Downloads

Good morning/afternoon.

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to share my thoughts on recent developments in Australia's banking sector. Banking is a topical matter amongst policy makers, industry participants and the community generally.

That level of interest partly reflects the fact that the competitive dynamics in the industry have undergone substantial change in recent years. It also reflects concerns about rising interest rates and views about appropriate levels of profitability of the industry. While we, in Australia, are debating these matters, it is the continuing instability of the banking system that is of prime interest in most other advanced countries.

Notwithstanding its proven robustness, the Australian banking system is facing its own challenges in the post global financial crisis (GFC) environment. These challenges must be of interest to policy makers focussed on enhancing consumer welfare

In this post-GFC environment, those interested in banking policy are grappling with issues relating to the trade off between:

- on the one hand, a regulatory framework that ensures that the banking system is safe and stable; and

- on the other, a case for policy adjustments to stimulate competitive pressures in the industry.

A safe, stable and competitive banking system is critically important for community wellbeing, given the role it plays in people's lives and in the economic fortunes of the nation.

The importance of a safe and stable banking system for sustainable economic growth was brought into sharp focus in the crisis of 2007 and 2008.

Countries with weak banking systems experienced a severe downturn in economic activity in the following period. Notable examples are the United States and the United Kingdom. As those examples are illustrating, economic downturns associated with financial crises tend to be severe and prolonged.

The Australian banks, on the other hand, are well-capitalised and highly-rated. I think it safe to conclude, now, that they have benefited from years of rigorous supervision by better than world-class financial regulators. That quality of supervision is no accident. An important feature of our regulatory infrastructure, for many years, has been a common understanding between governments, the regulators and the regulated of the importance of prudential regulation.

Australian banks have not collapsed. No banking firm needed to be bailed out with taxpayers' money.

The Australian banking system has emerged from the GFC in a stronger position, relative to banking systems in other countries. For good reason, it is highly regarded around the world.

Yet, as I have said, the Australian banking system is facing significant structural challenges in this post-GFC environment.

One such challenge concerns the banking system's capacity to raise funding on cost competitive terms in an environment of continuing volatility in offshore markets, particularly in Europe, and the subdued recovery in the domestic securitisation market following a severe disruption during the crisis.

A second challenge is to foster a competitive banking environment for consumers of banking services, particularly at the retail level, in an industry that has become more concentrated as a result of the crisis.

And a third challenge is to implement the G20's international regulatory response to the GFC. This response is designed to strengthen the global banking sector, taking heed of the lessons learned from the crisis. The challenge for us is to implement the G20 regulatory reforms while taking account of Australia's unique circumstances and avoiding unhelpful impacts on credit flows to the economy.

Today, I want to make some observations on these structural challenges facing the industry. My observations will be framed by a set of trends in a number of areas relevant to system performance, including:

the banking system's role in funding the current account deficit;

- aggregate credit growth;

- the composition of bank funding and developments in the residential mortgage backed securities market;

- the cost of bank funding;

- movements in the net interest margin of the banking system;

- bank profitability; and

- competitive dynamics in the banking sector.

Funding the current account deficit

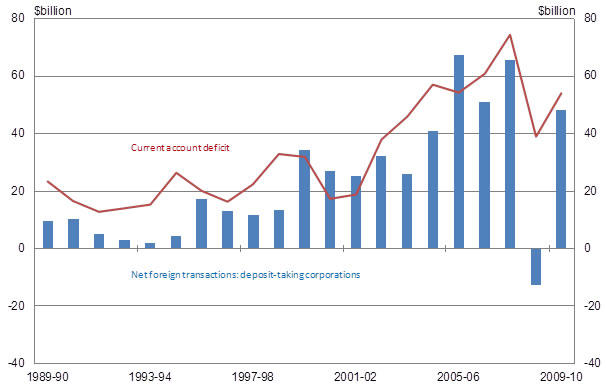

A structural characteristic of the Australian economy is that domestic investment exceeds domestic saving. The gap is the current account deficit. Our current account deficit is strongly correlated with off-shore borrowings by the Australian banking industry, suggesting that the banks play a major role in financing the nation's excess of investment over domestic saving (chart 1).

Chart 1: Funding The Current Deficit

2008-09 - the year of the GFC - was an exceptional year. In that year, the banking sector unwound a small part of its offshore liabilities and the financing of the current account deficit relied to a much greater degree upon equity flows to the Australian corporate sector.

The fact that the banks have intermediated such large flows of off-shore funding for such a long period of time suggests that those undertaking real investment activity have found this source of funding attractive. Borrowing costs have been lower than otherwise. And refinancing risk has generally been considered low.

But the crisis has tested these assessments, serving as a reminder that their validity rests on foreign investors remaining confident that Australian banks are stable and well-regulated, and are able to service what they borrow.

Aggregate credit growth

Another characteristic of the Australian economy over the past 25 years or so is that growth in credit has vastly exceeded the growth of gross domestic product. Aggregate credit expanded from around 50 per cent of gross domestic product in the mid 1980s to around 150 per cent of gross domestic product in the late 2000s.

This growth reflected a significant increase in credit demand, particularly from the household sector, with annual credit growth averaging 15 per cent. The increase in demand was accommodated by new participants, such as foreign banks in the mid-1980s and the emergence of mortgage originators in the mid-1990s; more diverse products; and some easing in lending standards.

In the last three years or so, though, growth in credit has been a little slower than GDP growth: While growth in credit to the household sector has continued to exceed GDP growth, though not by as big a margin as in the previous two decades, growth in business credit has been significantly lower than GDP growth.

This levelling out in credit growth means that the banking system's funding task has eased, but it provides no grounds for complacency - especially given ongoing volatility in offshore financial markets.

Composition of bank funding

Relative to the period prior to the GFC, there has been an increased reliance by our banks on deposits and longer term wholesale funding (including sourced from offshore markets), with less reliance on short term wholesale funding and securitised products (particularly RMBS).

These developments partly reflect a reassessment of risk in the post-GFC environment. They might also be in anticipation of regulatory change in the post-GFC environment, including new international standards on bank liquidity to be fully implemented by 2015.

The greater reliance on deposit and long term wholesale funding, and less reliance on short term wholesale funding, should enhance the stability of the Australian banking system. If sustained, it should enable the system to better withstand any future international liquidity shock.

The Australian Government supported the funding of the banking system during the crisis with the introduction in Octobe

r 2008 of the Guarantee Scheme for Large Deposits and Wholesale Funding.

These guarantees provided the banks continued access to funds on competitive terms during the turmoil. They were critical in supporting a continued flow of credit.

The Guarantee Scheme for Large Deposits and Wholesale Funding were removed with effect from 31March2010.

Even in this more stable environment, the banking system will face a challenge in rolling over 'on cost competitive terms' around $130 billion in guaranteed debt in the period 2011 to 2014. The Government's measure, announced on the weekend, of allowing banks, credit unions and building societies to issue covered bonds should assist in this funding task, supporting the robustness of the banking sector over the medium to long term.

Residential mortgage backed securities market

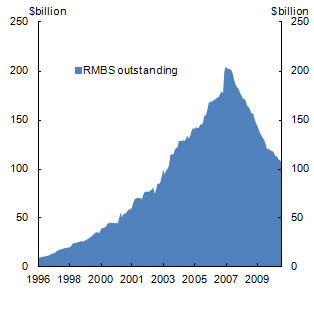

Another development relevant to system performance is the sharp contraction of the residential mortgage back securities (or RMBS) market. This has had its greatest impact on the smaller banks and non-bank lenders.

In the period up to mid-2007, net issuance of RMBS expanded rapidly. This expansion made a significant contribution to the funding of aggregate credit growth, and provided stimulus to competition in the home loan market by enabling the smaller banks and non-bank lenders to access funding on competitive terms.

In the post-crisis environment, the RMBS market has subtracted from credit growth (chart 2). During this period, the Government has chosen to support the RMBS market through the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM). To date, AOFM investments have supported around $26 billion of RMBS issuance.

Chart 2: Australian RMBS Outstanding

It is clear that the GFC has badly damaged investor confidence in securitised housing products globally (particularly in the United States), even though the Australian RMBS product continues to perform well as an investment. While a recovery in the RMBS market is clearly evident, it has been subdued.

For that reason, the Government announced on the weekend that it would continue to support the RMBS market with a new $4 billion tranche of purchases from the AOFM. The Government will also explore options to facilitate the issuance of RMBS structured as 'bullet securities' where the principal is repaid on maturity of the security rather than in an amortised form in the current 'flow-through' structure. The Government has been advised that a bullet structure for RMBS will attract a broader base of potential investors.

These RMBS measures support second tier lenders especially.

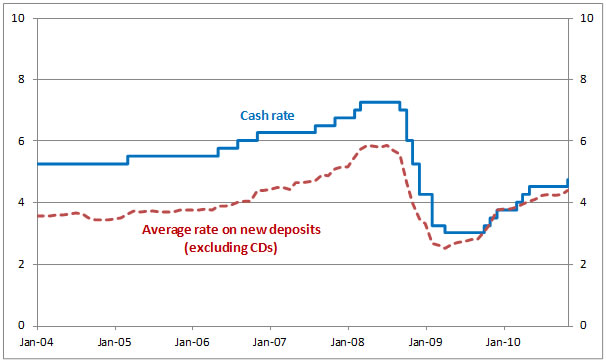

Cost of funding

I noted earlier that competition for deposits has intensified since mid 2008. This competition has seen a significant increase in deposit rates relative to market benchmarks (Chart 3). The intensification of competition is most noticeable in term deposits. It has occurred notwithstanding increased concentration in the banking sector post-crisis.

Chart 3: Major bank deposit rates relative to the RBA cash rate

The RBA estimates that the average cost of major bank's new deposits is currently only slightly below the cash rate, having been around 150 basis points below the cash rate prior to the onset of the GFC.

While net savers, such as self funded retirees, are benefitting from increased returns on deposits, higher deposit interest rates have contributed to upward pressure on lending rates relative to the cash rate.

Bank wholesale funding has also been more expensive. Wholesale funding excluding RMBS represents about 40 per cent of the funding of the major banks and about 30 per cent for the second tier banks.

Spreads for the major banks relative to the risk free government benchmarks in both onshore and offshore markets increased from an average of around 50 basis points during 2006 and 2007 to between 200 and 280 basis points during the crisis. They have since fallen to around 120 basis points, remaining well above pre-crisis levels.

While this change has impacted Australian banks, many other jurisdictions were more heavily affected by the repricing of risk.

Post-crisis, the price of credit has adjusted better to reflect fundamentals. Thus, some part of the repricing should be considered permanent. There probably has been a structural change in the relationship between bank funding costs and benchmarks such as the official cash rate.

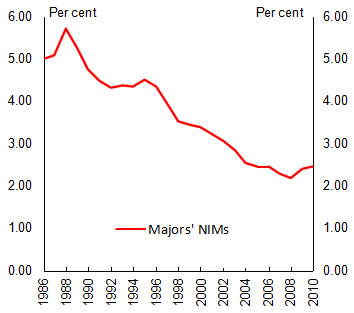

Net interest margin

The overall impact of these developments is reflected in the so-called net interest margin. So too is the level of competition. Where competition is increasing, net interest margins will fall, all else being equal.

Net interest margins of the major banks fell from slightly below 6 percentage points in the mid 1980s to a low of around 2 ¼ percentage points in 2008, immediately before the crisis (Chart 4).

Chart 4: Net interest margin - major banks

The sustained downward pressure on the net interest margin is one of the clearest, long‑term economy-wide benefits of the deregulation of the Australian financial system, including the removal in 1986 of the regulated interest rate cap on housing loans provided by the banking sector. Households and businesses have been the primary beneficiaries of this downward movement in the net interest margin.

Competitive pressures from non-prudentially regulated lenders and new bank entrants in the period since around 1995 also played an important role in the fall in the net interest margin. New technologies that permitted a lowering of the industry's operational costs would also have played a part.

Over the last 2 years, the net interest margin has increased from 2 ¼ percentage points to 2 ½ percentage points - back to 2005 or 2006 levels.

It is too early to judge whether this post-GFC widening can be explained fully by a lessening of competition, but it does provide a case for close examination of the factors affecting competition. The net interest margin needs to be sufficient to absorb bank operational costs and bad debt expenses over the course of an economic cycle, and then to provide a return to bank shareholders on their investment. Thus, the net interest margin will be affected by perceptions of default risk, among other things. But it is doubtful that a rising probability of asset impairment explains the recent increase in the net interest margin. Asset impairment has probably been lower than would have been expected a couple of years ago.

In contrast to the major banks, the net interest margin for the second‑tier banks has generally fallen since the onset of the crisis. Some of this margin compression reflects that the regional banks have incurred a larger increase in their funding costs.

But it is also the case that the second‑tier banks' business lending portfolios are small relative to their mortgage portfolios, and mortgage lending in Australia is usually considered significantly less risky than business lending, even during an economic downturn.

Further small reductions in net interest margins over time are likely, bearing in mind the importance of ensuring that the industry does not become exposed to the sorts of stability issues that affected many countries during the recent crisis.

Bank profitability

The profitability of the Australian banking sector gets a lot of attention.

Since 1992 the industry has recorded a post tax return on equity of around 15 per cent. This is similar to the return of other major companies listed in the A

ustralian Stock Exchange and banks in other countries prior to the GFC.

Is a 15 per cent post-tax rate of return on equity too high or too low? One way of answering that question is to say that it cannot be regarded as too high if the industry is sufficiently competitive; if the provision of banking services is sufficiently contestable. And that is one reason why there is so much focus on banking competition.

Competitive dynamics in the banking sector

The Treasury presentation earlier in the week to the Senate inquiry on competition in the banking sector drew attention to a number of significant developments which have, collectively, altered the competitive dynamics of the retail banking sector in recent years.

The first, mentioned earlier, is the subdued recovery in the RMBS market. This has adversely affected the ability of smaller market participants to raise funding at competitive prices, in turn reducing their capacity to compete against the major banks in the home lending market.

The second development affecting competition is foreign banks withdrawing or scaling back their Australian operations, reflecting their reduced capacity to raise funds and to deploy capital away from their home operations.

And thirdly, there has been some degree of consolidation in the Australian banking sector since the global financial crisis.

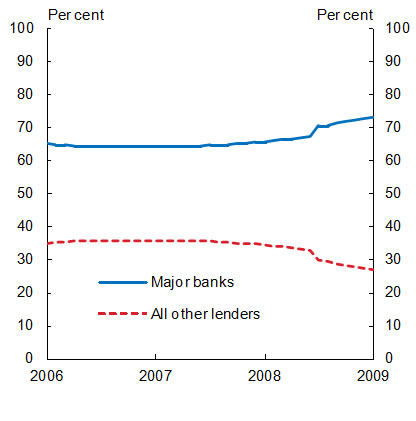

A consequence of these factors is that the four major banks have expanded their collective market share across a range of loan and deposit products.

This is illustrated in the home loan market (Chart 5). The share of total housing loan credit for the five largest banks - the four majors plus St George - has increased from around 60 per cent before the onset of the GFC in mid-2007 to around 73 per cent.

Chart 5: Major banks gain market share

Increasing concentration in the home loan market is not conclusive evidence of a lessening of competition in this segment of the banking sector. Nor, as I said earlier, is the fact of interest rates on home loan products increasing by amounts in excess of movements in the RBA's cash rate.

Yet there is no question that something has changed in the home loan market as a result of the crisis and the downturn in RMBS issuance.

This may not necessarily mean a lessening of competition in the home loan market. The re-pricing of home loans and other lending products could simply be a response to changes in funding costs and a re-assessment of risk.

As far as market interest rates are concerned, the Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia has publically stated that the Reserve Bank Board has taken into account, and will continue to take into account, changes in the pricing of lending products in its monetary policy decisions.

Thus, calls for the Government to regulate lending rates on particular bank products are quite peculiar.

The only certain outcome of any such regulatory intervention would be credit rationing, with some households and businesses finding it impossible to access credit on reasonable terms. Typically, such interventions have unsavoury distributional consequences - for obvious reasons.

The Government is seeking to enhance competitive pressures in the provision of retail banking products, including home loans, with the package of measures announced on the weekend. This includes:

- banning exit fees on new home loans;

- examining providing a capacity for consumers to transfer deposits and mortgages between banks;

- enhancing disclosure of home loan products;

- supporting credit unions and building societies;

- empowering the ACCC to investigate and prosecute anti-competitive price signalling;

- fast-tracking reforms to credit cards;

- monitoring and possibly enhancing ATM reforms; and

- a community awareness and education program designed to make consumers better informed.

International regulatory changes

Finally, I should say a few words about international regulatory reforms. The implementation of these reforms presents a significant challenge for the domestic banking industry and our regulators.

Clearly, the GFC demonstrated severe weaknesses in financial regulation in some markets. It exposed insufficient capital, too little attention to liquidity, incompetence in ratings agencies, and incentives for the executives of some institutions that encouraged inappropriate risk‑taking. It also highlighted weaknesses in accounting standards.

As a response to these issues, the G20 countries (of which Australia is a member) have agreed to implement reforms of the regulatory architecture applying to banks. These reforms are intended to strengthen the global financial system; to reduce the likelihood and severity of future financial crises.

The key reform areas on the G20 agenda are: strengthening the global standards for bank capital and liquidity; addressing the special risks posed by large systemically important financial institutions; and reforming banks remuneration practices. These reforms will be implemented over the next decade.

The Australian Government, assisted by the RBA, APRA and the Treasury has participated actively in developing this reform agenda.

Implementation of these global reforms will enhance the stability of the Australian banking system and reinforce Australia's already robust financial regulatory environment.

In an environment where the Australian banking sector remains heavily reliant on funding from offshore markets, the benefits of implementing the G20 reforms are very likely to outweigh any of their costs.

That said, implementing the reforms will need to be tailored appropriately to take account of Australia's circumstances, while remaining consistent with internationally agreed reforms. It is important that we get the balance right between enhanced financial system stability and the rising costs associated with greater regulation.

Conclusion

Australia's banking industry has emerged from the GFC in a comparatively strong position. Its reputation globally has been enhanced.

But the industry and policy makers face significant challenges relating to the cost and stability of funding, increasing competitive pressures to enhance consumer welfare and implementing international regulatory reforms.

Enhancing competitive pressures in the industry is particularly important. Competition is the cornerstone of efficiency and consumer welfare gains in any market.

But competition needs to be balanced with maintaining stability. A safe and stable banking system is a critical component of the nation's economic infrastructure.

The Government and policy makers look forward to working with the industry to meet the challenges I have raised today, and in implementing the Government's reform package announced on the weekend.

Thank you