Downloads

1. Tax reform: what is happening?

The Government has announced that a tax white paper will look for ways to make taxes lower, fairer and simpler. These are not new goals. Numerous tax reform processes since the Asprey Review in 1975 have had similar aspirations.1

This review has the whole tax system within its scope and will provide detailed reform proposals.

To improve the prospect of identifying proposals which are acceptable to a large proportion of the community, the Government needs a clear understanding of community views about tax. This understanding will be deepened through the release of a discussion paper.

The discussion paper will aim to stimulate a national conversation about tax reform by identifying issues associated with the existing tax system, potential reform opportunities and associated trade-offs.

Successful consultations necessarily involve a period of ambiguity as various reform options are considered. This allows the analysis of reform proposals in a thoughtful manner. Such a process is more likely to deliver feasible reform proposals than the approach of quickly ruling changes in or out.

As the Treasurer has made clear, the discussion paper will be followed by a green paper outlining reform options and then a white paper setting out the Government’s reform package.

With this process in mind, today I will consider why the current economic backdrop means that tax reform is desirable. I will also reflect on company tax both in Australia and overseas.

2. The economic backdrop

As is well known, Australia has enjoyed more than two decades of economic expansion. Our expansion has been largely underpinned by productivity growth associated with technological advancement, the reform agenda of the 1980s / 1990s and, more recently, strong growth in the terms of trade driven by the resources sector. This has sustained growth in national income per capita at an average of more than two per cent per annum.

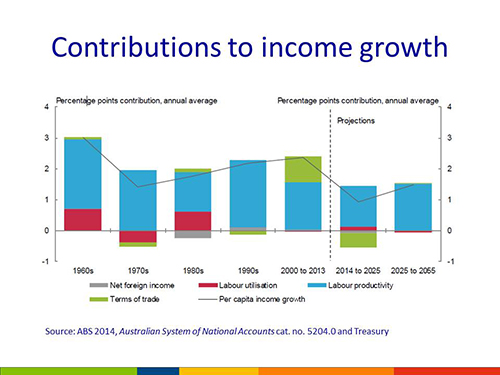

As you can see, this slide shows the sources of our national income growth over the past five decades. Productivity growth has played the leading role in increasing our prosperity. However, as the slide makes clear, challenges are ahead.

Indeed, continuing this performance may not be easy.

Global conditions are relatively challenging as the economy continues its struggle to bounce back from the global financial crisis. The IMF has once again downgraded its outlook for global growth and now expects growth of 3.5 per cent in 2015 and 3.7 per cent in 2016. While the US is a bright spot, the EU and Japan are battling weak demand and soft inflation and China is navigating its challenging transition towards a more balanced and sustainable growth model.

Against this backdrop, the Australian economy is in the midst of a transition from mining investment to broader based drivers of growth. Real GDP grew at 2.5 per cent in 2014 and is expected to remain below trend rates in the near term, as the hole left by the fall in mining investment is significant and difficult to fill completely.

However, fundamentals are in place to support a recovery in the near term. The reduction in oil prices, the fall in the Australian dollar over the past couple of months and interest rates at historic lows should support consumption and demand, particularly in export-oriented and import-competing sectors.

Sustaining growth in the national income over the longer term will also involve significant challenges. As the Intergenerational Report has noted, Australia’s ageing population is likely to push down the participation rate. The report projects that the number of people of working age (16–65) for every person aged 65 and over could decrease from 4.5 people today to 2.7 people in 2055.2 Accordingly, spending on health and pensions is forecast to increase significantly, while a smaller proportion of the population will be of working age.

This economic context raises questions about how to sustain growth in national income.

3. Company tax reform as a driver of productivity growth

If properly implemented, tax reform can drive productivity growth and assist the sustainability of the budget.

How the Government raises revenue affects economic growth. Taxes change relative prices and therefore influence the decisions of individuals and entities. But let’s be clear, taxes have negative consequences for economic growth.

These costs to economic growth can be measured as the “marginal excess burden”, being the cost to the economy of raising an additional dollar of revenue by way of a particular tax.

We could boost productivity growth by considering how the tax system could be weighted away from taxes which have relatively high marginal excess burdens. Our company tax is such a tax.

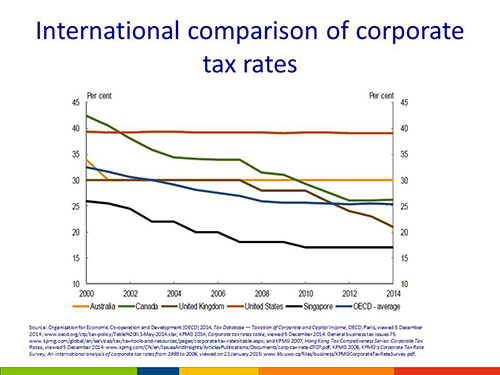

As you can see from the chart, Australia’s company tax rate is high by global standards, particularly given that many other countries have substantially reduced their corporate tax rates:

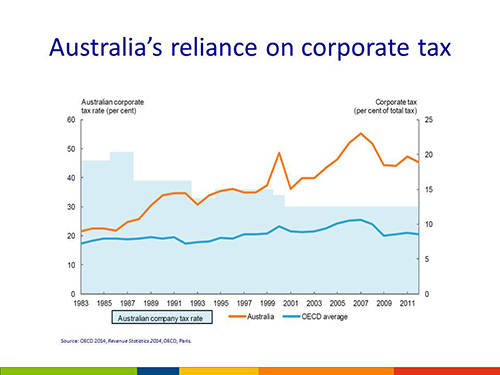

With this higher rate of company tax, Australia has a much greater reliance on company tax than comparable jurisdictions:

So, you might ask, what are the consequences of having a high company tax rate?

High company tax means that Australia loses economic value because some investment opportunities become unviable. This is a particular issue for an open, capital importing economy such as Australia’s, where the investors, especially foreign investors, can easily decide to allocate their capital to opportunities in other jurisdictions.

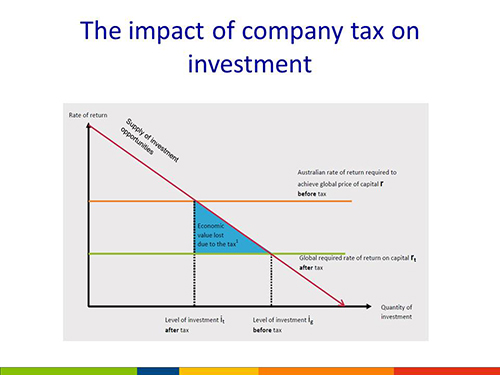

This chart shows the economic effect of company tax.

The red line shows the supply of investment opportunities in Australia. It is downwards sloping, reflecting that there are fewer investment opportunities that will deliver higher rates of return. It is assumed that capital will be allocated first to the projects with the highest rates of return and later to projects with lower rates of return.

The chart assumes that the global required rate of return on capital is a fixed amount (the green line, rt).

Investment will continue until capital has been allocated to all investments which equal or exceed the global rate of return on capital after tax. This point is shown as ig on the chart.

If there were no company tax in Australia, a greater proportion of investment opportunities would be funded. This level of investment is shown by the point ig.

So now we come along and impose the company tax.

This tax makes some investments uneconomic and therefore economic value is lost. This loss is shown as the blue shaded area.

The imposition of company tax means that the total amount of investment in the economy is lower (shown by the move from ig to it) than it would be if there were no company tax.

Now, some caveats. Can all investments be neatly mapped like this? Of course not. But for this story to be broadly true, what do we need?

Firstly we need fewer investment opportunities with high rates of return and more investment opportunities with lower rates of return. Second we need foreign investors who have a profit motive and third a tax that

broadly taxes company profits.

And we have all these.

So, a higher level of investment should increase the capital available for existing labour (ie capital deepening) and thus increase labour productivity. This should, in turn, increase the demand for labour and consequently raise wages and consumption. Therefore, reducing company tax increases the prosperity of Australian workers.

So, what are the problems?

Well, while a reduction in company tax will attract additional investment capital, it will also provide a windfall gain for existing investments, which were funded on the assumption of a higher company tax rate.

This does not apply so much to projects funded by domestic investors, because Australians are still taxed at their marginal rate on company dividends through the imputation system. However, existing foreign investors would receive the windfall gain. If investors repatriate this gain, the Australian economy does not benefit.

Reducing the company tax rate would also, of course, reduce tax revenue in the short term. In the long term, the decline would be partially balanced by increased economic activity derived from additional capital investments. Analysis by the UK Treasury concluded that between 45% to 60% of the cost to revenue of a company tax cut will eventually be offset by increased economic activity.3 But this has long lead times. And what happens in the meantime? This is a matter for the white paper.

4. Tackling base erosion and profit shifting

Another benefit of having a lower company tax rate is that it is likely to decrease the incidence of Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). BEPS arises from the interaction of different tax rules which allow profits to be shifted away from the countries where the profit creation is occurring to a lower taxing country. This can lead to low taxation or even no taxation.

BEPS is becoming a greater issue due to the rise of the digital economy, which means that business activity is becoming more and more mobile. It is now easier for large businesses to move economic activity and value from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. In some instances, these transfers are legitimate, but in other instances it appears that they may occur with the purpose of minimising tax obligations.

BEPS is a concern for many countries, including the United States, where various reforms are under consideration. The risk of BEPS is even greater for a small, open economy such as Australia’s and as a consequence, we have been closely involved in the G20/OECD BEPS Action Plan which is designed to reduce opportunities for companies to engage in this form of tax avoidance.

The G20/OECD Action Plan is based on the principle that companies should be expected to pay tax in the jurisdiction where the economic activity associated with the generation of a profit occurs. The Plan includes measures such as:

- reducing the potential for exploitation of cross-border mismatches in the tax treatment of financial instruments;

- strengthening regimes applying to controlled foreign companies; and

- strengthening transfer pricing rules.

Overall, detecting BEPS can be highly complex. Accordingly, it is difficult to know the extent to which BEPS is affecting our corporate tax base. It may also be that BEPS is more of an issue in sectors where companies have significant intangible assets than sectors such as the mining industry, where large parts of businesses are immobile.

Australia already has strong anti-avoidance measures in place to reduce the risk of BEPS. It is important to note that there are practical limits to enforcement measures – if our regulatory response is very complex and leads to high compliance costs, we may discourage foreign investment which would lead to lower living standards than would otherwise be the case.

One way of dealing with BEPS may be an expectation in the community that large businesses voluntarily disclose the amount of taxes and royalties that they pay in each country – I note that a number of our major mining houses have adopted this approach.4

5. Conclusion

As I said, the Government is undertaking a comprehensive reform of the tax system, with the aim of delivering taxes that are lower, simpler and fairer. This will be done in parallel with the ongoing work on BEPS.

The first step in this process will be the release of a discussion paper. I encourage everyone to engage with the paper so that the Government can gain a deeper understanding of your perspectives and priorities. This will be of major assistance in our ongoing work to deliver a better tax system.

1 Asprey, Lloyd, Parsons and Wood 1975, Taxation Review Committee – Full Report, pages 12-16.

2 Australian Government 2015, Intergenerational Report: Australia in 2055, page viii.

3 HM Revenue and Customs and HM Treasury 2013, Analysis of the dynamic effects of Corporation Tax Reductions.

4 Rio Tinto 2014, Taxes paid in 2014, viewed on 17 March 2015; BHP Billiton 2014, Value Through Performance: Sustainability Report 2014 page 52, viewed on 17 March 2015.