Downloads

Introduction

My subject today is the role of fiscal policy - a topic that not so long ago was a little unfashionable.

Today, the topic is generating a level of debate that we have seen on only a handful of occasions in the past fifty years.

It is not that long ago that monetary policy was the macroeconomic stabilisation tool of choice and fiscal policy was about the medium term and allowing the so-called automatic stabilisers to work. Discretionary fiscal policy was frowned upon, because it was seen to be too slow, too clumsy or too political. In more extreme views, it simply was not relevant from the point of view of economic theory.

I do not want to revisit this history this morning. But it seems reasonable to claim that developments in the global economy over the past couple of decades have led to a new view 1.

That view is that discretionary fiscal policy can play a useful role in supplementing monetary policy in the face of a prolonged slowdown. The case for discretionary fiscal policy action is stronger the more foreseeable and severe the slowdown. Fiscal policy is also useful the more financial the shock that causes the slowdown and the closer short-term interest rates are to the 'zero bound'.

The actions currently being taken by governments around the world are likely to enhance economists' understanding of the appropriate role for fiscal policy and how to implement a fiscal expansion.

While it is too early to tell, it seems that, while monetary policy will remain the primary tool for macroeconomic management, fiscal policy is likely to remain a little more fashionable than it has been.

Context: the global financial crisis

The context to the current discussion around fiscal policy is important. You should be wary of economists bearing forecasts, but let me give you the prediction that I will not be the last person to mention the global financial crisis today.

The global financial crisis probably represents the most significant disruption to the world economy that any of us has seen in our adult lives. Its genesis is yet to be fully documented, but let me try to give you a summary.

A significant flow of capital earlier this decade from high-saving East Asian economies to developed economies in North America and Europe caused significant declines in real risk-free rates of interest. Very low interest rates drove an expansion of credit and a search for yield. Sharp increases in asset prices and growth in securitised credit were the result, especially in the United States.

After some time, the lending positions and inflated asset prices necessarily began to unwind, bringing a large amount of pressure to bear on the books of many financial institutions. Credit markets began to seize up more generally as a result, and there was an inevitable feedback to real economic activity.

This summary is, of course, quite simplistic. It is difficult to develop a linear chain of causality to describe the development of the crisis. In part, this is because the causal relationship between variables can run in both directions - between falling asset prices and a reluctance to lend, for example - and it is exactly these negative feedback loops that can be most dangerous.

I have also ignored the question of the role of fiscal, monetary and regulatory policies during the incubation of the crisis - in itself an important topic. I will instead focus on the policy challenges of dealing with the crisis now that it is here.

Let me show you a couple of slides that illustrate the size of the economic disruptions that we have been facing and the speed with which things have moved.

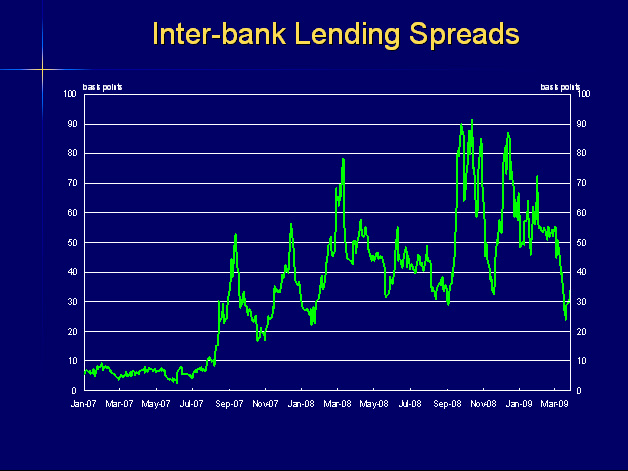

Slide 1: Inter-bank lending spread

First, this chart shows for Australia the spread of the 90-day bank bill swap rate to the overnight indexed swap rate - essentially a measure of the risk that Australian banks perceive in lending to each other.

You can see that this spread had been consistently very low until the effects of the global financial crisis began to become evident in late 2007 and early 2008. There was a significant increase in the spread in September last year following the collapse of Lehman Brothers in the United States.

And remember that these rates are for Australian banks, the largest of which are very strong AA-rated institutions with long experience of each other's business models; the uncertainties brought about by financial crises can truly be pervasive.

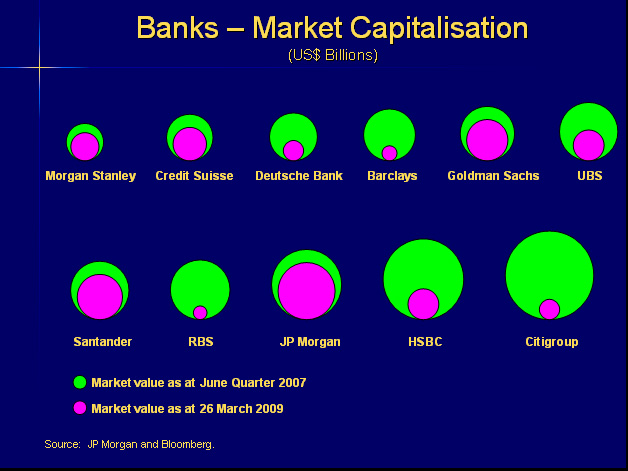

Slide 2: Banks - Market Capitalisation

My second slide has been doing the rounds - developed initially by JP Morgan, I think - but it is quite striking and I reproduce it here for those of you who have not yet seen it. The large circles are the market capitalisations of some major financial institutions immediately before the current crisis, and the smaller interior circles are the market capitalisations of those same institutions today.

You can see the profound reassessment of many banks and financial institutions that has taken place in the past year and a half. The clear view of investors is that the potential of these institutions to add economic value is now much lower than it was. It is also not too far a jump to suggest that their potential had also been significantly overstated before the crisis.

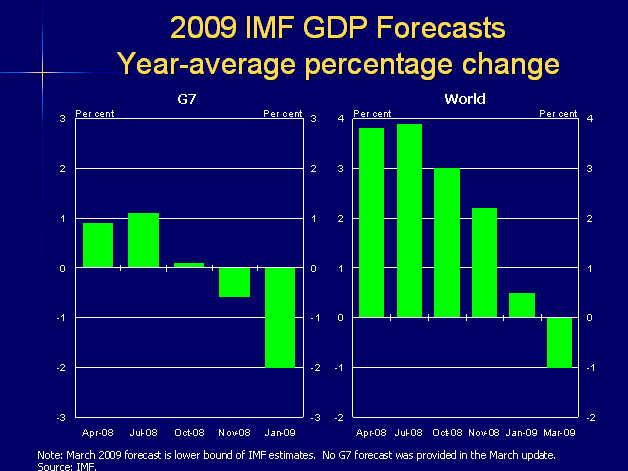

Slide 3: IMF GDP forecasts

My last chart on the global financial crisis shows the evolution of the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) forecasts for global growth. You can see that Fund staff have been continually reassessing the effects of the crisis. Their current forecasts, if realised, would be the worst global growth outcome since World War II.

I certainly do not want to suggest that the IMF is any worse at economic forecasting than anyone else. Most national government and private sector forecasts would show a similar pattern of revision.

The point is that, even when the crisis is on top of us, it is still very difficult to predict its full ramifications for the economy. To be frank, we are just not that good at mapping financial market developments through to real economic outcomes. In part, this reflects the fact that consumer and business confidence, which are extremely difficult to measure with any accuracy, are of critical importance in determining how the economy reacts to financial market turmoil.

Objectives of economic policy

While we may have difficulties in quantifying the effects of the crisis, we can now be pretty sure what those effects might look like in qualitative terms. The question then is what are the appropriate objectives of public policy in these circumstances?

The Treasury spent a lot of time earlier this decade thinking about the characteristics of good economic policy and the difficult trade-offs that can be involved in formulating policy. We have published some of this work on what we call our wellbeing framework 2.

The current circumstances are highly unusual in many respects. Australians face a potentially very large threat to their wellbeing - potentially as large as any threat most of us have seen. And the objective for economic policy seems unusually clear, if, perhaps, slightly old-fashioned: we should use economic policy to try to keep national output as close to potential as we can, subject to some important longer run constraints. That is, we should mitigate the effects of the financial crisis on economic output where possibl

e, without stimulating the economy so much as to generate inflationary pressures on the other side or to introduce structural impediments to growth.

This is pretty close to Keynes's idea of trying to stimulate effective demand in the economy.

It is also important that we continue to expand our productive capacity over time - it would not make much sense to close the output gap by just reducing our productive potential.

There should also be a distributional aspect to our response. We need to look after those Australians who are going to be hurt most by the effects of the crisis, particularly where they do not have the resources to look after themselves. This objective is defensible on social grounds. It will also help people to remain attached to the labour force and allow them to contribute again once the economy begins to recover.

Arms of the policy response

What tools do governments have to try to achieve these policy objectives and how should they be used?

I would like to classify the policy tools into three broad categories for the purposes of today's discussion: monetary policy, financial system policies, and fiscal policy. I will also argue that many financial system policies are substitutable for more traditional fiscal policy measures and therefore they share a number of important characteristics.

1. Monetary policy

First, let me speak very briefly about monetary policy.

In the 1990s, governments and economists reached a broad consensus on the appropriate use of monetary policy as the first line of macroeconomic demand management policy. There was broad agreement that monetary policy was best conducted by an independent central bank that was able to control some sort of official interest rate and had an objective - sometimes explicitly formulated - of controlling inflation 3. For advanced economies, open capital markets and a floating exchange rate almost always accompanied this prescription.

There was some debate, of course - perhaps most notably around whether the inflation target should address only consumer prices or something broader - but the unanimity of view was remarkable given the debate that had occurred in this area from the 1950s to the 1990s.

I think that the novelty and breadth of this consensus, along with the observed success of the new monetary policy regime, was an important reason for discretionary fiscal policy's being talked about less. That is not to say that it was never used. Here in Australia, the then government used discretionary fiscal policy as the economy came out of the early 1990s recession. But monetary policy was clearly the primary tool.

In recent months, the Reserve Bank has acted very quickly to bring down official interest rates with the aim of stimulating demand. Central banks around the world have also moved expeditiously.

In some other countries, it is probably the case that the effectiveness of stimulatory monetary policy has been muted because of the seizing up of credit markets. And in some countries - again notably not Australia - the effectiveness of monetary policy has been inhibited by the fact that interest rates can only go so low; they are close to reaching the so-called zero bound.

2. Financial system policies

Let me move now to financial system policies.

An obvious solution, when faced with a situation like we have been, is to try to address the problems in credit markets directly.

As I alluded to earlier, Australia is in the fortunate position of having a well-capitalised, profitable banking system. We have four of the 11 major banks with a AA or better credit rating.

Still, our banks do rely on international credit markets for a share of their funding and they are therefore not immune from the effects of disruptions in those markets.

When foreign governments began to guarantee the debt of their home banking sectors, this put Australian banks at a disadvantage in attracting capital, potentially threatening their intermediation of credit to businesses and households. The Government decided that the appropriate response was to address this threat by offering a similar guarantee for the Australian banking sector.

In essence, what governments are doing is using the strength of their own balance sheets to support financial intermediation, and hence real activity.

There have been a number of other measures taken in Australia and overseas that share this characteristic of the government's using its own balance sheet to support the liquidity of credit markets.

I mentioned earlier that many of these policies are substitutable for more traditional fiscal policy measures. What I mean is that, rather than using its balance sheet to support financial intermediation, a government could use fiscal policy directly to support real activity in the economy.

There is a hierarchy of responses open to the government. Take the example of the bank funding guarantee. The government could, as it has done, guarantee bank debt; it could issue its own debt and lend to the banks; it could make loans directly to businesses and households, circumventing the banking system; or it could buy goods and services directly and transfer them to businesses and households.

All of these options share the characteristic of the government's use of its balance sheet to support economic activity, even though we would usually think of the former options more as financial system measures, and the latter options more as fiscal policy measures.

What then is the advantage of the approach that the Government has chosen relative to the others on my list? I think that the main one is that it leaves in place a system that is closest to the one we would like to have when conditions are normal. History and common sense tell us that public servants are probably not the people that you want directing every investment decision in the economy, so it is sensible to limit policy interventions to those areas where there is a clear rationale for government involvement.

3. Fiscal policy

Let me turn to fiscal policy in its more traditional guise.

Most economists accept that there may be a role for fiscal policy in addressing short-term fluctuations in demand that cause the economy to operate well below potential. In this situation, governments can use some combination of increased spending on goods and services, increased transfer payments to other sectors of the economy, or reduced taxation to stimulate demand in the economy.

In the current crisis, governments have adopted expansionary fiscal policies in an effort to support economic activity by stimulating aggregate demand. There has been a high degree of international cooperation in these measures, through the involvement of international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, and in multilateral forums such as the G-20.

The implementation of an expansionary fiscal policy can be difficult.

First, there is an issue of timing. You want to find a policy that acts quickly so that the stimulus is provided when it is needed, and not when it is too late. Even before you do that, you need to recognise the need to act early enough.

Second, and related to the first, you want a policy that can be withdrawn or whose effects diminish as the economy recovers. Otherwise, the result may be inflation, a crowding out of private sector spending, or a permanent deterioration in the government's budget position.

Third, fiscal measures are most effective if they are aimed at sectors where there is spare capacity or a greater propensity to spend money quickly.

And finally, while economic theorists often think of fiscal stimulus in terms of a generic injection of government money to boost the economy, in the real world we might also want our fiscal measures to increase the longer term productive capacity of the economy.

Most policies will involve some form of trade-off amongst these different cr

iteria. Infrastructure spending should boost the economy's productive capacity, but it might involve long lead times for planning. Transfer payments can be increased quickly, although, unlike direct purchases of goods and services, some of the payment might be saved, at least initially.

The measures chosen will determine how much of an effect the fiscal stimulus will have on activity - commonly called the multiplier - and over what time period that effect will take place. This is not a precise science, but contemporary empirical evidence suggests that fiscal stimulus can have a significant impact on economic activity 4.

Coming back to the Australian experience, there has been a very healthy public debate on how much fiscal stimulus is appropriate and what the nature of that stimulus should be.

What seems clear is that the economy is now entering a period in which it will be operating below potential for a period of time - the unemployment rate has already begun to increase and we expect it to increase further still before the economy begins to recover. If we accept that fiscal policy can have a role in ameliorating the effects of economic fluctuations, then the case for using it now is very compelling.

And because the current downturn has been triggered by such momentous global events, particularly the massive loss of confidence in September 2008, the Government has been able to foresee the need to act earlier than in some previous episodes.

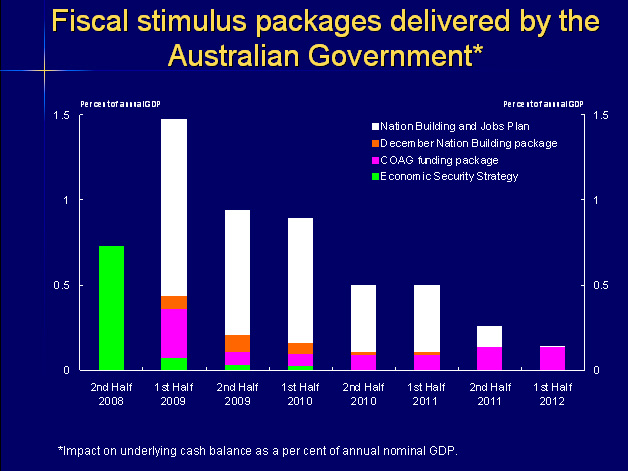

Slide 4: Fiscal stimulus packages delivered by the Australian Government

This chart shows the timing of the fiscal stimulus packages delivered by the Australian Government. You can see that the bulk of the spending is to be delivered quite soon - at a time when we know the economy will be feeling significant effects from the international downturn. The stimulus spending will then be withdrawn over approximately three years, as the economy is expected to begin to recover.

The elements of the stimulus spending that involve transfer payments to households have been designed to be timely, temporary and targeted. That is, they are being delivered quickly, to those most likely to be hurt by an economic slowdown, and are withdrawn as the economy recovers.

Direct government spending on goods and services and infrastructure has, similarly, been designed to be delivered as quickly as possible, when the economy is likely to need support. This does mean, however, that the infrastructure projects most suitable for this purpose are those for which work can be commenced within relatively short lead times.

There has been some questioning around whether households will spend additional transfer payments or choose to save them in the current environment. This type of argument is relevant for our expectation of the size and timing of the fiscal multiplier. But we should cast the argument in terms of what would have happened in the absence of an increase in transfer payments.

It is plausible that households are directing more of their income to saving or paying down debt in the current environment. This should mean both that they reach their desired level of gearing more quickly and that their confidence about their financial position increases. Either directly, or through balance sheet effects, the transfer payments will have a positive impact on spending.

The Treasury's analysis of the Government's recent policy action indicates that, absent the fiscal stimulus, household consumption would have remained below its level of the middle of last year until late this year. The stimulus is expected to hold household consumption above its level of the middle of last year.

Fiscal sustainability

Let me turn now to some other considerations for fiscal policy, particularly around the sustainability of policy in the medium term.

First, there is the traditional concern of crowding out. Put simply, this is a concern that increasing government spending will tend to put upward pressure on interest rates or the exchange rate and depress private sector activity.

This shift of resources from the private sector to the public sector is more pronounced when the economy is operating near potential - that is, near the point where labour and capital are fully employed. In the current circumstances, the unemployment rate is rising. So the risk that fiscal stimulus will result in increased inflationary pressure or crowding out of private sector activity is significantly reduced.

A related concern at the moment is the risk that the Government's issuance of AAA-rated sovereign bonds could 'crowd out' other borrowers in debt markets, particularly if investors are trying to reduce their risk profile which probably has been the case recently. But even with the proposed increase in issuance of Commonwealth Government Securities, the Australian Government's bond program will remain small relative to the size of the overall domestic and international debt markets.

Another consideration for the sustainability of fiscal policy is that of intergenerational equity.

Fiscal stimulus can, to some extent, be justified on equity grounds: in a sense, income is being redistributed from more prosperous to less prosperous periods in time. Successful discretionary fiscal policy may also provide a more solid base for future economic growth, boosting national income over a number of years relative to what it would have been in the absence of government intervention. And we also need to consider the nature of the government spending: successful investment spending will yield economic dividends to the community or financial dividends to the government, providing a positive return for future generations.

The government also needs to ensure the long term sustainability of its budget position. Sustainability is a difficult concept to define for governments, not least because a government's power to levy taxation is difficult to value, as are the expectations of the community for future government spending. So, even financial sustainability is difficult to determine precisely.

And, if we include some of the issues that I mentioned earlier, the definition of sustainability can be broadened to include other criteria, such as the promotion of economic growth, intergenerational equity considerations, or the meeting of explicit commitments on spending and taxation 5.

So, where does this leave us? Fiscal sustainability is a complex issue, and many of the judgments involved are difficult. It is, ultimately, a government's job to make these difficult calls. But, having made those judgments, it is important for the government to articulate its fiscal objectives and the strategies that it intends to follow to achieve them 6.

In the Updated Economic and Fiscal Outlook released in February, the Australian Government nominated supporting the economy as its immediate priority. This will be achieved by allowing the automatic stabilisers to work and by providing fiscal stimulus as required.

The Government then plans to return the budget to surplus as the economy recovers by holding real spending growth to 2 per cent a year and allowing tax receipts to recover naturally.

In the medium term, the Government's strategy is to achieve budget surpluses, on average, over the economic cycle; maintain taxation as a share of GDP below its 2007-08 level on average; and improve the Government's net financial worth.

As I argued earlier, the Government's interventions to support credit markets and the broader economy are very important aspects of its response to the global financial crisis.

But, equally important is its focus on the medium term sustainable position for the b

udget. History shows us that the ability to sustain a substantial fiscal expansion over a longer timeframe is limited. The experience of Sweden and Finland in the Nordic Banking Crises of the early 1990s demonstrated this, even though they started the crises in relatively strong fiscal positions 7.

In addition to looking at the fiscal balance, the balance sheet is an important metric by which the medium term fiscal strategy will be judged. The balance sheet gives us a fuller picture of the assets and liabilities of the government, and hence of the economic resources at its disposal. It values some of the liabilities, such as public service superannuation, that will involve a financial cost over coming decades, alongside the assets that have been set aside to help provide for those liabilities.

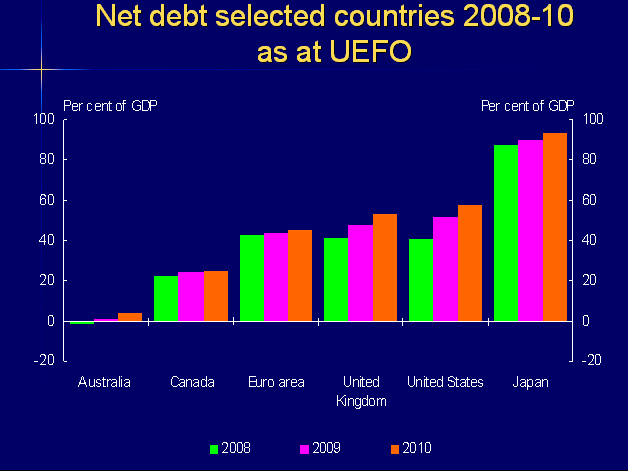

Slide 5: Net debt of selected countries

As the world entered the current downturn, the Australian Government's balance sheet was very strong- net debt had been eliminated and net financial worth was strong by international standards. The Government had the opportunity to leverage off the strength of the balance sheet to respond quickly to the challenges that the economy was facing - a demonstration of the power of maintaining a relatively conservative fiscal position in the good times to build capacity to support the economy through more difficult circumstances.

The chart shows that the Government's net debt position remains very strong, after both the discretionary fiscal action and the operation of the automatic stabilisers on the budget.

Conclusion

The global financial crisis, and the policy actions of the Government to ameliorate its effects, illustrates the potential role for fiscal policy in macroeconomic adjustment, particularly in the face of large shocks.

It is still important to deal with crises as close to their root as possible. In this case, it is measures aimed at strengthening financial intermediation that will lay the foundation for economic recovery.

But monetary and fiscal policies have an important role to play in smoothing the adjustment path of the economy. They have the capacity to reduce the economic and social costs of the downturn. While monetary policy and the automatic stabilizers that operate on the budget are the primary stabilisation tools, discretionary fiscal policy can support monetary policy. This is particularly the case in the face of the large shocks currently affecting the Australian economy.

Still, it is important that discretionary fiscal policy is set within a medium term framework that allows the Government to meet its longer term fiscal objectives.

References

Auerbach, Alan J., 2008, "Long-Term Objectives for Government Debt," Paper presented at a conference on Fiscal Policy and Labour Market Reforms organized by the Swedish Fiscal Policy Council.

Department of the Treasury, 2004, "Policy Advice and Treasury's Wellbeing Framework," Economic Roundup, Winter, pp. 1-20.

Goodfriend, Marvin, 2007, "How the World Achieved Consensus on Monetary Policy," Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 21(4), pp. 47-68.

Hemming, Richard, Michael Kell and Selma Mahfouz, 2002, "The Effectiveness of Fiscal Policy in Stimulating Economic Activity - A Review of the Literature," IMF Working Paper 02/208 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

International Monetary Fund, 2008, "Fiscal Policy as a Countercyclical Tool" in World Economic Outlook: Financial Stress, Downturns and Recoveries (Washington: International Monetary Fund), pp. 159-196.

Kent, Christopher and Simon Guttman (eds), 2004, The Future of Inflation Targeting (Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia).

Krugman, Paul, 2005, "Is Fiscal Policy Poised for a Comeback?" Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 21(4), pp. 515-523.

Lowe, Philip (ed.), 1997, Monetary Policy and Inflation Targeting (Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia).

Schick, Allen, 2005, "Sustainable Budget Policy: Concepts and Approaches," OECD Journal on Budgeting, Vol. 5(1), pp. 107-126.

Solow, Robert M, 2005, "Rethinking Fiscal Policy," Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 21(4), pp. 509-514.

Spilimbergo, Antonio, Steve Symansky, Olivier Blanchard and Carlo Cottarelli, 2008, "Fiscal Policy for the Crisis," IMF Staff Position Note 08/01 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

1 See, for example, Solow (2005) and Krugman (2005).

2 See Department of the Treasury (2004).

3 See Goodfriend (2007) for a discussion of the international experience, and Lowe (1997) and Kent and Guttman (2004) for several papers on Australia's experience

4 See International Monetary Fund (2008) for a general discussion and Hemming, Kell and Mahfouz (2002) for a review of the literature.

5 For a summary of these issues, see Schick (2005).

6 See Auerbach (2008) for a discussion of fiscal objectives and sustainability.

7 For a discussion, see Spilimbergo et al (2008).