Thank you for the opportunity to address you today on taxation reform.

I'd like to extend my thanks to the convenors of this colloquium, Dr Tom Karmel and others from the Economic Society of Australia, for this invitation to speak to you today.

The Tax Review Panel of which I am chair is now more than a year into the Australia's Future Tax System review. The Prime Minister and the Treasurer have described it as 'root and branch' — the most comprehensive review of the Australian taxation and transfer system, including state taxes, for at least the last 50 years.

One of the more prominent parts of this ever growing plant, with its sprawling limbs, runners and branches, is the taxation of the personal capital income of Australians — broadly understood as income from 'saving'.

I have made a number of speeches on a range of issues associated with the tax review, but the tax treatment of savings is not something I have directly addressed. I would like to take the opportunity today to do so.

And this is a timely opportunity. The global financial crisis serves as a reminder that countries, like Australia, with high rates of domestic investment cannot take for granted that it will always be financed by a perfectly elastic supply of foreign saving to supplement domestic savings. The level of domestic savings matters. The composition of domestic savings may also matter. This is particularly the case if there are significant externalities involved in domestic saving being in a form that can adjust quickly to shifts in foreign capital flows.

One piece of anecdotal evidence that has captured my attention in the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis is the role played by Australian superannuation funds in financing, through equity purchases, a large-scale de-leveraging of corporate Australia. It is not at all clear that such a large structural change in corporate financing could have been achieved without our very substantial pool of superannuation savings.

Another consideration worth thinking about is that while domestic investment can be financed either by domestic saving or the saving of foreigners, the future living standards of today's working Australians will have more to do with the returns generated by the former — that is, the returns on their own savings. As the Australian population ages, the quality of our domestic saving decisions is going to become increasingly important.

Personal capital income taxes are taxes on saving. They affect how consumption is distributed over a person's lifetime and, in turn, the national level of saving. Further, the personal capital income tax settings have other effects. Taxing savings reduces the gains from working, where some of those gains are saved. It affects the allocation of a household's savings among various assets as well as having important implications for equity.

Comprehensive income taxation — three initial observations

In Australia, personal capital income taxation policy, and tax policy more broadly, has long been inspired by the ideal of comprehensive income taxation. Typically this has involved a concern with nominal, rather than real or inflation-adjusted, income.

The theoretical premise behind our version of this inspiration is quite elegant in its appearance and relatively simple in its logic: a dollar of income is a dollar of income, so it should be taxed at the same rates regardless of how it is derived. All income should be treated the same whether it comes from a bank account, shares, property or paid work.

At face value, this argument is compelling. Proponents of comprehensive income tax argue that it is unfair that things like capital gains are taxed less than paid work: it should all be treated as taxable income. If someone earns $100,000 from capital gains or interest income, and someone earns $100,000 from work, they should be taxed at the same rate.

Allow me to make three initial observations.

My first observation is self-evident to most economists. The example I just described looked at comprehensive nominal income, rather than real income, as it included both inflationary gains as well as actual increases in economic power (or real gains).

Consider the following example. If you purchase an asset for $100 and sell it a year later for $106 — earning a 6 per cent return — the full return ($6) is subject to tax. If inflation was also 6 per cent then the real return is zero. The same bundle of goods that cost $100 last year would cost $106 this year. So by being taxed on the inflationary return you are no longer able to consume the same bundle of goods in the future that you could consume today.

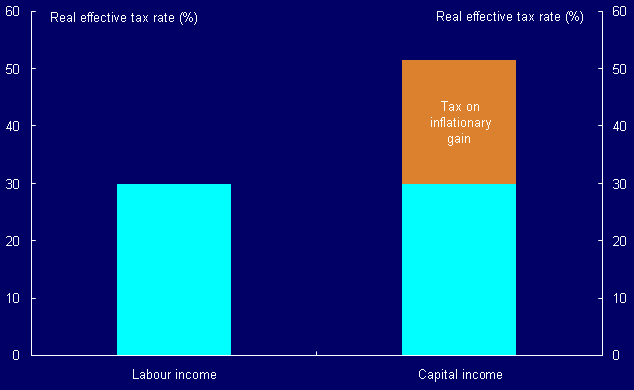

We can see this from the first chart (Chart 1). Consider a taxpayer who faces a statutory tax rate of 30 per cent for both their labour income and their income yielded from an asset (say an interest income stream). The effective tax rate on labour income consumed today is a neat 30 per cent; the column on the left.

Chart 1: Taxing the Infationary Gain

On the other hand, the column on the right represents the effective tax rate on the income from the asset. Had inflation been zero, the effective tax rate on the income from the asset would also have been the 30 per cent statutory rate. However, even under low rates of inflation, the real effective tax rate on capital income can be much higher than the statutory tax rate. Assuming a nominal return of 6 per cent per annum and 2.5 per cent inflation, the real effective tax rate would be around 51 per cent, two-thirds higher than the statutory tax rate.

Comprehensive nominal income taxation does not actually treat labour and capital income the same. For them to be treated the same, an adjustment for inflation is needed.

The second observation to note is that whenever we consider the taxation of personal capital income, the effect of means testing government benefits needs to be taken into account. While means tests and income taxes have a different administrative basis, they can have similar economic impacts.

The withdrawal of benefits can lead to disincentives to work and the same logic extends to savings. Empirical research bears this out, showing that means testing affects decisions to work and save1.

So the tax and transfer systems impose taxes on savings, be it through capital gains tax, income tax, an assets test or an income test. How these two systems fit together is something the Panel has been considering carefully.

My third observation is that while many in Australia continue to see comprehensive income tax as the ideal, seminal reviews into taxation around the world in the last three decades have largely gone the other way. These reviews, carried out by leading public finance economists, have abandoned even the comprehensive real income ideal, let alone comprehensive nominal income. The US Treasury Blueprints for Basic Tax Reform in 1977 and the Meade Committee Review in the United Kingdom in 1978 are examples. Based on their publications to date, the current Mirrlees Review being conducted by the UK Institute of Fiscal Studies appears likely to follow this trend.

The fact is that comprehensive income taxation has, for some time, been considered by many economists as 'old thinking'. Looking at the recent work in this area, there are arguments for taxing savings at a higher rate than labour, arguments for taxing savings at a lower rate than labour, arguments for subsidising saving and there are even arguments for taxing savings at age‑dependent rates. However, as Professor Auerbach from Berkeley pointed out at the AFTS conference in Melbourne in June, he was not aware of any rece

nt credible work that would suggest that taxing capital income at the same rate as labour is optimal, other than for administrative reasons.

Notwithstanding the declining theoretical support for comprehensive income taxation, many of the major reform exercises in Australia in the last three decades, inspired by the Asprey Taxation Review in the 1970s, have involved trying to move the legal tax base closer to comprehensive income. And I would argue that these reforms have, generally, been highly beneficial.

Before I further discuss some of the broad policy choices, it is worth reflecting on how the personal capital income tax system in Australia has evolved and what it is today. Doing so will give context to a discussion of the competing benchmarks.

Past changes

Prior to Asprey, the tax laws recognised many items that were in an economist's definition of nominal capital income: profits from a business, interest, rent, dividends and other periodic receipts. These were generally included in the calculation of taxable income and taxed at the same progressive rates as labour income.

Items that were not recognised back then, or only brought into the tax base to a limited extent, included: fringe benefits, capital gains, superannuation earnings, retirement lump sum benefits, imputed rent from owner‑occupied housing and consumer durables, bequests and gifts received. Of these untaxed or lightly taxed items, it has been in the areas of capital gains and superannuation where most changes in the taxation of savings have occurred since Asprey.

Capital gains became generally taxed through the capital gains tax provisions from 1985. Inflation adjustments were provided so that what was taxable was more like real income — but on a realisation basis. It was, of course, recognised that capital gains were still being treated more favourably than some other forms of capital income, such as interest income, because of the inflation adjustment and the deferral of taxation to realisation.

Capital gains indexation lasted 15 years. The Review of Business Taxation, chaired by Mr John Ralph, proposed the abolition of capital gains indexation and averaging to be replaced by a capital gains tax discount. As a result, and subject to certain conditions, individuals today include only 50 per cent of the realised nominal capital gain from assets in their taxable income. Superannuation funds were afforded a capital gains tax discount of one‑third of the realised nominal gain.

A second area of significant reform was the taxation of superannuation. Prior to 1988, superannuation pensions were treated largely on a post-paid expenditure tax basis — close to what is often called a 'big E, big E, big T', or EET, treatment. That is, contributions into superannuation funds were exempt (the first 'E'), the fund earnings were exempt (the second 'E') while retirement benefits were pretty much fully taxed (the 'big T' at the end, although lump sum benefits were taxed as a 'little t').

Since then, the tax burden has been shifted away from the taxation of retirement benefits, with taxes being applied at the contributions and earnings level, but generally at concessional rates.

Under current arrangements, superannuation benefits paid from a taxed source are tax‑exempt when paid to a person over sixty. Contributions are subject to a 15 per cent contributions tax and earnings in the fund are also taxed at a 15 per cent statutory rate. However, the average effective tax rate on earnings, based on tax revenue collected as a proportion of pre‑tax fund earnings, is more like 7-8 per cent because of the capital gains tax discount and refundable imputation credits. Focussing on the effective rate rather than the statutory rate makes sense to the extent that an imputation credit to resident shareholders is a refund for a tax that they, given that Australia is an open economy, have not entirely borne.

The current treatment can be described as 'little t, little t, big E'. Contributions are taxed at a low rate (the first 'little t'), as are fund earnings (the second 'little t') while benefits withdrawn at retirement after age 60 are exempt (the 'big E' at the end).

That said, the first 'little t' can be misleading — especially when compared to other forms of saving. Unlike a bank account, the individual is effectively getting a deduction for saving into superannuation at their marginal tax rate — which, for higher marginal tax rate individuals is then only partially corrected by the 15 per cent contributions tax. Access to a partial deduction for saving (or access to co-contributions), the very low rate of tax on earnings and the exemption of retirement benefits mean that, for many individuals, especially those on top marginal tax rates, saving into superannuation is afforded a better‑than‑expenditure tax treatment.

The overall picture today

So, how far has the inspiration of comprehensive nominal income taxation got us and what is the shape of the current treatment of capital income?

For personal capital income, the answer to that question is 'not very far and not very consistently'. Our income tax system resembles an ad hoc dual income tax — where capital income is generally treated separately and concessionally. However, unlike what may be considered a pure dual income tax model, different savings types are treated at a variety of different effective tax rates.

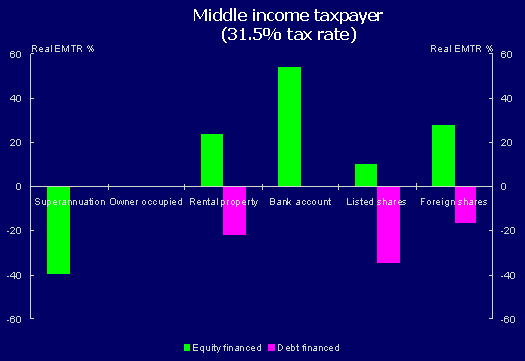

Consider the following chart (Chart 2), which estimates forward‑looking real effective marginal tax rates on hypothetical saving, in assets commonly owned by middle income taxpayers. The real effective marginal tax rates show the tax levied on the normal return to saving, which is made out of after-tax labour income. A zero effective tax rate represents the (pre-paid) expenditure tax treatment.

Chart 2: Different Treatment of Savings Types

As mentioned earlier, concessional superannuation is treated more favourably than the expenditure tax benchmark. This yields a large negative effective tax rate. Note that these calculations ignore the effect of means tests. The tax imposed on retirement through means testing would, if factored in, have the effect of increasing these effective tax rates.

For interest bearing deposits, the real effective tax rate is well above the taxpayer's 31.5 per cent statutory rate (around 50 per cent) as the entire real and inflationary gain is included in taxable income. This is consistent with comprehensive nominal income taxation.

Ignoring local property levies, whose incidence is most probably capitalised into property values, owner-occupied housing is outside the capital income tax base and faces a zero effective tax rate.

Rental properties, however, face different effective tax rates depending on the financing choice of the saver — a low positive effective tax rate when equity financed but a negative effective tax rate when geared. The tax treatment of a negatively geared property would typically involve the taxation of rental income and the deduction of interest and other expenses at the full personal marginal rate, with capital gains taxed at a half rate due to the capital gains tax discount. This throws up a significant asymmetry.

The same result applies for other types of geared investments that yield capital gains. The treatment of foreign shares, or shares in Australian companies that invest offshore, have similar characteristics to the treatment of rental property in that capital gains are afforded the discount.

Listed shares in companies with domestic investments are eligible for imputation credits on top of the capital gains tax discount. Thus, the effec

tive tax rate for franked dividends is lower than for dividends from foreign shares.

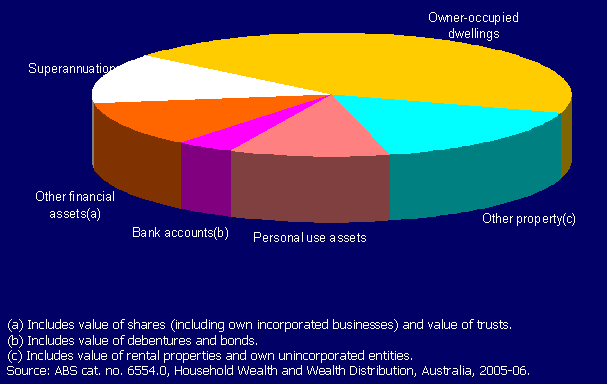

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, as shown by the chart on-screen (Chart 3), the principal holdings of Australian households are:

- their own home (44 per cent of household assets) which is untaxed through the income tax system;

- other property — including rental property (16 per cent) which is lightly taxed;

- superannuation (13 per cent) which is at most lightly taxed;

- shares and interests in trusts (12 per cent) (labelled 'other financial assets' in the chart) which are lightly to moderately taxed;

- personal use assets (11 per cent) which are untaxed; and

- bank accounts and bonds (4 per cent) which are fully taxed at marginal rates.

Chart 3: Composition of Household Assets

Clearly we have a savings tax base that exempts the lion's share of savings (owner-occupied property, personal use assets), fully taxes a very small proportion of savings (returns from interest‑bearing deposits), and lightly to moderately taxes everything else at varying rates.

Superannuation is affected by the Superannuation Guarantee. But voluntary contributions are also large. It seems plausible, then, that the particular allocation of household savings among various assets has something to do with the tax system. And we might well enquire whether that particular allocation of savings - and the particular tax system applying to them - is in any sense optimal.

Is this the way in which the various forms of domestic saving should be taxed if we are to deal effectively with the looming economic, social and environmental challenges associated with population ageing and the probability of persisting, for many years into the future, with one of the highest rates of investment - in plant, capital equipment and infrastructure - in the developed world?

Policy considerations

Would it be better to continue with the ideal of comprehensive income taxation that has had so much influence in Australian tax policy up until now, or to opt for an expenditure tax approach?

This takes us back to my third initial observation, that the logic of income from all sources — even disregarding inflationary gains — being subject to a common progressive tax schedule is now widely accepted to be flawed.

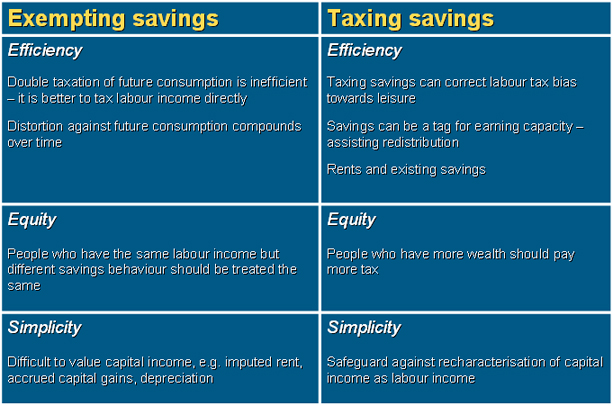

Consider the following table (Table 1).

Table 1: Arguments for Each Base

If we consider savings as deferred consumption — that is, consumption at different dates like the consumption of different goods — taxing future consumption at higher rates has important implications. Economic theory in this area, based on the work by Sir Anthony Atkinson and Joseph Stiglitz in the 1970s, suggests that if the labour income tax schedule is chosen optimally, then under fairly reasonable conditions social welfare cannot be improved by taxing commodities differently. Therefore social welfare can not be improved by taxing current and future consumption differently, if wellbeing is based on a lifetime as opposed to annual perspective.

This result is more compelling the more you look out into the future. If you impose a 30 per cent tax on the returns to both work and saving, the effective tax rate on consumption if you consume immediately is 30 per cent. But, even when inflation is ignored, the tax on real capital income not only distorts current and future consumption, but distorts consumption more and more as it is deferred further into the future — as the tax on earnings has a compounding effect over time. If you defer consumption for 10 years the effective tax rate rises to around 40 per cent. If you defer consumption for 20 years, it rises to around 50 per cent. When inflation is taken into account, the compounding effect of the tax rates is, of course, even more extreme.

So, even if it were optimal to tax future consumption at a higher rate than current consumption, it is unlikely that it would be efficient to tax future consumption at higher and higher rates the longer it is deferred. The comprehensive income tax discriminates against taxpayers who save in the earlier stages of life, with those individuals paying a higher lifetime tax bill than people with similar earnings who choose to save less2.

Further, there are practical difficulties in valuing and assessing economic income, even for things like business profits, let alone items such as unrealised capital gains and imputed rent. So achieving uniform taxation of all forms of nominal capital income is problematic, to say the least.

The only coherent reason for taxing on a nominal income basis is that treating labour and capital income at different statutory rates can lead to administrative difficulties in addressing the incentive to recharacterise labour income as capital. There is much in this practical argument. However, under current tax arrangements, we already face it.

Unfortunately, while the case for comprehensive income taxation is flawed, the case for adopting an expenditure tax is also far from watertight. Even from a theoretical perspective, there are a number of arguments suggesting that a positive tax rate on the normal return to saving may be part of an optimal tax system.

The Atkinson-Stiglitz result assumes that the labour income tax schedule has been selected optimally and that present and future consumption are equally substitutable for leisure. But when this schedule is not optimal, a tax on saving may, depending upon the complementarity of leisure and future consumption, also offset the negative impacts on labour supply arising from the labour income tax.

Also, individuals with more education tend to have higher savings rates than people with less education. If the level of education is a signal for innate ability (or earnings capacity) then a tax on savings will tend to fall disproportionately on more able individuals. It is argued that this will assist the government to redistribute income from high ability to low ability individuals in a less distortionary manner.

There are also transitional and design issues. An expenditure tax would tax consumption from existing wealth while only providing a deduction for new saving.

If, instead, an expenditure tax were to be implemented by simply exempting capital income from tax, existing wealth would be afforded a positive windfall. Further, supernormal returns, which do not affect savings decisions, would also become tax exempt. And exempting capital income would come at an efficiency cost since it would have to be funded by raising distortionary taxes elsewhere.

What I have just discussed are arguments concerning efficiency. Unsurprisingly, the equity arguments are even more heated.

Advocates for comprehensive income argue that capacity to pay is reflective of the amount by which an individual's ability to purchase goods and services has increased in a given period. So the income benchmark is the incremental increase in the undiscounted value of lifetime consumption.

By contrast, expenditure benchmark proponents argue that the amount of tax an individual should pay in a given period should be based on the incremental increase in discounted lifetime consumption possibilities. Normal returns to saving do not increase consumption possibilities — they merely reflect compensation for consumption deferral. Returns to labour (and economic rents) do, however, represent an increase in consumption power, whether they are consumed now or later.

To put it more in

tuitively, the income benchmark argues that 'people who have more wealth should pay more tax' while the expenditure benchmark argues that 'people who save more than others of the same labour income shouldn't pay more tax'. These equity considerations are quite contentious and can be argued either way.

So what should we make of all this? There is probably no clear cut answer that allows us to pick one benchmark over another. We are in a more complicated, less certain, world of trying to find a more efficient and fairer balance in the taxation of savings, including taking account of interactions with the transfer system.

Conclusion

Let me sum up.

We have a system for taxing personal capital income that has evolved into something that is, to put it mildly, far from the originally intended ideal.

Further, the case for staying true to that original ideal now appears weak; while the case for moving to the other conceptual ideal is not strong either.

Meanwhile, we have a tax system for household saving that has not been calibrated to address the challenges of population ageing and the financing of unprecedented levels of business investment and infrastructure.

While we can see that we have a system that is ripe for reform, we can also see a complex set of tradeoffs in respect of the choice of the savings base, the choice of rate and the forms in which such a tax might be levied. Judgement is required.

Over the next couple of months, we will be refining our judgements on these important issues as we finalise our report on the tax and transfer system. Thank you for your interest.

1 See for example Piggott, Robalino and Jimenez-Martin (2008) Incentive Effects of Retirement Income Transfers; Meghir and Phillips (2008) Labour Supply and Taxes.

2 Judd, Kenneth (1985), Redistributive taxation in a simple perfect foresight model; Chamley, Christophe (1986) Optimal Taxation of Capital Income in General Equilibrium with Infinite Lives

The speech was originally posted on the Australia's Future Tax System website.