Thank you Dr Heather Smith for setting the scene so clearly.

I am Meghan Quinn, Deputy Secretary of Macroeconomic Group at the Australian Treasury.

On behalf of the Australian Treasury, I would also like to welcome you to this year's Global Forum on Productivity Conference and extend a special thanks to those who have travelled.

Looking at the calibre of our presenters and the large number of you here today, it is clear that increasing productivity is of significant interest to academics and policy makers around the OECD.

And, so it should be. As Dr Smith noted, productivity remains the driving force behind sustained welfare improvement.

But at the same time, productivity remains a somewhat mystical and intangible element of economic analysis.

In fact, the economics of productivity is becoming even more intangible as technology makes capital deepening and multifactor productivity more difficult to measure and understand.

For example, in Australia the share of intellectual property products in new business investment has increased from around 9 per cent in 1990 to around 17 per cent in 2018.

As economists and policy advisers, we continue to strive to understand productivity including: how to measure it; how policy can support it; and how it resonates through businesses structures to workers and our communities more generally.

That's why this forum is so important.

We can build on what we learnt from the 2018 conference in Ottawa, which is that the acceleration of technological progress in the past five years has not yet translated into a broad-based increase in firm productivity and worker wage growth.

Technological improvements are increasingly embodied in final outputs and increase consumer wellbeing, but have not yet transformed production processes as much as expected.

Through this conference, we seek to understand how to deliver the broad-based increases in living standards we all would like to see.

We want to see what is possible through complementary investments in human capabilities and soft skills, and policies to enhance market dynamism so it can keep pace with technological advances.

And today, I would like to focus my opening remarks on technological change and the work we are doing at Treasury to understand the drivers of productivity and also gauge the economy's strengths and where there may be room for improvement.

Productivity in context

Australia is in its 28th year of continuous economic growth. Our experience shows that proactive policy action will help keep our economy on the right path.

But we can't be complacent, particularly in the face of economic headwinds here and abroad.

As set out at the G20 meeting in Fukuoka a few weeks ago, there are real challenges facing firms and workers in our uncertain times.

Investment confidence and business strategies are being challenged by trade tensions and by concerns around the pace of technological change as well as the access and pricing of technology.

Policy makers in Fukuoka highlighted the need for Australia and other nations to redouble efforts to ensure our economics are resilient and flexible. This will require a particular focus on delivering productivity-enhancing structural reforms.

After all, it is widely acknowledged that stabilisation policies, for example monetary policy, which focus on supporting demand growth through consumption and investment, need to be complemented by policies that lift potential economic growth - the supply side of the economy.

So, there is an increasing focus on the most difficult to pin down element of economic growth: productivity.

Better understanding productivity drivers

At Treasury we are investing heavily in our capabilities and access to data to better understand the drivers of productivity growth in Australia.

We know from OECD and other academic research that we need to look beneath the surface to understand the dynamics of a complex system like the economy.

Aggregate macroeconomic data can help identify a problem but it doesn't always tell us the cause of the problem nor where specifically to start looking for solutions.

Increasingly, we're using firm-level or microdata to complement our aggregate data, which allows us to follow workers and firms over time and offers additional insights into how our economy is operating.

We have been and are continuing to invest heavily in our microdata capability.

This year Treasury has collaborated to build Australia's first longitudinal matched employee-employer dataset for policy analysis purposes.

We are also leading a cross-agency effort to improve microdata access for researchers so they can build the evidence base that will supply the next wave of structural reform.

Productivity challenges

Recent Treasury research drawing on microdata shows that Australia faces similar productivity challenges to those of other economies.

Australia's recent aggregate productivity growth has averaged 1.1 per cent per year over the past five years — better than the OECD average of 0.9 per cent. But like other developed nations our aggregate productivity growth has slowed relative to the 30-year average.

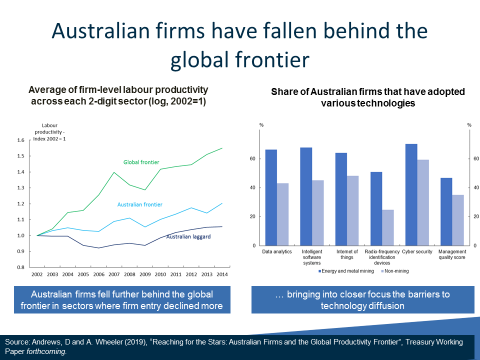

Australian firms have fallen behind firms at the global productivity frontier over recent years.

This slide on the left shows Australian frontier firms' productivity (blue line) improving over the past 15 years, but not keeping pace with the global frontier firms (green line). More troublesome is that Australian laggard firms (dark blue line representing 95 per cent of firms) have barely improved at all.1

This disparity raises the question of how we can increase the diffusion of digital technologies, which is uneven and far from complete across firms.

On the right side of this slide you can see that our energy and metal mining firms - typically operating closer to the international frontier - have been faster to adopt new technologies than firms in other sectors. This is true even for technology that doesn't seem to be that high a priority for mining on the surface such as 'data analytics'.

Mining businesses also have higher management quality scores than non-mining firms. Treasury analysis suggests that labour productivity in the non-mining sector could increase by 6 per cent if managerial practices rose to those in the mining sector.

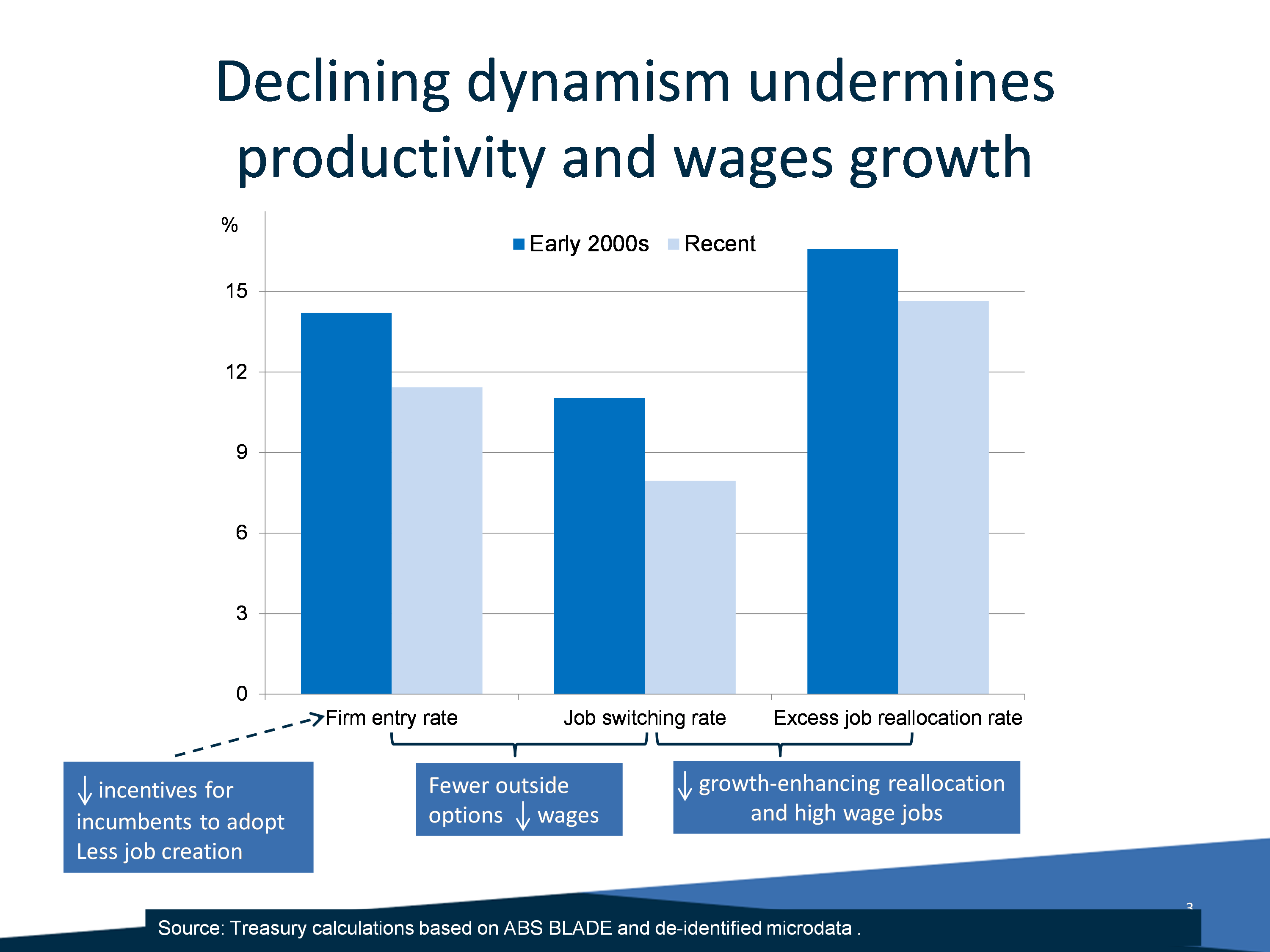

In addition, there are signs that market dynamism has declined in Australia, with knock on implications for productivity and wages.

As mentioned by Dr Smith, the firm entry rate has fallen. The rate of entry for employing firms has declined to 11 per cent in recent years when compared to 14 in the early 2000s.2

Workers are also switching jobs less frequently. The rate of job switching has fallen from 11 per cent in the early 2000s to 8 per cent now and much of this decline appears to reflect a reduction in worker transitions from mature to young firms.

And the more technical 'excess job reallocation rate' - which represents that part of job reallocation (that is job creation plus job destruction) over and above the amount required to accommodate the net employment change - has also fallen by 2 percentage points over this same period.

These results warrant close attention.

We know that a fall in firm entry is generally bad news for job creation and technology adoption.

A fall in job switching means there are likely to be higher costs and risks to workers from moving between jobs and fewer viable outside options for workers. For any given level of employment and unemployment, this would result in less upward pressure on wages.

Treasury research has shown that a 1 percentage point decrease in the job switching rate is roughly associated with a ½ percentage point decline in wages growth.

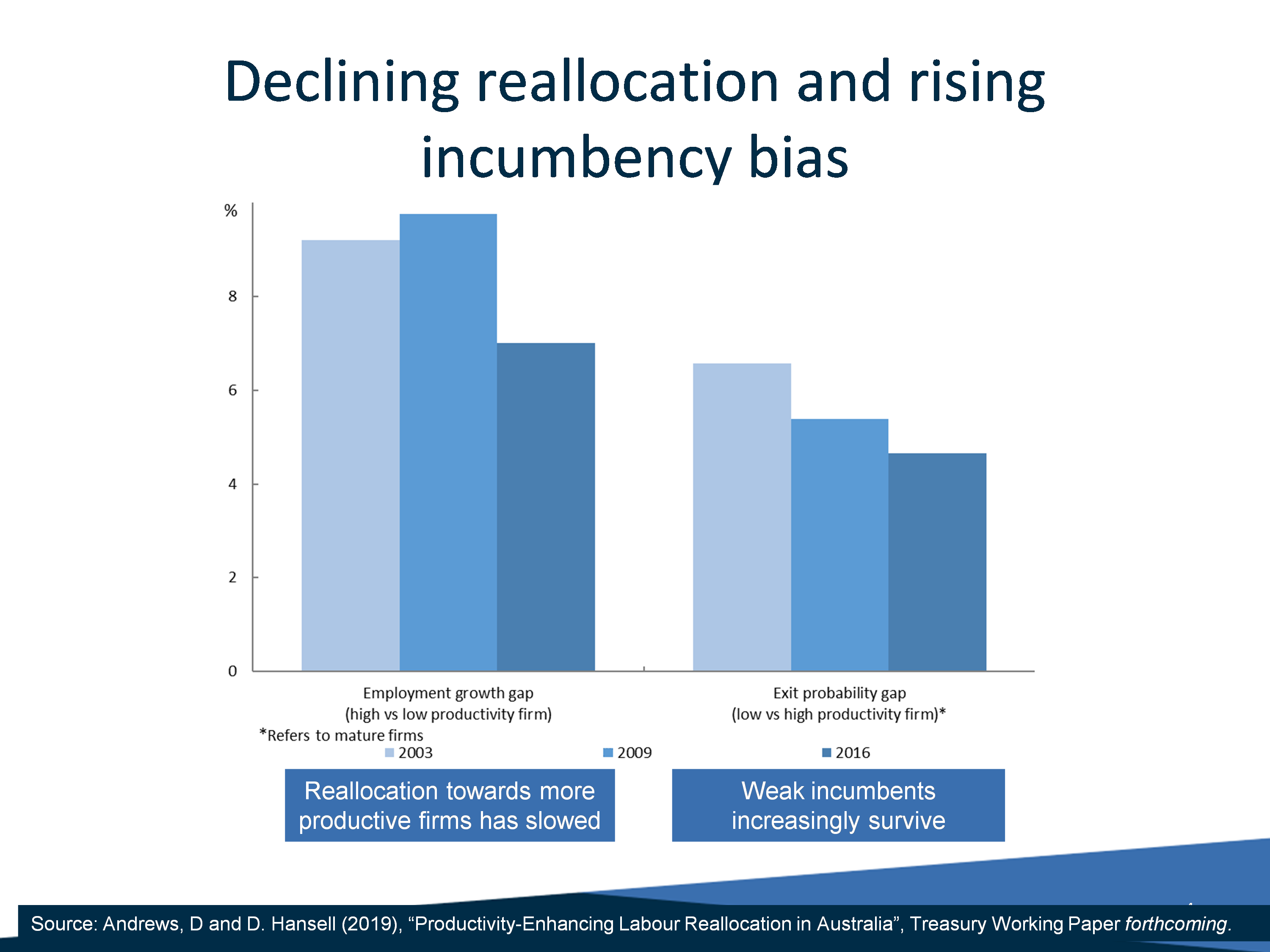

It also appears to be the case that since around 2010 workers are less likely to move to more productive firms.

In particular, the rate at which labour is reallocated from low productivity to high productivity firms has declined by around 2 percentage points since the 2000s, implying relatively fewer higher wage jobs.

Low productivity firms are also increasingly surviving, further impeding resource reallocation to more productive firms.

Capital deepening has also softened, recently reaching the point of 'capital shallowing'. This has been broad-based and is not only related to the end of the mining-investment boom.

This has important implications for Australia as capital deepening has accounted for around three-quarters of labour productivity growth over the past 30 years.

Slower productivity growth concerns are heightened by headwinds facing Australia's income growth from ageing and normalisation of commodity prices.

This analysis suggests that we need community support for structural policies that promote market dynamism. And yet, by their very nature, reforms that support dynamism can be disruptive.

As such, any disruption should be targeted so that it leads to a better outcome over time for living standards. That's why we're also using microdata at Treasury to learn more and understand what happens to people when firms exit the marketplace.

We also need to recognise our economic success in recent years.

Australia has successfully navigated some large economic shocks, including the once in a century rise in commodity prices, and the large movement of people and resources in and out of the mining and construction sectors and across states. We have seen new export industries open up and some structural adjustments in response to technology. All of this happened while Australia continued its growth and avoided undue inflationary pressure or industrial unrest.

This is a testament to our strong economic institutions and strong economic frameworks.

We have seen very strong employment growth - which is one reason the aggregate productivity numbers have looked less healthy in recent times.

Over 670,800 more people are in employment, compared to two years ago. We have seen large lifts in participation in the workforce, particularly among females and older age cohorts.

Overall our employment to population ratio has reached near historic highs of 62.6 per cent. And we know there are large social and economic benefits from more people being engaged in the workplace.

Having lifted the participation and employment rate, we now have the task of ensuring that these jobs are productive.

Lifting productivity is not straightforward and the gains from structural reform are often slow to emerge. In the past, Australia has shown that persistent effort can result in sustained higher productivity growth for a period.

Having had many discussions about productivity, I am aware of its reputation as dry and technical. This might be true, but it's important to build the analytical fact base for policy discussions.

At the same time, we need to remember that this doesn't provide the whole picture. At the level of the firm or the worker, the psychology of change and behavioural factors have a strong impact on decisions and outcomes. Productivity in action is not a dry, technical activity.

As such, the steps for government, business and the community more broadly to impact productivity include building the evidence base for reform; agreeing on priorities for policy; strengthening reform partnerships at different levels of government and among the community; and effectively managing any transitional costs that may arise.

With this in mind, I look forward to learning from international experiences from within the OECD, hearing what others are observing and how these challenges are being addressed. Thank you all for being here to share your experiences.

Lastly, I wish to thank Dan Andrews for his leadership role in the Global Forum on Productivity, the OECD Secretariat and the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science for helping to bring us all here for the coming two days.

1 - Labour productivity at the global frontier is calculated as the average labour productivity of the most productive 5 per cent of firms in each global (2-digit) industry for a given year. As discussed in Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal (2016), these estimates are robust to a range of definitional choices. The Australian frontier corresponds to the average labour productivity of the most productive 5 per cent of firms in each Australian (2-digit) industry for a given year. Australian laggards refer to the average productivity of all other firms.

2 - These estimates pertain to entrants that employ workers. The decline in entry for all firms (i.e. also including those that do not employ workers) is more marked (i.e. up to 5 percentage points), though it has retraced somewhat more recently.