Thank you for the opportunity to address you today on taxation reform.

Introduction – the challenge of reform

We live in interesting times, including in the tax world. At one level tax policy can be a rather dry, impenetrable subject, typically the preserve of economists and sometimes accountants and lawyers. But when the topic turns to how the tax system should work in the real world there is intense interest, and rightly so. Tax touches us all personally and there is an intuitive understanding that economic performance is strongly affected by the structure of the tax system. The evidence backing that intuition is now solid and this highlights the need to get the tax system right.

Interest is also heightened now by the prospect of substantial reform of the tax system in governments' (plural) response to the Australia's Future Tax System Review, or as it is popularly called, the Henry Review. The Review has taken place during a period of intense macroeconomic challenge and there are some lessons from the global financial crisis for tax thinking, but this is not the focus of my topic today. Rather, I will talk about some of the long‑term structural issues with the tax system and the drivers of reform, with particular reference to the minerals sector.

The Review is working to propose an agenda for reform that stretches from now into future decades. And it has been a very public policy process, with consultation stretching to "town hall" meetings. A key aspect of the Review is that it is looking at the tax and transfer system, not piece by piece, but with a whole-of-system lens.

The last time there was a whole-of-system review was the Asprey Tax Review Committee Report in 1975. One can make a small observation here on the pace of life these days – the Asprey process took 3 years starting with a relatively simple tax system, while the present review is being done in half that time. This is not to complain – it is a more a comment on the pressing nature of the task at hand. This brings us to the drivers of reform.

Reforms over the last several decades have picked up the Asprey agenda and gone further, transforming the tax and transfer system, with positive consequences for both economic performance and fairness. Australia's tax and transfer system compares well with international comparisons on some metrics. But there are other comparisons which are less favourable and certainly there is a way to go compared with community aspirations. To illustrate, the tax system is too complex with too many taxes – as Ken Henry has put it, the system is "not of human scale". We have taxes on mobile investment that are under competitive pressure as global tax rates fall. There are significant tensions in the federal tax structure due to fragility in some tax bases and costly distortions created by numerous narrowly based taxes at both the Commonwealth and state levels. More broadly, there are notable problems with equity in some tax bases and distorting economic effects in others.

Perhaps we could continue to live with this system but the need for reform is amplified by profound economic and social challenges that raise a question about the system's durability and appropriateness. Each of the following is a full topic in itself and today I am going to do no more than flag three issues.

Firstly, we have a looming aging of the population – right now is the demographic "sweet spot". Over the next 40 years, the number of people of working age will halve relative to those 65 years or older. This will push up expenditure and place pressure on the workforce, economic growth and our capacity to raise revenue from the existing tax base. Policy responses, including in the tax arena, that affect Australia's demography, boost workforce participation and lift productivity can help to offset this fiscal challenge.

Secondly, the system could be better placed to help deal with some environmental problems and address other instances of market failure, particularly in the transport sector.

And thirdly, capital mobility is growing as globalisation proceeds and this will place growing pressure on taxes that apply to mobile investment.

The decades ahead also present several opportunities that considerably strengthen the case for change. Principal among these are the opportunities provided by new and emergent technologies to make greater use of user charging and to improve how governments and citizens interact. And the shift in the centre of gravity in the world economy towards Asia is adding considerable value to our natural resource wealth.

The Review is looking for ways that a better tax system can contribute to a policy solution and, more broadly, position Australia well to meet the challenges of the coming decades. Broadly speaking, the Review is settling on a vision that governments should concentrate revenue raising on a small set of robust tax bases that are minimally distorting, correct for market failures and support workforce participation and productivity. The primary focus is to design what the tax system should look like, rather than closely crafting the next step in reform from our current starting point.

The MCA itself has seen the review for what it is. The MCA submission to the Review Panel was one of the relatively few that picked up and ran with the big picture issues and you should be congratulated for that.

Resource Taxation

For the remainder of this talk I want to focus on some issues that are particularly relevant to the minerals sector, those of royalties, the general issue of company tax and how they are linked.

The main ways that returns to the minerals sector are taxed or shared with the community is through the various royalty and excise regimes, the company tax and, in the case of offshore petroleum, the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax (PRRT). I say shared because as the MCA quite properly points out in its submission the right framework in which to analyse resource taxation is to see resource development as a partnership or joint venture between private capital and community owned resources, where the state is acting as agent and custodian for the community. So, resource royalty arrangements are in effect a way of pricing the use of the community's non‑renewable resources. The MCA has advocated a shift in the royalties regime away from payments linked to volume or revenue to payments linked to profits. One variant of a profits based tax is the so-called resource rent tax.

One point of language needs to be cleared up. When economists talk of "rent" we do not mean all profits, but only part of profits. Specifically, rent means that part of profit which exceeds the risk adjusted required return on capital – in other words, "super-profits". This economic language goes back to one of the founding fathers of economics, David Ricardo, writing 200 years ago. So, if an economist really wants to confuse you with jargon they will use the term "Ricardian rent". Actually, it is not so complicated because it is broadly equivalent to the business term "value creation".

While calling for reform, the MCA has understandably flagged that reform "must not be an unwarranted, short-term or unfair revenue grab" lest it raise sovereign risk concerns. The MCA has also called for a reduction in tax in the form of a lower company tax rate.

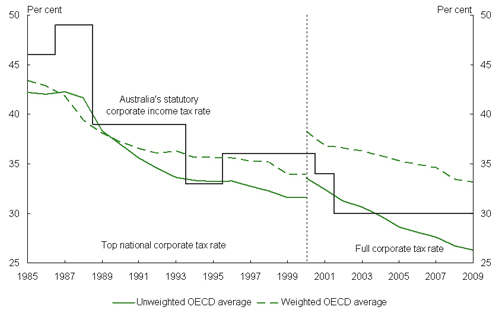

Let us start with company taxes. The first chart shows the evolution of the company tax rate in Australia compared with other OECD countries. There has been a trend across OECD countries to reduce statutory company tax rates. This has been most pronounced in small to medium sized economies. While this trend might slow in the short term because of the global financial crisis, it could reasonably be expected to continue in the long run. In 2001 Australia had the 9th lowest statutory company tax rate in the OECD, by 2009 Australia had moved to the 22nd lowest.

Chart 1: Falling statutory company tax r

ates

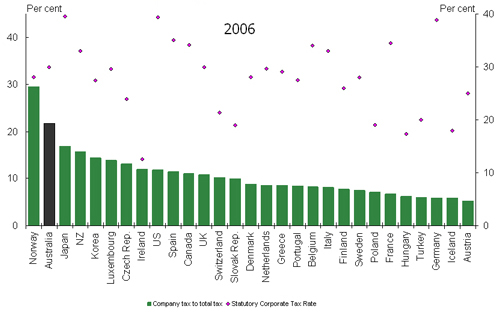

The second chart shows the share of company tax in overall tax revenue compared to other OECD countries. The chart also shows the statutory company tax rate for each country. The comparison of these two charts is stark and it tells an important story. At the broadest level, while Australia's corporate tax rate is not high within the OECD grouping, our share of company tax is high, and second only to Norway. The key question is why?

Chart 2: Share of company tax to tax revenue

There are many factors which have an influence on this measure, including our imputation system and the fact that we do not have social security levies, but I don't want to dwell on these. More important is the fact that the share of national income that is accounted for by the corporate sector is relatively high. You may have noticed on the first chart a hint about what was going on. The two countries on the left are Australia and Norway and there is one notable similarity between our countries – that is the significance of the resource sector.

In Australia, the mining industry alone accounted for around 11.7 per cent of total company tax revenue in 2006‑07 based on the most recent publication of Taxation Statistics. It is expected that the mining industry's share of company tax revenue increased in 2007‑08 and 2008‑09, but will decrease in 2009‑10 given the fall in commodity prices. If we were to go back in history to before the recent commodity price boom the resources share of company tax was 8.0 per cent in 2003‑04. So, the application of the company tax to the resources sector has acted as a de facto resource rent tax. I will come back to this point at the end.

In the resource sector, supernormal profits or rents can persist in the long run because of the finite supply of non-renewable resources or location factors. It is in everyone's interest, both private participants and the community, that long run rents from the resources sector are maximised.

Although this should be obvious, it turns out to be important to keep this in mind when examining resource royalty arrangements because the different ways that resources can be taxed can affect the level of rents. As well as these efficiency issues, an evaluation of resource taxation should also consider revenue raising potential and administration and compliance costs.

There are essentially three royalty mechanisms that can be used to tax resources: a rent‑based tax; a profit‑based tax; and an output‑based royalty. All three are used in Australia.

Under a rent‑based tax, the government collects a percentage of the rents associated with resources by taxing a measure of rent such as either net cash flow or income exceeding an allowance for the normal return.

Under a profits‑based tax, the government collects a percentage of profits by taxing a measure of income.

Under an output‑based royalty, the government collects either a percentage of the value of production – an ad valorem royalty - or a charge per physical unit of production – a specific royalty.

Over time we have seen a shift from specific volume-based royalties to the relatively more efficient ad valorem royalties. In the case of offshore petroleum production, for which the Commonwealth is responsible, the shift has been more marked. A flat per barrel crude oil excise was introduced in 1975, then replaced by progressive rates of excise based on the value of total production from a field and then, since 1987, the PRRT.

An efficient tax is one that does not distort decisions about investment and production where the market is capable of maximising the value of the resource stock for society. Specifically, this means that the tax should not make a marginal project, which was economically feasible before tax, become unviable after tax. It also means that the tax should not distort investment toward less risky investments. Regrettably, very few taxes are efficient and it is very hard to make them so. In general output based taxes are least efficient, profits based taxes more so and rent taxes most efficient. But, the more efficient these taxes are the more complex they are as well.

The purest, most efficient form of a resource rent tax, much beloved in economic models, takes the partnership between private capital and the state to its logical conclusion. In this world, the state will pay to the private partner a share of the up-front development costs of a project, as determined by the rate of rent tax, and the private partner will pay tax to the state only when the project is cash flow positive and has recouped all up-front outlays and a return on capital above normal profits. Before we all get too excited at that prospect, it should also be noted that, in these pure models, the rate of resource rent tax is 100 per cent. If we take a step back from there, a lower rate of tax can be justified because private firms contribute their expertise and that helps to increase the overall creation of rent. Moreover, real world resource rent taxes generally do not perfectly risk share between the private partner and the government.

By way of comparison, under a profit-based tax and an output-based tax the government clearly does not contribute its full share of the cost compared to the rent tax ideal. This is clear for an output-based tax which is levied irrespective of the cost associated with production. But this is less clear for a profit‑based tax. Under a profit-based tax, the government only contributes its share of costs by means of allowing tax deductions when a resource project is in a profit position, but does not compensate investors for the time value of their upfront investment and the risk the government will never contribute its share if the resource project fails. As the government does not contribute to the cost under a profit-based tax and an output‑based tax, both arrangements lower investment and production, and bias investment toward resource projects with a shorter lead time for cost recovery and projects with less risk of failure.

So what does this mean? There are two observations that should be made about profit‑based royalty and output‑based royalty arrangements. First, mines with discovered deposits will produce less output and close earlier than they would in the absence of tax. Second, there will be more undiscovered deposits than there would in the absence of tax. As a result, both arrangements lower the value of resource rents available for the community compared to those available under a resource rent tax. This means that the government not only gives away a slice of the pie but may also end up shrinking the pie itself.

Let's move on to the other two criteria – revenue raising potential and administration and compliance costs.

In one sense these are simply stated. An output or revenue based royalty will collect revenue at an earlier stage in a project life, a profits tax will come in later and the rent tax last of all. One's view on that may depend on whether you are a taxpayer or a government and the level of government as well.

Compliance costs can be least for a profits‑based royalty, particularly if it is built on top of the company tax system. However, this raises tricky issues for what is a resource extraction activity and what is not (say refining) and it becomes very difficult for diversified companies. For this reason most resource taxation is generally based on a project by project treatment be it royalties or rent taxes.

Perhaps the more important issue for both sides of the partnership is the flexibility of th

e tax mechanism to collect a reasonable share of the resource rent under a range of future market outcomes. This is also in the interest of private investors who would benefit from the lower sovereign risk associated with a tax system that is more stable because it collects a constant share of the resource rent under varying economic conditions.

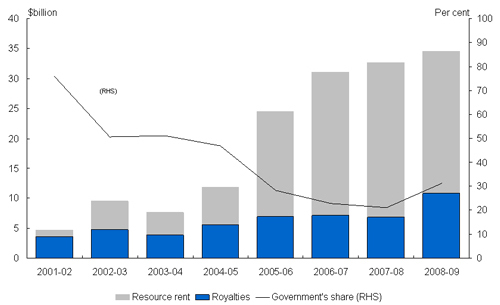

Sovereign risk is the risk that investments will be reduced in value by future changes in government policy. Arguably, there is higher sovereign risk under output‑based royalty arrangements because governments have an incentive to make ad hoc adjustments to royalty rates – mostly upwards – in response to changes in profitability. We have seen this happen in the last financial year with state royalty payments nearly doubling.

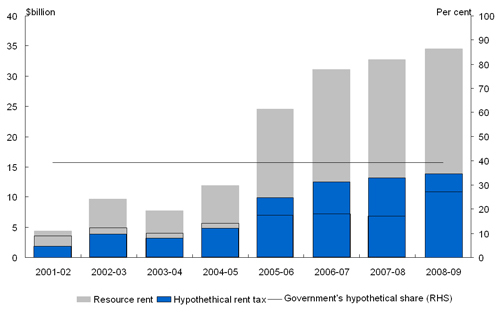

Conversely, a resource rent tax is "automatic" – revenue rises and falls with profit – and it is likely to be more stable because the government would collect a constant share of the rent over various economic conditions.

This next chart shows what has happened to royalty payments over the last cycle and it also shows a comparison of what would have happened under a hypothetical resource rent tax levied at the PRRT rate for illustrative purposes. The chart shows that the government's share of resource rents would have remained constant rather than fluctuating as economic conditions varied.

Chart 3: Royalties - inefficient and unresponsive

Chart 4: Rent tax - efficient and responsive

That is a brief overview of the ways the community can collect a return for its resources.

Looking to the future, the MCA in its submission put forward a preferred position for a future royalty regime based on profit, or a rent tax, rather than output‑based tax on value or volume. You will have gathered with what has been already said, that I have considerable sympathy with that view and it would be consistent with the trend internationally.

Of relevance in considering any move to a different regime is the MCA and its members' desire for certainty going forward. The view is that large investment decisions have been made based on the existing fiscal settings and changing those settings 'for the worse' should not be contemplated as it alters the economics of existing projects. Moreover, changes made in that fashion damage our sovereign risk reputation.

Recent announcements in the petroleum industry where the PRRT applies suggest that Australia's sovereign risk reputation is not a barrier to significant investments. Nevertheless, governments undoubtedly need to consider this issue seriously.

It is also relevant to recognise that governments also make decisions that favour existing investments. I cannot recall anybody arguing that then existing investments should not have been able to access the reductions in the company tax rate in the early 2000s.

There are arguments that the taxation of resource rents in Australia can be improved. However, there are many considerations involved in designing any change, including how arrangements fit within the federal tax system. In discussing the state tax issue, Ken Henry posed three threshold issues for taxation in a federal system: which level of government is responsible for the design of the tax; which level of government is responsible for administration and collection of the tax; and which level of government receives the revenue raised by the tax. For any given tax, the answer to these questions need not be the same and the time has probably come to ask them again of resource tax arrangements.

I noted earlier that the company tax has been acting as a quasi-resource rent tax in recent times. While arrangements for resource taxation might be able to be improved it is difficult to argue that the overall taxation of resource rents should be wound back. The Australian community expects, and should expect, to receive a fair return from its natural resources. So, a key message today is that company taxes and the taxation of resource rents are closely linked. This means that any changes to either arrangement need to carefully consider the interactions with the other.

As it formulates its final recommendations, the Review Panel is balancing considerations about efficiency, sovereign risk, competitiveness and how we can ensure Australia gets a fair return from its abundant natural resources.

Once again thank you for inviting me to speak to you today.

This speech was originally posted on the Australia's Future Tax System website.