A good tax system raises the revenue needed to finance government activities without imposing unnecessary costs on the economy. Tax reform is about how revenue is raised, not just about how much.

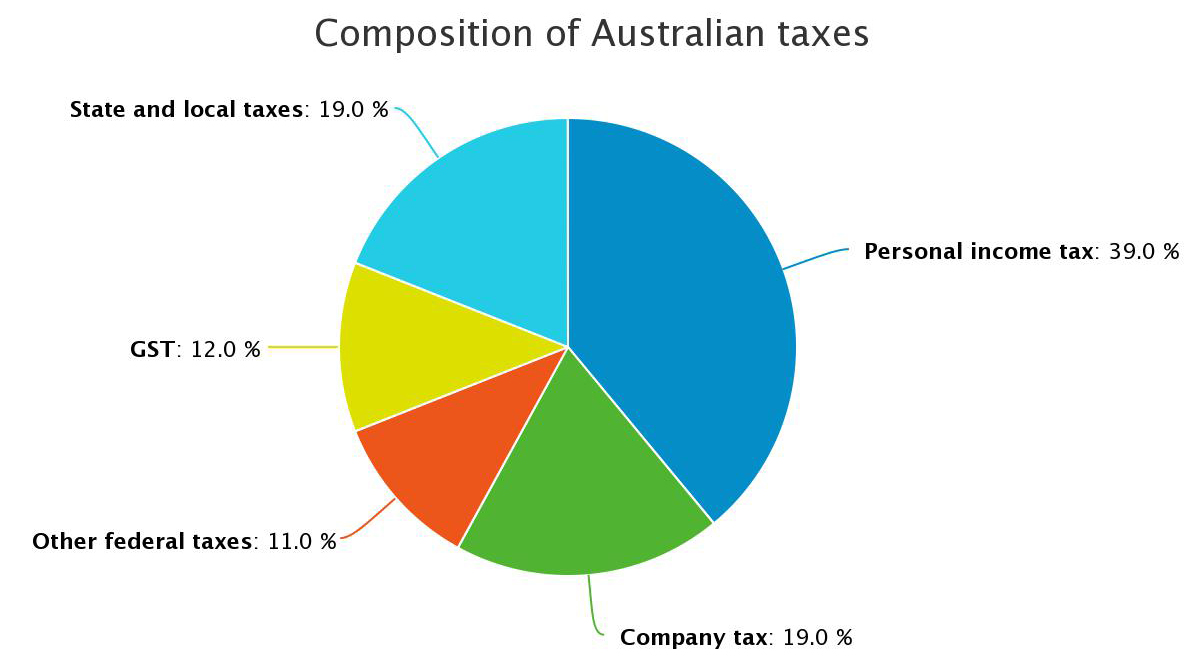

Australia’s overall tax burden is relatively low compared with other developed countries and regional competitors. The federal Government raises around 81 per cent of total tax revenue in Australia. State and Territory governments receive 45 per cent of their revenue through transfers from the federal Government, including all GST revenue.

Note: Percentages may not sum up to 100 per cent due to rounding.

Source: ABS, Taxation Revenue, 2012-13.

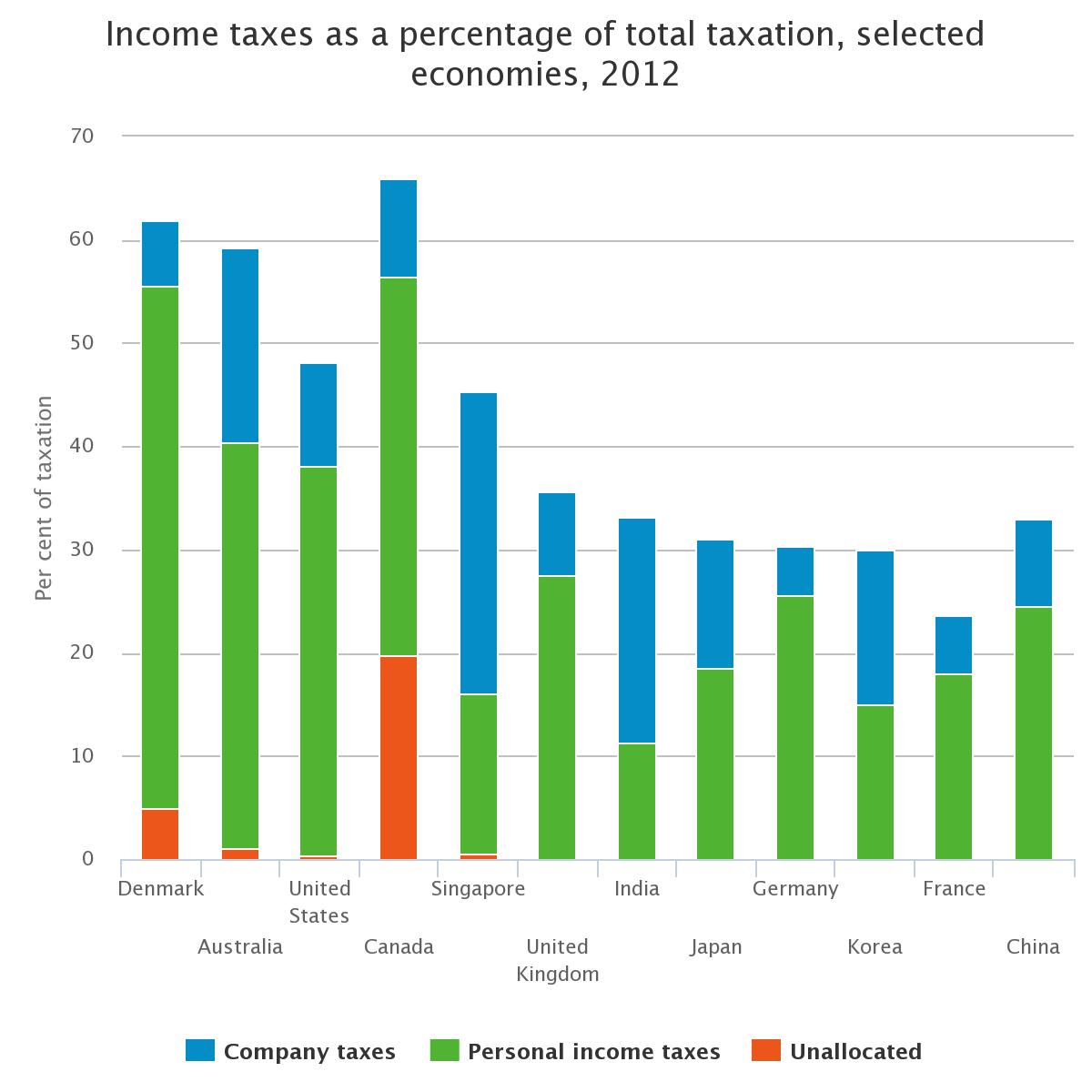

Australia relies heavily on individuals’ and corporate income taxes compared with other developed countries, as well as some regional competitors. Australia’s reliance on individuals and corporate income taxes remains much the same as it was in the 1950s, despite the significant change to the economy. This reliance is projected to increase further, largely due to wages growth and individuals paying higher average rates of tax (bracket creep).

Note: Income taxes do not include payroll tax or social security contributions. Statistics for non-OECD and OECD countries may not be directly comparable

Source: OECD, Revenue Statistics; Treasury estimates using IMF, Government Finance Statistics, and Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy database.

Economic modelling shows that company tax and stamp duties in particular affect economic growth. The entire economy benefits from reducing the economic costs of taxation, including workers through higher wages.

Much of the burden of Australia’s high company tax rate is expected to fall on Australian workers. This is because, over time, the amount of capital investment in Australia (for example, the construction of buildings and purchase of equipment for production) is affected by the company tax rate. Lower amounts of capital investment in the Australian economy will reduce the output or productivity of workers and, in turn, reduce the real wages of employees.

A growing problem is the increased complexity and compliance costs in the tax system. Tax compliance costs are in the order of $40 billion per year. Reducing complexity requires change to tax design and governance practices.

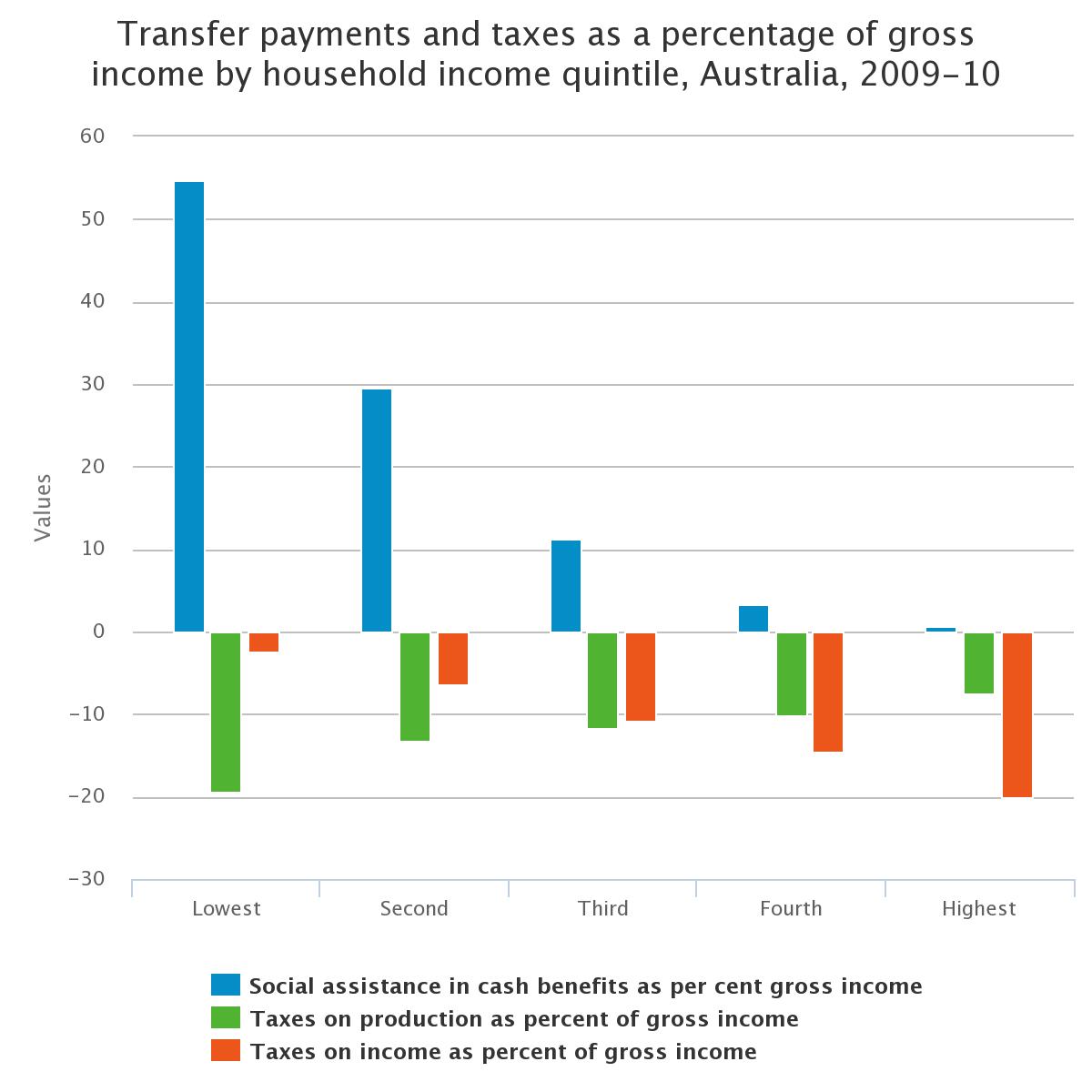

Australia’s tax and transfer systems are highly progressive, which supports fairness. High effective tax rates, including as a result of targeting in the transfer system, can reduce participation incentives for some groups. Bracket creep exacerbates this problem.

Tax settings for savings should give people the incentive to save for their future, but differences in the taxation of alternative savings vehicles affects savings choices.

Individuals income tax

Individuals’ income tax is the single most important source of government revenue. Since the mid 1970s it has consistently raised around half of the Australian Government’s tax receipts and continues to be a stable and predictable source of revenue.

Australia’s individuals income tax schedule is progressive , with a high tax-free threshold followed by increasing tax rates at subsequent thresholds. This means that the largest amounts of income tax are paid by high income individuals. In 2011-12, around 2 per cent of individuals had taxable income above the $180,000 threshold and collectively paid around 26 per cent of total individuals’ income tax.

For many people, individuals’ income tax does not significantly alter their workforce participation. However, it can be more distorting for particular groups of taxpayers, such as low income earners or the second income earner in a family, or high income earners with the ability to plan their tax affairs.

The progressivity of the tax and transfer systems

Australia’s tax and transfer systems are highly progressive. Progressive individuals tax rates and thresholds underpin the overall progressivity of the tax system.

Note: Production taxes capture payroll taxes, stamp duties and land tax incurred through business production, but not taxes on profits or other income (e.g. company income tax).

Source: ABS, Government benefits, taxes and household income

Australia’s individuals’ income tax regime is very progressive compared with other countries. Australia has relatively low average and marginal tax rates at low income levels, but relatively high marginal tax rates at high income levels.

Many other countries levy a social security contribution on employee earnings, with the same flat rate applied to everyone. These ‘contributions’ are notionally allocated to pay for unemployment and aged care allowances over a person’s lifetime. As a flat rate tax, social security contributions have a greater impact on low income earners and their discretionary spending options.

Australia does not apply a separate social security contribution. Pension costs are funded from Australia’s main revenue stream and supplemented by the private superannuation system.

A trade-off for Australia’s low average individuals’ tax burden is that the statutory and effective tax rates, produced by the interaction between the tax system and tightly targeted transfer system, are comparatively high by international standards.

For example, a single person in New Zealand earning NZ$40,000 a year would pay 18.95 cents in tax on their next dollar of income and pay annual tax of NZ$6,6001. In Australia, a single person earning A$40,000 a year would pay 36 cents in tax on their next dollar of income and pay annual tax of A$4,9472.

Bracket creep

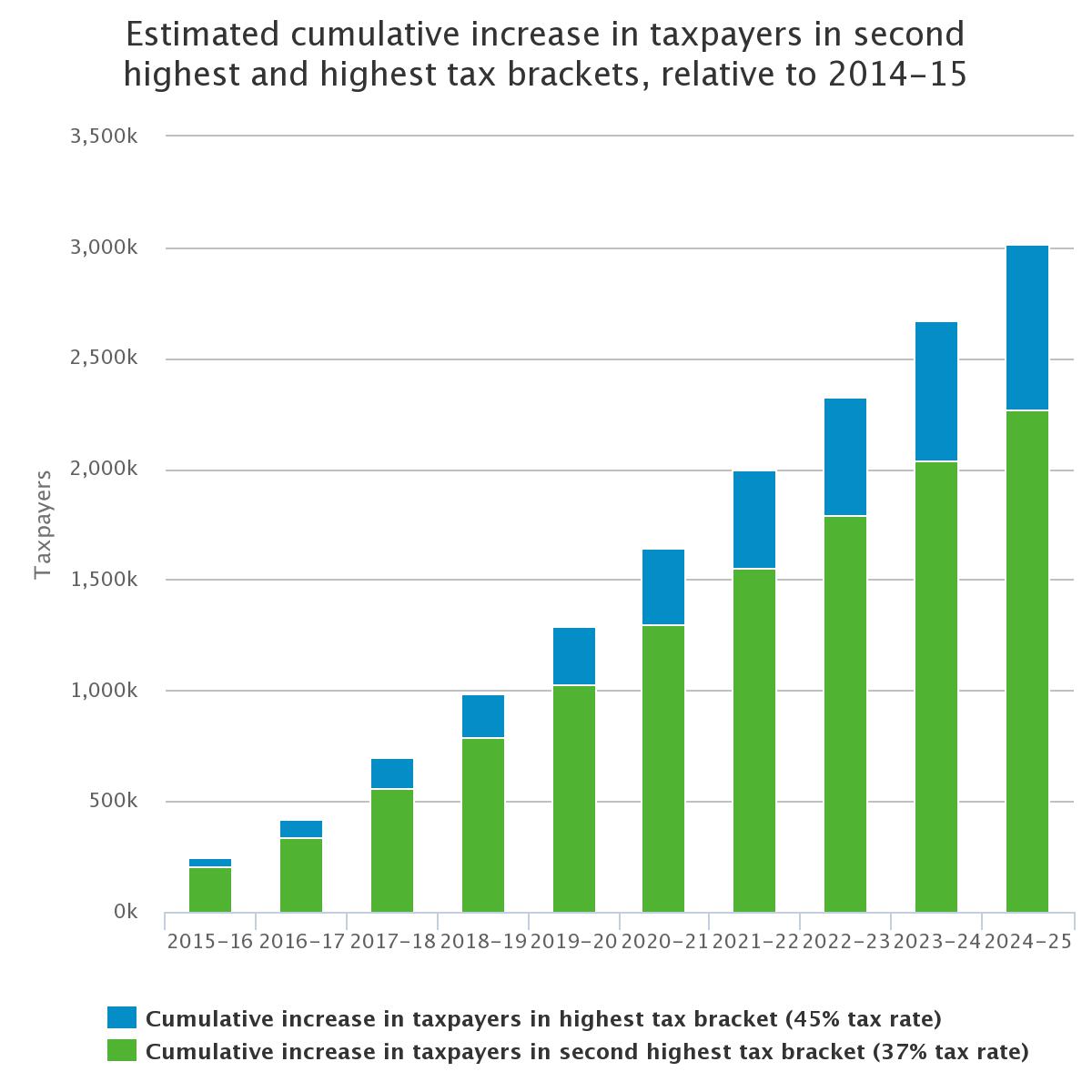

Progressivity in the individuals’ income tax system is delivered by applying higher rates of tax above different income thresholds. These thresholds do not automatically keep pace with inflation or wages growth.

Bracket creep (also called ‘fiscal drag’) is where a higher tax rate applies to a taxpayer, as their income increases over time, but tax thresholds are held steady. Bracket creep reduces the progressivity of the individuals income tax scales over time. This is because the tax increase for individuals with lower incomes is greater as a proportion of their income than for those at higher incomes.

For some people, particularly those on relatively low incomes, bracket creep may reduce incentives to work. At higher incomes, bracket creep increases the incentives for tax planning and structuring, and even overseas relocation. Bracket creep diminishes progressivity, and exacerbates the other problems in the individuals income tax system, such as reward for effort and incentives for tax planning, over time.

Tax on savings

Australia’s current tax system taxes savings differently depending on the form of the saving. As a result more savings are held in superannuation and housing than would otherwise be the case.

The effect of the tax system on the aggregate level of domestic savings is uncertain. The effect of tax on domestic savings is unlikely to significantly affect the aggregate level of investment in Australia (which is determined largely by the decisions of foreign investors). This suggests that taxing income from savings (at least to a point) is a relatively efficient way of raising revenue. However, some level of concessional tax treatment for savings may be warranted to reduce any disincentives to save.

Taxing savings income also has distributional effects, in part because higher income individuals have a greater capability to save in lower taxed savings vehicles. However, distributional judgments must take into account the full amount of any income support received, such as the Age Pension.

Business tax

Tax is increasingly important as competition for foreign investment intensifies and businesses become more mobile. Australia’s corporate tax rate is high compared with many of Australia’s competitors, especially in the Asia-Pacific region.

While company tax is paid by companies, the burden is passed on to shareholders, consumers and employees. A more competitive business tax environment would encourage higher levels of investment in Australia and benefit all Australians through increased employment and wages in the long run.

Dividend imputation ensures there is no double taxation on income from Australian shares owned by Australian resident shareholders and supports the integrity of the business tax system. However, it makes little contribution to attracting foreign investment to Australia other than eliminating dividend withholding tax for franked dividends paid to foreign shareholders. It also involves a significant cost to revenue and may impose more compliance costs to achieve similar outcomes to other jurisdictions.

Australia’s corporate tax system is also extremely complex. Artificial distinctions embedded in the system often create unintended biases towards particular forms of investment, distort business decisions and increase incentives to engage in complex tax planning.

Business innovation encompasses improvements to goods and services, processes and marketing. Benefits can include productivity enhancements, firm growth, job creation and higher living standards. The research and development tax incentive and employee share schemes are two ways that the tax system supports business innovation.

Small business

Australian small businesses are numerous, diverse, and make an important contribution to the Australian economy. These businesses adopt different legal and management structures, and may be driven by different preferences and profit motives than larger businesses.

Navigating a complex tax system is disproportionately burdensome for small businesses, especially as certain features of the system can encourage them to adopt particular legal structures that are costly to establish and maintain.

The tax law provides a number of concessions intended to benefit small businesses, but these may add to the complexity and compliance burden for small businesses.

Not-for-profit sector

The not for profit (NFP) sector is large and diverse and provides important benefits for the Australian community.

Governments provide a number of tax concessions to support the NFP sector. While these tax concessions help increase the level of activity in the NFP sector, the value of revenue forgone from the concessions is significant and growing steadily.

Tax concessions for the sector can also increase complexity, in part because they vary according to the type and purpose of NFP organisations. In some cases, NFP tax concessions provide NFPs with a competitive advantage over their commercial competitors.

The GST and state taxes

As with most federations around the world, State and Territory governments in Australia (including local governments) spend more than they raise in revenue. The difference is made up by grants from the Australian Government.

The States and Territories receive all revenue raised by the GST. About 23 per cent of total state revenue comes from the GST, with state‑levied taxes generating about 31 per cent of total state revenue. The GST is relatively efficient compared to some other taxes because it has a much broader base than many other taxes. However, exemptions reduce its efficiency and introduce significant complexity. In total, around 47 per cent of Australia’s national consumption is subject to GST.

Legislation requires that changes to the GST base or rate require unanimous agreement by all State and Territory governments, as well as both houses of the Australian Parliament. The Australian Government will not support changes to the GST without a broad political consensus for change, including agreement by all State and Territory governments.

The major sources of state tax revenue are payroll taxes and stamp duties. State governments also impose taxes on land, gambling and motor vehicles. Municipal rates are the sole source of local government tax revenue.

Some studies suggest significant economic gains from state tax reform, particularly reduced stamp duties and greater use of payroll and land taxes.

Indirect taxes

Indirect taxes on specific goods and services can be an efficient way to raise revenue. However, an ad hoc approach has contributed to a range of complexities and inconsistencies.

Fuel taxes are the largest source of revenue from a specific good or service.

Taxation of alcohol has two separate regimes, a value based tax for wine products and a volume based excise tax for other alcoholic beverages, with 16 different excise categories.

The Luxury Car Tax has a narrow tax base, is complex and is the Australian Government’s only luxury tax on a specific good or service.

Complexity

The complexity of the Australian tax system reduces integrity and transparency, and imposes unnecessary compliance costs on taxpayers, as well as other costs on the Australian economy.

The complexity largely reflects the historical foundations of the tax system and the way changes to the system have been implemented in the past. This makes it difficult to address without broad community support.

Tax administration is increasingly important to minimise the impact of tax system complexity and to make it easier for taxpayers to comply with their obligations.

Establishing a metric to measure tax complexity could assist in managing the complexity of the tax system.

Governance

Governance institutions and arrangements apply across the tax system, including at the policy design, legislative, administrative, and appeals stages.

In Australia, decisions on tax policy are made by the Government and the Parliament, with formal policy advice provided by the Treasury, in consultation with the ATO. Further advice is provided by many different groups, including tax practitioners, industry groups, think tanks, the public and the media.

A range of possible reforms to tax system governance could be considered to increase certainty, improve consultation processes and enhance public understanding of tax policy and administration.

1. Includes Accident Compensation Corporation earner’s levy.

2. Includes Medicare levy and low-income tax offset.