Downloads

I would like to acknowledge the contribution of my Treasury colleague Tim Wong in the preparation of this address.

Introduction

I would like to thank the Ai Group for inviting me to be with you today. The theme of this year's forum - Making Sense of Good Fortune ‑ is very appropriate.

As everyone here knows, Australia and the world are going through an unusual period of upheaval and transformation. Global economic weight is moving toward the emerging market economies and away from the advanced economies. The rapid pace of globalisation, and the economic re-engagement of at least one‑third of the world's population, combined with the troubles plaguing parts of the developed world have resulted in a 'multispeed' global economy.1

Stellar growth in the 'fast lane' — the populous emerging economies — has resulted in an unprecedented pace of industrialisation and urbanisation. This has been the case for the Asian giants, China and India, but is also true for others in our region (for example Indonesia and Vietnam) and beyond.

This shift in the world's economic clout has been underway for some time but the momentum accelerated abruptly with the advent of the global financial crisis.

The forces driving those Asian economies in the 'fast lane' have major implications for Australia, including for the shape of our industries.

Today, I would like to make some remarks about these profound global transformations and to reflect upon some of their implications.

In doing so, though, it's worth beginning with an overview of those countries in the global 'slow lane' — not just for the sake of completeness, but because the plight of much of the developed world provides a helpful counterpoint to Australia's current circumstances.

The global slow lane

The outlook for the world's major advanced economies has become markedly uncertain — with recovery remaining fragile and downside risks intense. Growth almost everywhere has been sluggish with the US economy weaker in the first half of 2011 than in the second half of 2010. Many of the advanced economies face persistently high rates of unemployment — around 10 per cent for the euro area, 9 per cent for the US and 8 per cent for the UK.

The effects of the sovereign debt crisis in Europe pose a key risk, especially for the European banking sector but also for global financial markets more broadly.

Most of the advanced world faces serious long‑term fiscal challenges. This is not just a point about their recent sharp accumulations in public debt — which would not be as problematic if they were merely cyclical. Rather, and this is particularly the case in continental Europe, these challenges relate especially to a loss of international competitiveness and a failure to pursue much needed structural reform. The result has been unsustainable tax and transfer settings and a build-up of sovereign debt. And all this occurs against a backdrop of long term pressures on these economies — especially demographic change — and an emerging sense that their political institutions are incapable of an effective response.

The challenge, therefore, for many advanced economies is to manage fiscal consolidation while at the same time promoting sustainable growth and improved competitiveness.

Australia's starting point could not be more different.

It is not that we face no challenges – we do, and they are large – nor that we are impervious to events in the US and Europe. Rather, it is that as we manage the structural transformation of our economy, re‑invigorate our productivity performance and prepare for an ageing population, we do so with sound fundamentals and with great opportunities.

The public balance sheet is in an enviable position compared to the rest of the developed world and our financial institutions are well regulated and capitalised. While consumer caution is dampening growth, it also means that household balance sheets are strengthening.

Australia's policy frameworks have provided us with an effective shock absorber in the face of global events. The flexibility of our market‑determined exchange rate and our credible medium‑term approach to monetary policy have cushioned volatility and helped to smooth demand and inflationary pressures. These have been complemented by sound fiscal policy settings – including a clear focus on returning the budget to surplus and paying down the small (as a share of GDP) stock of debt built up in recent years.

In decades past, an external shock (or 'impulse') from the terms of trade would have been spread ('propogated') throughout the economy by our then fixed exchange rate and centralised wage-fixing system, resulting in high inflation, declining competitiveness in many industries and sharply rising unemployment.

As a result of the reforms of the last quarter century, today's external shock is still affecting the competitiveness of individual sectors yet inflation remains controlled and unemployment low.

In short, we are seeing, and will continue to see, our past reforms paying healthy dividends, notwithstanding the painful adjustment underway in some industries (such as manufacturing, education and tourism services) as a result of the higher exchange rate and the capacity of the mining sector to bid away skilled labour.

It is also unsurprising that as the extent of the transformation being thrust upon us becomes more apparent that there would be some calls to resist change. In some cases, even for a return to hidden and not so hidden forms of protectionism.

The issue here is not just the budgetary cost of the explicit transfer of resources through such protection. Our history suggests that unsheltered workers and businesses would lose out if a small number of select producers were supported in resisting adjustment.

Our history also shows that protection represents a transfer of resources and opportunities, both explicit and implicit, away from consumers towards that same small number of sheltered producers.

In short, responding to these calls would fly in the face of the lessons from our history, lessons that we learned the hard way. With the passage of time it is perhaps all too easy to now forget that our history was littered with the failures of winner-picking protectionist policies in the post-war period — what is less reasonable is to forget the success of the deregulatory and liberalisation agenda of the last quarter century.

Don't get me wrong – I am not advocating we do nothing to assist the management of this economic transformation, that the Government wipe its hands of the challenge. To the contrary, Government has a clear responsibility to assist, but how this is done and over what time period is critical. And there is no magic pudding. Any action taken will come with costs and these need to be recognised.

Good policy actions will help industry, workers and regions adjust, not just to the circumstances we face today, but to what we will face in the decade(s) ahead.

In particular, it is clear that emerging market economies are moving up the value‑add chain in many areas, but particularly in manufacturing.

Our comparative advantage is, therefore, shifting and we too need to continue the move into niche markets, find new places in global supply chains and become world leaders based on technology and knowledge advantages.

Our manufacturing sector is not homogeneous and many of our firms are already doing this – they are highly innovative, successful and productive, notwithstanding the level of the exchange rate. But other parts of our manufacturing sector will need help to evolve, to transform, to adapt.

Individuals and businesses will need to adjust and innovate in the face of change, and policy interventions should focus on helping firms to help t

hemselves. Policy settings which foster investment, innovation and skills, and enhance business management capabilities and networks, help build on Australia's existing comparative advantages — and encourage new competitive one.

It is also imperative that we do not wind back the clock on the structural reforms that have helped us avoid the difficulties plaguing the rest of the developed world. Suggestions that we intervene to "adjust" the exchange rate fall into this category. But resisting backsliding is not enough – we need to continue to think carefully about what next in our reform agenda. If we think that all that is needed is to reprise what's been done beforehand, which appears to underlie some of the comments on industrial relations, then we have completely misjudged the magnitude of the transformation underway.

Let's be clear. As competition intensifies, as the global economy transforms, and as our population ages, we will need to look to further improvements in productivity to lift Australian living standards.

Productivity is not about working harder or longer but about working smarter with what we have. This requires quality infrastructure, a competitive tax system, a highly skilled and flexible labour force and top notch management skills able to innovate and capture opportunities.

Many of these productivity improvements will increasingly be found in new areas, especially the services sectors — in education and training, in health and in aged care. Others will come from continued efforts in existing areas, facilitated by increasing competition, revisiting market structures and continuing the reform of our tax system.

Needless to say, the ability to deliver these reform outcomes will invariably depend on the capacity of Australia's institutions. The Commonwealth's actions in many areas are central. But in a Federation, so are the actions of collaborative institutions such as COAG. Reforms are not just a Commonwealth responsibility. The commitment of the states and territories is critical to delivering on the productivity challenge.

The global fast lane

One of Australia's major tasks is to make the most of the opportunities emerging as the rise of Asia fundamentally re‑shapes our economic future.

The rise of Asia and the resources boom

Despite accounting for almost 40 per cent of the world's population in 1990, China and India together only accounted for less than one-tenth of the world economy. However, the rapid pace of their continuing emergence is shifting the centre of world economic activity.

In 2010, they accounted for around one-fifth of world GDP: in 2020, this could rise to more than a quarter — the equivalent to the combined share of the US, Japan and the ASEAN-5 — and by 2030 they could account for around one-third of the world economy.

The resource intensity of their economic development — underpinned by the rapid growth in their industrial base and the urbanisation of their population — has boosted the demand for Australia's mineral and energy resources and resulted in historically high prices for Australia's exports.

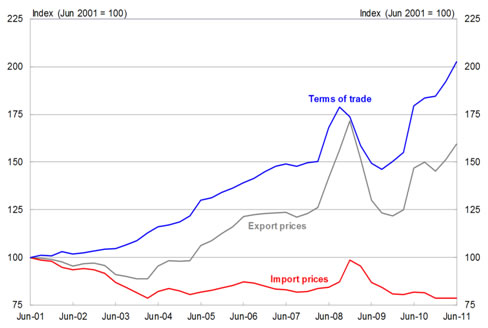

So we are in the midst of the largest and longest terms of trade shock in our history — boosting the purchasing power of our exports and lifting our national income (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Terms of trade

Note: Export and import price indices are denominated in Australian dollars and will reflect movements in the nominal exchange rate.

Source: ABS cat. no. 5302.0 and Treasury.

As I have mentioned elsewhere, it was as if we woke up one morning to find that global forces have conspired in our favour to increase the value of Australia's national wealth. 2

On numerous occasions, my colleagues and I have discussed the implications for Australia's mineral and resource exports and I do not intend to reprise that here.3

The rise of Asia and industrial production

However, what is often overlooked in the discussion of Australia's terms of trade is the role of the price of Australia's imports, that is, the denominator in the terms of trade.

The secular downward pressure on the price of manufactures over the last ten years has boosted the purchasing power of Australian firms and consumers as we are net importers of these goods. The main contributors have been imports of capital goods and intermediate inputs.

Put another way, if we did things to stop those lower prices coming into the Australian economy we would have been deliberately raising the costs of producing other goods and services here, making ourselves poorer in the process (to say nothing of giving us higher inflation!).

In part, the decline in our import prices has reflected global productivity improvements. But it has also been a direct result of permanent changes in global economic structures. As the big emerging economies re‑engaged the world, they have developed large, low cost manufacturing centres reflecting their comparative advantage. They have, amongst other things, drawn upon their sizeable and relatively cheap labour force.

For example, in 2010, Chinese and Indian employment combined was estimated to be around 1¼ billion (which is half the size of their collective population). By comparison, US employment was around ten percent of this figure while Australian employment was less than one per cent.

And it should not be surprising that their labour costs are relatively low. Many workers in developing economies have come from poverty and subsistence, seeking material advancement. The much higher (and rising) wage rates on offer in the urban manufacturing centres – while still lower than in the developed economies – are a powerful magnet pulling underutilised labour from agriculture to manufacturing, much as it did in the developed economies during the Industrial Revolution.4

Just this cursory glance should give an appreciation for the scale of their existing and future comparative advantage and, hence, in their capacity to impact the structure of global markets.

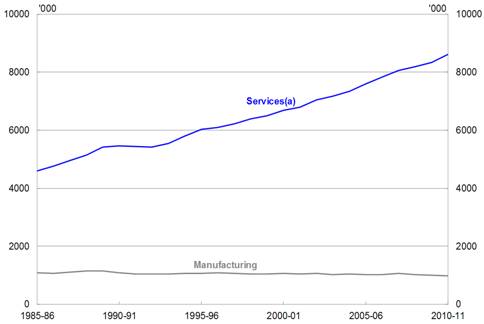

At the same time, existing global manufacturing centres have faced greater competition from the emerging economies in these more commodity-style manufactured goods— that's why we've seen the falling price everyone receives, and pays, for these products. It should not be surprising, then, that the emergence of the developing economies has seen manufacturing employment in the advanced economies continue its decline as a share of total employment.

This is neither new, nor uniquely Australian (Chart 2). It is also neither new nor uniquely Australian that a primary driver of employment has been the rise of the services sectors, which has more than offset the decline of manufacturing employment.

Chart 2: Manufacturing and services employment in Australia

(a) Excludes construction, electricity, gas, water and waste services.

Source: ABS cat. no. 6291.0.55.003.

As I mentioned earlier, as countries get richer their producers move up the value added chain, just as we did as Australia developed.

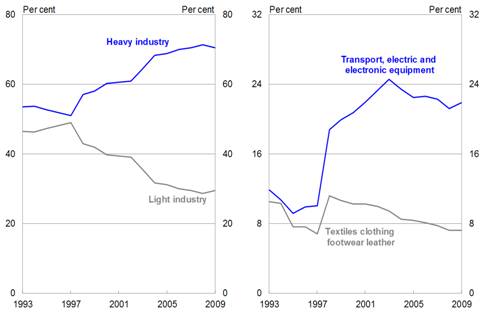

For decades, Chinese industrial output was split evenly between light industries (which are broadly those producing goods like textiles and clothing) and heavy industries (which broadly produces capital goods, including intermediate inputs) (Chart 3).

Chart 3: Share of Chinese total gross industrial output, by industry

Source: CEIC China database

Since the pace of China's economic expansion took-off in the mid‑90s, this composition has been changing. While all industries have expanded rapidly, light industrial output has declined relative to the heavy industries.

As part of this, Chinese producers moved up the value chain to make items that were, for many decades, predominantly the domain of producers in developed countries.

The production of transport equipment (including cars) rose from around five to eight per cent of industrial production over this time — with motor vehicle production rising from 1.3 million units per year in 1993 to 18 million in 2010.

For China to continue to deliver rising living standards, and to offset the impact of even newer emerging economies, it will need to continue to move up the value chain. The available data suggests that wage costs are escalating at a rapid pace, with nominal wages in Chinese manufacturing rising at double‑digit rates over the last decade. Such wage growth, combined with their rate of productivity growth, is reducing their relative competitiveness in low‑value added production. So even while China's nominal exchange rate may be relatively inflexible, the signs are that their real exchange rate is rising.

It's not hard to see how the trends we are now seeing in China and elsewhere parallel the history of economic evolution in the West, including Australia in the first half of the 20th century.

As labour costs escalated, technologies advanced and as tastes changed, Australian processing industries that were intensive in low skilled manual labour became uncompetitive and gave way to up‑and‑coming forms of industrial production. Our emphasis moved away from dyeing cloth and tanning leather towards activities that we would now ascribe as 'hallmarks' of 20th century progress: automobiles, whitegoods, machinery, and chemicals.

The latter part of the 20th century saw further transformation. The protectionist measures that had been sheltering domestic producers buckled under the weight of global economic forces — having held back Australian living standards for many decades. As tariff walls, onerous product market regulations and inflexible institutions became unsustainable and were eventually dismantled in the 80s and 90s, Australian producers were placed under great pressure.

But rather than trying to continue making low value goods for the lowest possible cost, many Australian producers successfully moved up the value chain.

Even today, more and more stories are emerging of Australian manufacturers finding ways to add value, make their processes more efficient, offshoring parts of their operations, cornering their place in global and domestic markets and beating their competition.

These industrial trends have been the norm in other advanced countries.

Examples that immediately come to mind include Germany and Japan. As the lower end of the market became tight, they outsourced low-skilled assembly lines to low cost manufacturing centres — including Eastern Europe and Asia. However, the production of premium and specialised goods — as well as design services, marketing services, intellectual property and management acumen — were retained domestically.

There is a certain distinction attached to premium goods that are 'designed in Germany' or 'made in Japan'. Rather than being the cheapest goods, they are labels that signal quality. It is my view that the same cachet can and should be attached to those premium goods made or designed in Australia.

As the transformative forces of globalisation continue to play out, the determinants of the future success for Australian industry will continue to be found — just as always — in adaptation and innovation.

The structures of our economy and of our businesses have never stood still. And so, inevitably, the path to prosperity involves creating and adapting business models. Hoping and waiting for external conditions to become benign for existing business models risks stagnation and failure.

The rise of Asia and the burgeoning global middle class

But the story of the global fast lane does not end here. The resource boom and the global trends in manufacturing are merely the early, but probably the most obvious, manifestations of Asia's rise. The risk facing us today is that, because of the immediacy of the challenges, our attention is forced away from the long‑term horizon towards the ground at our feet.

The changing world economy will continue to present opportunities for Australia as the Asian middle class rises.

The Asia Pacific region could have more people in the middle class than the rest of the world combined by 2020. China could have a middle class market that surpasses the US in dollar terms. By 2030, if India follows China, two thirds of the global middle class, around 3.2 billion, could be in the Asia Pacific region.

None of this is preordained and, as I have said elsewhere, there are no guarantees that the emergence of China and India will follow a smooth path.

Rightfully, questions have been asked: 'What if Chinese growth slows? What if these economies are unable to rebalance? What about the possibility of policy missteps?'

These concerns are sensible and one needs to be humble in projecting the future ‑ Treasury's thinking about Australia's economic future attempts to factor in these medium‑term risks.

Nevertheless, we are already seeing some of the benefits of the rise in the Asian middle class. Global demand for agricultural commodities, tourism services and for consumer durables has been boosted over the last decade — as increasingly well-off Asians seek a better quality, more protein-rich diet, the greater comfort of 'mod cons' and different cultural and recreational experiences.

Because of our regional ties, these are huge opportunities being brought closer to Australia's doorsteps. The unanswered question is whether we are we up to grasping them.

A further reflection

In light of this, it is worth reflecting on concerns about Dutch disease.

In the written version of the speech I go through this issue in detail but given the time I will briefly touch on it here.

Dutch Disease concerns are overstated

Dutch disease refers to changes in the economy caused by an appreciation in the real exchange rate arising from a commodity boom.

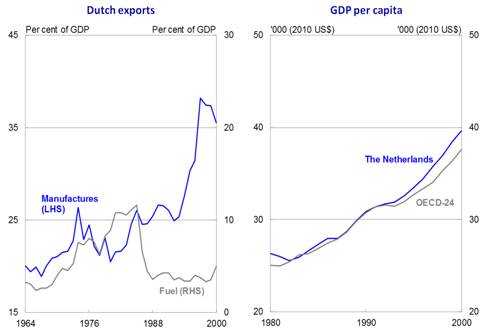

Dutch disease got its name from the anticipated adverse effect on Dutch manufacturing following the 1960s and 1970s exploitation of North Sea gas discoveries. In light of limited gas reserves, the fear was that their temporary commodity boom would permanently harm the Dutch industrial structure — leading to long term economic underperformance, lower living standards and high unemployment.

In recent times, concerns about Dutch disease in Australia have intensified. But is the Dutch situation relevant for Australia?'

One line of concern that I recently heard relates to the size of Australia's resource deposits. But unlike the Dutch, Australia has a great abundance of natural mineral and energy resource wealth.5

But for the sake of argument, let us say that our plight was that the price of our resources plunge. What then?

Dutch disease would only be problematic to the extent that it harmed our long‑term welfare because of future economic underperformance or the creation of entrenched problems like persistently high unemployment.

As Statement 4 in this year's Budget papers went to some length to discuss, the international evidence suggests that Du

tch disease does not reduce overall economic growth. This was even the case for the Dutch — as Chart 4 shows. Dutch manufacturing exports (the blue line on the left panel) declined during an intense period of energy resource extraction (the grey line on the left panel). This period ended in the early- to mid-1980s.

Subsequently, Dutch manufacturing exports rebounded, both as a share of GDP and as a share of total exports. Manufacturing exports continued its resurgence in the 20 years following the Dutch disease period — reaching nearly 40 per cent of GDP and around 70 per cent of total exports in 1997. This period was also matched by solid long term per capita GDP growth (the blue line on the right panel) — matching and, for long periods, exceeding average growth in the OECD (the grey line on the right panel).

Chart 4: Dutch and Dutch disease

Source: Statement 4, Budget Paper No. 1, Budget 2011-12.

But you might ask, 'What about the effect of commodity booms on employment? Didn't the Dutch experience rapid rises in unemployment in the 70s?' 6

Again, the relevance of this line of argument for Australia is difficult to substantiate — as both aggregate unemployment and the spread of unemployment declined during mining boom mark I. The boom has also meant that regions which were previously experiencing difficulties have now benefited from strong income and employment growth.

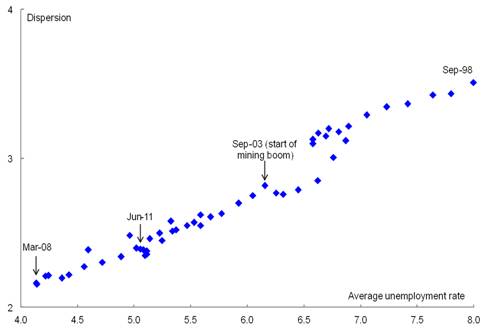

Consider Chart 5, which shows the regional dispersion of unemployment in Australia (the vertical axis) relative to the aggregate unemployment rate (the horizontal axis).

The dot on the top right hand side of the chart shows that, for September quarter 1998, the average unemployment rate was around 8 per cent. The degree to which unemployment was dispersed evenly between the regions is measured by a regional 'dispersion' indicator.7 Referring to the vertical axis, this indicator was around 3½ in September 1998. The bigger the number, the more unequal the distribution of unemployment.

Chart 5: Unemployment across the economy

Source: Statement 4, Budget Paper No. 1, Budget 2011-12 (updated).

Since at least 1998, regional disparities in unemployment rates have declined as aggregate unemployment declined. This relationship has not changed since the onset of the mining boom in 2003. That is, a larger proportion of regions in Australia are experiencing lower rates of unemployment.

This is not to say that outcomes for some regions have not been patchy — I'm thinking of areas like Far North Queensland. Nevertheless, the evidence is that, despite different rates of economic growth between regions and industries, the material gains of our national success are being spread broadly to people across Australia through (amongst other mechanisms) improved labour market outcomes.

We should have strong reservations about the relevance of Dutch disease for Australia. Overstating Dutch disease concerns could mean that we understate the ability and resilience of Australia's people and businesses. In doing so, the risk is that we end up taking actions which would squander the opportunities from global economic conditions swinging in our favour.

What matters…

Let me conclude. As the developing economies in the global fast lane have grown, their rapidly expanding industrial sector and the resource intensive nature of their economic development have led to remarkable benefits for Australia. These trends in the global economy are expected to be sustained into the foreseeable future.

But this also represents a major force shifting the shape of Australian industry — placing pressure on the non-mining parts of the economy to adjust and adapt. This will be an uncomfortable process for many businesses.

But this is not the first time we've had to manage major transitions - Australian industry has always faced continuous change. While not all have been winners, many have adapted successfully and prospered. I believe that Australian business will continue to adapt successfully. But needless to say, this will in many ways depend on the actions of those sitting in this room today.

It will be critical that we in the bureaucracy hear the experience of business as this transformation unwinds and I want to encourage continuing close engagement and candid communication between you, and your representatives such as AiG, and the Treasury.

And while business models need to be innovative and responsive to the changing world, Australia's policy and institutional settings also need to be conducive to the development and use of skills, human capital and investment.

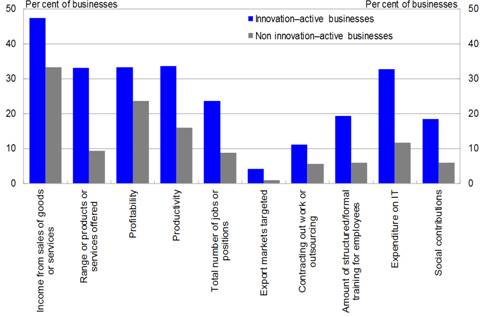

The final chart for today illustrates this point. Chart 6 shows the relationship between firms that are innovative and how well they have performed. As you can see, those firms that see themselves as being active in innovation are more likely to have experienced improvements in performance across a whole range of indicators — profitability, productivity, they have a larger range of products and services, in jobs and positions and also in the amount of training they provide.8

Chart 6: Increases in business performance over the past year by innovation status (2008-09)

Source: ABS cat. no. 8167.0

It is not preordained that Australian business will succeed or fail from the mining boom. In fact, it is not preordained that we will succeed or fail from any of the other manifestations of Asia's economic development.

What we do know is that whether we succeed or not depends on the quality of business and government decisions made today.

Thank you.

1 Spence M, The Next Convergence: The Future of Economic Growth in a Multispeed World, UWA Publishing, 2011.

2 See for example, Parkinson M, ’Sustainable Wellbeing – An Economic Future for Australia’, the 2011 Shann Memorial lecture, 23 August 2011.

3 I would suggest, in particular, reading Statement 4 in Budget Paper No. 1 from Budget 2010-11 and Budget 2011-12.

4 Williamson JG, ‘Migration and urbanization’, Handbook of Development Economics, Volume I, Chenery H and Srinivasan TN (ed.), Elsevier, North Holland, 1988.

5 As a nation, we have the world’s largest recoverable deposits of lead, silver rutile, zircon, nickel, tantalum, uranium and zinc. We rank second in the world for iron ore, bauxite, copper, gold and ilmenite and we are in the top ten for a number of other minerals, including black coal. Geoscience Australia, Australia’s Identified Mineral Resources 2010.

6 The Dutch unemployment rate quadrupled between 1970 and 1975, from 0.9 to 3.7 per cent. Over the same period, unemployment in the United States and Australia, rose from 5.0 to 8.5 and 1.6 to 4.8 per cent respectively.

7 In technical terms, this dispersion indicator is called the ‘standard deviation’ — which, in this ca

se, has been weighted to account for Australian regions of different sizes.

8 See also Soames L, Brunker D and Talgaswatta T, ‘Competition, Innovation and Productivity in Australian Businesses’, Productivity Commission and Australian Bureau of Statistics joint research paper, 2011.