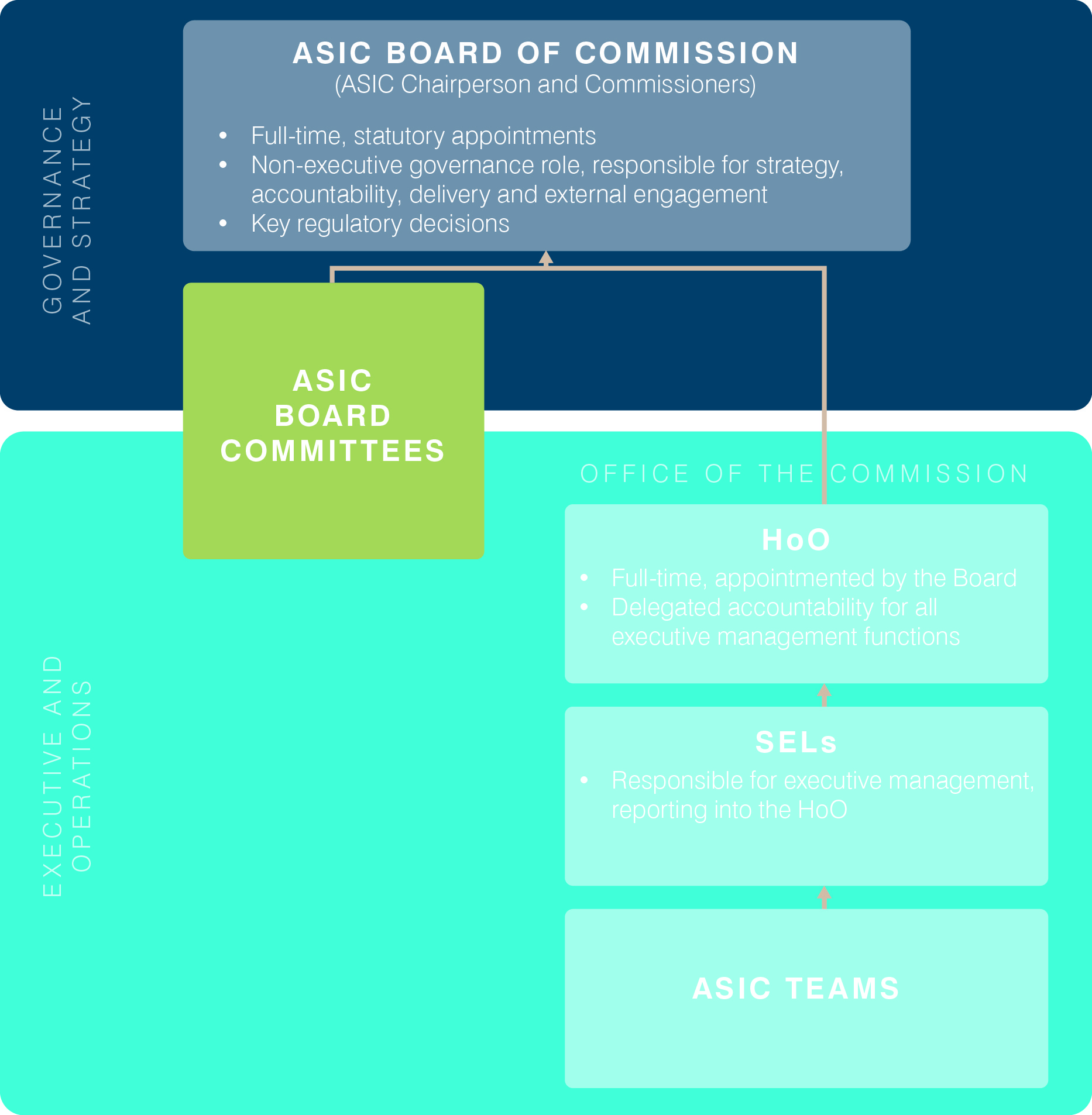

Firstly, the Panel recommends that ASIC realign its internal governance structure to achieve a clear separation of the non-executive (governance) and executive line management roles. This will improve internal accountability mechanisms, and increase bandwidth for strategic decision making and external engagement and communications. The primary focus of the Commissioners becomes setting the strategy of the organisation and supervising overall delivery and performance against the strategy, along with making, and taking ultimate responsibility, for key regulatory decisions.

The recommended model elevates the existing Commissioner roles to a full-time non-executive internal 'Board of the Commission' (not an external board), similar to the internal governance model of the ACCC.

In this proposed model, operational decision making and execution for operational matters is delegated to the Senior Executive Level (SEL) level, reporting directly into a new Head of Office of ASIC (HoO) role. The HoO will be selected by the Chairperson and Board of Commission and is delegated executive responsibility from the Chairperson. The Chairperson will retain ultimate accountability, and thus the model is consistent with legislative requirements.

The role of the HoO will be to lead the day-to-day operational management of the organisation and to relieve the Chairperson and Commissioners of these additional and operational responsibilities. SELs will either report directly into the HoO or via group leaders. Clear lines of accountability, a revised delegation framework, and likely a revised Commission sub-committee structure will all be required to ensure that the right issues are being elevated to the Commission.

A well-developed governance and oversight framework will ensure that the HoO does not become a 'bottleneck' on decision-making and is elevating key issues while addressing operational matters below the Commission level. As is the case in other regulators and many large organisations with external Boards, there will still be regular direct contact between the full-time Commissioners and SELs on strategic and important operational matters, both during Commission meetings to which relevant SELs would be invited, and more informally on a daily basis. However, the important difference would be the elimination of direct reporting from particular SELs to individual Commissioners, and hence the establishment of clear lines of accountability for executive line management functions.

Figure 4: Key features of the proposed internal governance structure

In the Panel's view, there are a number of significant ben

efits which make the proposed internal governance model superior to the current arrangements:

- The Commission and executive have separate and distinct roles, ensuring clearer lines of accountability and oversight, thereby enhancing overall accountability and efficiency at both levels.

- Primary focus of the Commissioners is on setting the strategy of the organisation, supervising overall delivery and performance against the strategy and making strategic and material regulatory decisions from a whole of entity perspective.

- Commissioners have a full-time focus across the whole organisation (rather than devoting part of their time to specific cluster responsibilities).

- Commissioners are separated from operational decision making and execution activities, thus avoiding potential conflicted interests and ensuring whole of entity objectivity.

- Commissioners can be more focused on managing 'upwards and outwards', that is managing external relationships with the Government and other external stakeholders, rather than being focused 'inwards and downwards', that is managing internal operations and relationships.

- The Commission has the organisational flexibility to allocate the oversight of particular components of the strategy to a subset of the Commissioners.

- The proposed model does not require legislative change for implementation.

The proposed model is consistent with the recommendations of the Uhrig Report on regulator governance in Australia, in that the Panel is not recommending creation of a Board of external, part-time directors for ASIC. Indeed, the role of the ASIC Commissioners will extend materially beyond the role of a non-executive director at a listed corporation. Under the new approach, ASIC's Commissioners will still be full-time and intimately involved in major regulatory decisions of strategic significance, for example approving policy recommendations and major enforcement decisions that are systemically important or high profile.

Furthermore as full-time Commissioners, there will be no risk of conflicts of interest driven by other roles, and no detachment from the business, as can occur with an external Board. There will be close interaction with ASIC senior executives on a daily basis, but Commissioners will have greater bandwidth to drive strategy, direction, culture and stakeholder management more effectively. This will allow the Commissioners to become genuine leaders rather than managers.

The Panel considers that there is a substantial agenda of strategic issues to be addressed by the Commission over the next three years, and that this will require their full-time attention, undistracted by direct involvement in managing day-to-day operational issues. These strategic issues cover the implementation of the internal governance changes; strategy setting; capabilities improvement; cultural transformation; change management and effective external stakeholder engagement.

The Panel acknowledges that the choice on the appropriate internal governance model for ASIC is ultimately a matter of judgement but current arrangements blur accountability. Therefore, the Panel has concluded that true accountability for ASIC will remain elusive in the absence of the proposed changes to its internal governance arrangements.

Secondly, the Panel recommends that Chairperson, Deputy Chairperson and Commissioner recruitment be based on a contemporary, competitive and merit based assessment process. This is important to ensure public confidence in the suitability of the Commission, and therefore ASIC more broadly.

Thirdly, the Panel recommends that the Government and ASIC commit to fostering a more strategic long term oversight function. This will include enhancements to the existing SoI and SoE infrastructure, more regular ongoing discussions between the Chairperson and the relevant Ministers, and a new commitment that the responsible Minister provide an Annual Ministerial Statement in Parliament to report on ASIC's overall effectiveness and performance. The Panel views the proposed enhanced standards as also providing a potential and helpful benchmark model for the Government's interactions with other independent statutory agencies and regulators.

The Panel views the Review's observations, findings and recommendations as broadly aligned with and a practical extension of the FSI. Consistent with past reviews, the Panel does not see the need for an external Board but has sought to advance and develop a more effective approach to internal and external governance.

The Panel considers that the proposed changes to internal and external governance practices offer potential for significant improvement in ASIC's capabilities without the need for any architectural change. The recommendations broadly align with other reviews conducted into the Financial System and ASIC. The Panel endorses the Government's position not to proceed with the establishment of a Financial Regulator Assessment Board (FRAB) — there is no need for 'another regulator to regulate the regulators'.

Further to the recommendations relating to governance and leadership, the Panel makes a number of recommendations on strategy and delivery — especially relating to strategic development and communications, resource allocation, workforce planning, organisation structure, the regulatory tool kit, and stakeholder and data management. Many of these recommendations are designed to better leverage both ASIC's internal resources, as well as external capabilities currently under-utilised.

Of particular significance, the Panel considers that there are significant potential widespread risks in the current licensing and registration system which fall short of desired standards and warrant the close attention of both the Government and ASIC. Accordingly, the Panel recommends greater use of co-regulation models by ASIC collaborating with relevant industry associations to lift professional standards and ensure a more robust and effective licensing and registration system.

Table 1 summarises the key observations and recommendations across each element of the capability framework. Each of these observations and recommendations will be discussed in the following chapters.

| Characteristic | Key observations | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

|

Governance and Leadership (Chapter 2) |

||

|

External governance (Section 2.1) |

While the design of the external governance and accountability architecture is appropriate, it is being applied in a manner which is unnecessarily reactive and issue driven, and is not providing broad long term strategic oversight and thereby accountability for ASIC. The SoE is infrequently updated and does not clearly or transparently establish strategic priorities as understood by the Government. As a result, there is an opportunity to update the SoE to ensure better alignment and mutual understanding. There is a significant 'expectations gap' between the internal and external perceptions of ASIC's performance, which must be managed by both the Government and ASIC, including through the SoE and SoI. ASIC is addressing its performance reporting under the PGPA Act, although this activity remains at an early stage and will need ongoing development (as recognised by ASIC in the articulation of its Corporate Plan). |

Recommendation 1: The Minister and ASIC to implement a more effective strategic long term oversight function, underpinned by a mutual commitment to a more pro-active regular ongoing dialogue. As steps to achieving this:

Recommendation 2: ASIC to continue to refine the performance reporting framework, including consolidating performance reporting (to ensure consistency between reporting frameworks), aligning internal performance metrics, improving the use of performance narrative, and identifying opportunities for more sophisticated analytics, particularly in relation to outcomes measures. |

|

Internal governance (Section 2.2) |

ASIC's non-executive and executive management responsibilities are combined, unlike separated (split or hybrid) models used at large corporations and many other international and domestic regulators. While the Panel understands the evolution of the current model and strengths and shortcomings of various alternatives, on balance it believes the current structure is unsustainable if optimal outcomes are to be achieved. In particular, it leaves insufficient bandwidth for the Commissioners to focus on strategic matters, external engagement and communication and does not provide sufficient internal oversight and accountability. The Panel considers that the Commission's strategic and oversight responsibility, coupled with its external engagement role, as meriting the full time focus of the Commissioners. |

Recommendation 3: ASIC to realign internal governance arrangements by elevating the current Commission role to that of a full time non-executive function (not an external board), with a commensurate strategic and accountability focus free from executive line management responsibilities. Recommendation 4: ASIC to establish a new role of Head of Office (HoO), with delegated responsibility and accountability for executive line management functions. Recommendation 5: SELs to be delegated executive line management functions, reporting to the HoO. Recommendation 6: Government to revisit this structure in three years, to review the size of the Commission and whether the roles of the Commissioners need to continue to be full-time. |

|

Leadership talent (Section 2.3) |

Merit based selection procedures exist but have not always been closely or fully followed by Governments in appointments of the Chairperson and Commissioners. While the collective capabilities of the ASIC Commission receive positive feedback from stakeholders and staff, there are acknowledged skill gaps in relation to some capabilities that will be required of the Commission (for example, data analytics, change management). There is not currently a formal or structured forward looking assessment to identify current or future Commission-level capability gaps on an ongoing basis. There is no formal assessment of Commission effectiveness and individual performance review for Commissioners. The Panel is of the view that even for statutory appointments a formal performance review would deliver better outcomes and accountability. |

Recommendation 7: The Government to apply a contemporary best practice merit based recruitment process to ensure fully transparent and robust appointments of the Chairperson, Deputy Chairperson and other Commissioners. Recommendation 8: ASIC to implement a periodic forward looking skills gap assessment of the Commission to identify and inform future recruitment needs. Recommendation 9: ASIC to implement a Commission effectiveness review to assess performance on an ongoing basis. Recommendation 10: ASIC to develop a formal individual performance review process for the Commissioners, led by the Chairperson. Recommendation 11: The Minister to assess the effectiveness and performance of the Commission, to be discussed with the Chairperson on an annual basis. |

|

Culture (Section 2.4) |

ASIC's culture is shaped by its stated values of Accountability, Professionalism and Teamwork, and is also a result of its origins and history. On balance, the Panel considers ASIC's internal culture to be more defensive, inward looking, risk averse and reactive than is desirable for a conduct regulator. While the Panel acknowledges that this is a broad and general observation, and there is some evidence of variability in culture within ASIC (although this is difficult to quantify), the Panel considers it to be the responsibility of leadership to set the culture and tone and to drive top-down messaging to ensure consistency. |

Recommendation 12: ASIC to initiate a review of ASIC's organisational culture and as part of that review assess the merit of implementing Google's Project Oxygen team based assessment program to inform development of Commission strategy for high performance team culture. |

|

Strategy (Chapter 3) |

||

|

Strategy development (Section 3.1) |

ASIC has a well-established strategy setting process involving both bottom-up and top-down elements. However there is some variability in the quality of the bottom-up plans. ASIC's 2015 Corporate Plan is built around a sound strategic framework and represents a major step forward in the articulation of its strategy, although there is scope for greater clarity of language. While ASIC has an established Emerging Risk Assessment process to inform its strategy development, this is not as well developed or resourced as similar functions in international peer regulators, and external inputs are not being sufficiently utilised in this process. While the identified strategic priorities (referred to by ASIC as focus areas) in the Corporate Plan are broadly comprehensive, and well aligned to international regulatory and market trends, the Panel does see a number of potential gaps related to high-priority issues in the local market context (for example, the ageing population and evolving retirement financing needs). Notably, the Corporate Plan document (as well as the underlying, non-public Business Unit Plans) is essentially silent on delivery for some important strategic priorities, including in relation to possible registry separation — not articulating how ASIC will execute on the plan over the short and medium-term. The Corporate Plan is not contributing as much as it could to ensuring accountability for ASIC's strategy execution because of the limited delivery detail (for example in the delivery of its deregulatory agenda), as well as a lack of alignment across:

|

Recommendation 13: ASIC to substantially improve the intended approach for delivery of the Corporate Plan in both the public document itself and the underlying Business Unit Plans. This should include greater specification of intended actions as well as timing, resourcing and organisational implications. Recommendation 14: ASIC to improve the selection of performance indicators to ensure that the measures associated with the Key Activities for each Focus Area are:

Recommendation 15: ASIC to review and introduce a more outcomes focused and dynamic use of advisory panels to ensure these forums input more directly into strategy development, and introduce a broader public consultation element into the strategy setting process. |

|

Strategic communication (Section 3.2) |

ASIC's communication of its mandate and strategic priorities to stakeholders does not clearly highlight its expectations about the impacts and limitations of its activities, nor does it provide clear guidance on how the strategy will be delivered. More broadly, while ASIC has a Communications Policy, it does not have a clearly-articulated strategic approach to its communications. As a result, communication does not always have a clear purpose and is at times reactive in nature (for example, focusing on responding to media and public scrutiny). ASIC could more effectively communicate what it does and why it does it, in a way that better manages the expectations gap. ASIC leadership's public articulation of its role places too heavy an emphasis on enforcement and risks driving strategic focus and staff orientation too much towards this single aspect of the regulator's toolkit. |

Recommendation 16: ASIC to further clarify and emphasise its expectations and risk tolerances (what the regulator will and will not be doing) and actively advertise and promote the strategy broadly (see Chapter 2 for further recommendations related to the SoI). Recommendation 17: ASIC to ensure the strategic framework used in developing the Corporate Plan is used consistently throughout the communications. Recommendation 18: ASIC to develop a comprehensive communications strategy that places greater emphasis on communication of the organisation's strategic priorities. Recommendation 19: ASIC to rebalance its public and internal communications about its role as an enforcement agency. |

|

Resource allocation (Section 3.3) |

ASIC's resource planning is not sufficiently flexible or responsive to changing strategic priorities. ASIC's resource allocation to enforcement is significantly greater than peer regulators. |

Recommendation 20: ASIC to ensure the top-down allocation of resources are deployed across the organisation based on the strategic priorities. |

|

Delivery (Chapter 4) |

||

|

Workforce capabilities and management (Section 4.1) |

Some ASIC staff lack sufficient professional confidence in their roles to credibly challenge regulated entities and develop and defend independent judgements The workforce also faces gaps in relation to a number of critical skill sets that will become increasingly important in the future (for example, big data, digital disruption, and behavioural economics). The existing secondment program is not being fully leveraged to close these gaps. ASIC has only relatively recently begun to develop a documented forward looking approach to organisation-wide workforce planning and has engaged external consultants to assist in developing a methodology. This process remains embryonic and has not been extended to Commission level skills gaps assessment. It is also unclear the extent to which forward-looking processes are being developed to address requirements for support functions. Public Service Act 1999 (PSA) requirements may limit ASICs ability to flexibly respond to identified gaps. |

Recommendation 21: ASIC to increase the scale and diversity of the secondment and exchange program. Recommendation 22: ASIC to improve workforce planning to include a more forward looking, strategy informed, top-down view (progressing and internalising work to date). Recommendation 23: ASIC to refresh its career value proposition to help attract and retain staff and support future secondment, by clearly articulating and tailoring messaging, and identifying strategies to deliver on this message (that is, to 'make it real'). Recommendation 24: Government to remove ASIC from the PSA as a matter of priority, to support more effective recruitment and retention strategies. |

|

Organisation structure (Section 4.2) |

ASIC's organisation structure is distinct from many peer regulators, being organised around stakeholder groups rather than by functional teams. The Panel understands the genesis and recognises the relative strengths and shortcomings of ASIC's current stakeholder based organisation structure model. ASIC is currently making progress on addressing concerns on existing silos through OneASIC and cluster specific initiatives, but could still do more to allow its people to work more flexibly across silos, to enhance cooperation, and to address risk concentrations in the most efficient and effective way. Additionally, the choice of a more expensive organisation model than the traditional model creates an imperative for an ongoing focus on efficiency and cost control at ASIC. |

Recommendation 25: ASIC to launch a pilot project to assess the suitability of dedicated project based teams to improve flexibility across units and reduce the impact of silos. Recommendation 26: ASIC to implement a regular review of internal business processes and systems, supported by improvements in MIS, to drive operational efficiency and reduce the cost burden on regulated entities. |

|

Regulatory tool kit (Section 4.3) |

ASIC has acted on prior reviews to improve the use and management of enforceable undertakings and has addressed many of the previously identified short-comings. ASIC has initiated several 'lessons learned' reviews across enforcement cases, although informed stakeholder feedback indicates this is yet to translate to material improvement. ASIC's approach to litigation sometimes lags recent progress made by other Australian regulators. For example, pleadings can be dense, complicated and lacking in focus. There is a perception that ASIC's selection of cases for litigation can be risk averse (tending to prefer cases with a higher probability of success, rather than selecting cases that have strong merits, but also allow ASIC to test the veracity of the law). ASIC's approach to collaborative partnerships (for example, co-regulation) is relatively limited and could be better leveraged to produce more robust regulatory outcomes and deliver better value for money in resource use. ASIC publishes a wide range of guidance material, and is generally proactive in its guidance approach. However in select cases, policy development and decisions lack sufficient evidencing. Further, some stakeholders feel that there is insufficient consultation during the consultation process for policy guidance development. There is an expectations gap as to the extent and rigour of merit assessment and analysis conducted in licensing and registration and therefore the extent of assurance provided to consumers and investors by these processes. The current choices around language and communication do not appear to be informed by behavioural economics (for example, the perception that 'licensing' requires ASIC to conduct due diligence to evaluate the merits of a prospective licensee). A The Panel commends the quality of ASIC's supervision, with investments in real time monitoring capabilities representing global best practice and delivering positive outcomes. Educational tools are well used, and ASIC leads international best practice in advancing broad consumer financial literacy. However, future initiatives and focus may need to be more targeted and informed by Consumer Advisory Panel (CAP) priorities and there remains potential to further leverage not-for-profits. |

Recommendation 27: ASIC to enhance enforcement effectiveness through developing a more targeted risk based approach to litigation for cases that are strategically important, and prosecutes through more focused pleadings and strategic appointment of senior counsel. Recommendation 28: ASIC to proactively develop opportunities to enhance the use of co-regulation for relevant groups of the regulated population where this will deliver superior regulatory outcomes, including through strengthened licensing and registration regimes. |

|

Stakeholder management (Section 4.4) |

While ASIC engages with regulated entities through a variety of touch points, this can be uncoordinated (particularly between stakeholder and enforcement teams and for more complex and diverse entities). Some stakeholders express dissatisfaction with the policy consultation process, particularly with regard to response time, engagement style and proportionate focus across various types of external stakeholders. External panels are not being fully leveraged and there is some inconsistency in perceived impact on strategy development. Additionally, there does not seem to be a systematic review or active and regular management of panels once created (that is, there is an element of 'set and forget' in their structure and purpose). |

Recommendation 29: ASIC to develop and implement a formal tiered stakeholder relationship model based on entity nature, scope, risk and complexity. Recommendation 30: ASIC to recalibrate advisory panel setup to ensure more systematic value add for example, through a larger pool of experts that can be called upon to advise on various issues as needed based on issue-specific needs and expertise gaps, coupled with regular performance assessment and enhanced internal responsibility to act on recommendations. |

|

Data management (Section 4.5) |

ASIC has identified a number of weaknesses in the existing data infrastructure, including fragmented databases, a reliance on legacy applications, and challenges in search functionality.

|

Recommendation 31: ASIC to execute its FAST 2 transformation program, 'future-proofing' design and expanding scope as required. Recommendation 32: ASIC to launch new programs of work to close additional identified gaps for example, to enhance the ability to measure and report for MIS.

|

Report roadmap

The report is structured across five key chapters:

- Chapter 1: Context and approach — provides an overview of the objectives and methodology of the Review, an overview of ASIC and a discussion around the external environmental factors impacting ASIC's future capability requirements and strategic focus areas.

- Chapter 2: Governance and leadership matter most — provides an assessment of the key findings and recommendations across four aspects of governance and leadership that matter most in setting the future direction of ASIC — external governance, internal governance, leadership talent and culture.

- Chapter 3: Strategy — critical for a shared focus and understanding of what matters — provides an assessment of the key findings and recommendations across three aspects related to ASIC's strategy capabilities — strategy development, strategic communication, and resource allocation.

- Chapter 4: Delivery to be enhanced with 'future-proofing' design — provides an assessment of the key findings and recommendations across five aspects of delivery — workforce management, organisation structure, regulatory toolkit, stakeholder management, and data management.

- Chapter 5: External constraints that impede ability to execute — discusses exogenous factors (outside of ASIC's control) that will impact ASIC's ability both to respond to the recommendations made in this report, and on its ongoing and future ability to fulfil its mandate efficiently and effectively.

In addition, the Report has five Appendices:

- Appendix A: Provides a detailed implementation plan for proposed recommendations.

- Appendix B: Provides an illustrative benchmark Statement of Expectations.

- Appendix C: Glossary of terms used throughout the report.

- Appendix D: A list of external organisations and individual stakeholders consulted with over the course of the Review.

- Appendix E: A copy of ASIC's formal response to the Capability Review (provided to the Panel post completion of the Report).

1 Susan Bell Research 2015, ASIC Capability Review: Comparing the views of ASIC's leadership team with the views of external stakeholders, in Appendix E of Evidence Report — Volume 3, pages 64-91.

2 Susan Bell Research 2015, ASIC Capability Review: Comparing the views of ASIC's leadership team with the views of external stakeholders, in Appendix E of Evidence Report — Volume 3, pages 64-91.

3 PwC 2015, ASIC Capability Review: Evidence Report — Volume 1, Sydney, page 20. ASIC Commissioners spend an average of 21 per cent of their time on meeting/engagement activities with external stakeholders.

4 PwC 2015, ASIC Capability Review: E

vidence Report — Volume 1, Sydney, ibid.

5 Analysis conducted by ASIC based on review of Commissioners' diaries and reflection on activities between September and November 2015. Given some Commissioners' leave and travel arrangements during this time, note that analysis was conducted to reflect a one month long period when they were present in the office. Analysis assumes a 9 hour day and 22 working days a month.

6 Ibid.

7 Burgess, V 2015 (November 18), 'Risk aversion still chokes up the public service', Australian Financial Review.

8 IOSCO 2010, Objectives and Principles of Securities Regulation.

9 PwC 2015, ASIC Capability Review: Evidence Report — Volume 1, Sydney, page 87.