Downloads

Introduction

Thank you for the invitation to speak with you this morning.

The Budget was handed down a little over seven weeks ago now. Since then, there has been much debate on the Government's policies and what this will mean for individuals, businesses, and the economy as a whole.

Today, I would like to recap some of the structural changes happening in Australia, and to provide some context for the Budget as well as other reform processes.

To an extent, these structural changes directly reflect the circumstances and challenges facing your sector – those associated with adjusting to the biggest resources investment boom in our history.

But there are other drivers of major change – the ageing of our population, an evolving and turbulent global economy – that require us to consider what we can and have to change to maintain and increase our living standards.

I will touch on the need for further reforms, and reflect on what we can learn from the past in pursuing reform in the future. Let me begin with a snapshot of the economy.

Challenges confronting the national economy

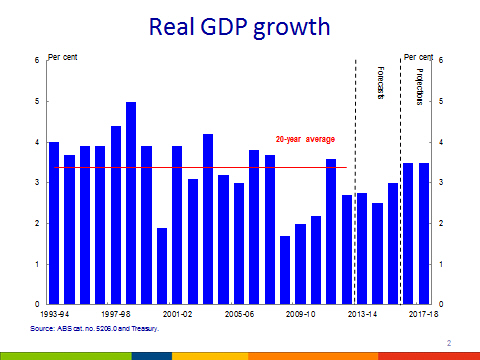

Australia has achieved over two decades of continuous economic growth, and our forecasts suggest the next few years will continue this trend. As a result, Australians now enjoy some of the highest living standards in the world.

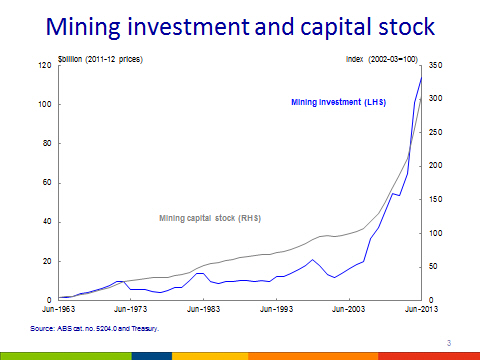

As we all know, the major driver of growth in more recent years has been the unprecedented investment stemming from the mining boom.

To meet demand from our trading partners, mining investment increased from less than 2 per cent of GDP pre-boom to almost 8 per cent last financial year. This has seen the capital stock in the mining sector triple since the boom began. An additional 180,000 workers have been employed in this sector, and many more jobs have been created in related industries.

However, we are now at a critical point in the boom's evolution. Prices for commodities peaked in 2011, and we are likely to have just passed the peak in capital investment.

We now find ourselves moving into another stage of the boom, which features rising production and export volumes, but falling prices and investment. Given the sheer magnitude of the investment boom, the economy will face some challenges in navigating this transition.

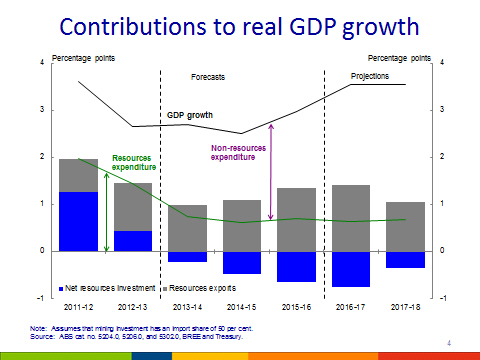

In the short term, net resources investment (the blue bars in the chart) is set to shift from being a major contributor to economic growth to a detractor from growth.

Exports (the grey bars) will rise as completed projects go into production, but the net effect of these two forces (represented by the green line) means that the economy will heavily rely on other sectors if it is to return to trend growth over the medium term.

We forecast that further falls in the terms of trade and subdued domestic price growth will result in nominal GDP growing by 3 per cent in 2014-15 and 4 ¾ per cent in 2015-16, well below the average rate of growth over the past 20 years.

The declining terms of trade will heavily influence the medium term outlook for average incomes.

Despite a significant slowdown in productivity growth, average incomes in Australia have grown at among the highest rates of OECD countries over the past decade. That's largely due to the rising terms of trade and associated appreciation of the exchange rate.

We can no longer rely on rising terms of trade as a source of income growth.

In addition, the ageing of the population will place downward pressure on income growth from increasing workforce participation.

In the medium term, income growth will therefore largely be determined by our success in raising our productivity.

Increasing productivity to achieve the income growth that we are used to will be a significant challenge.

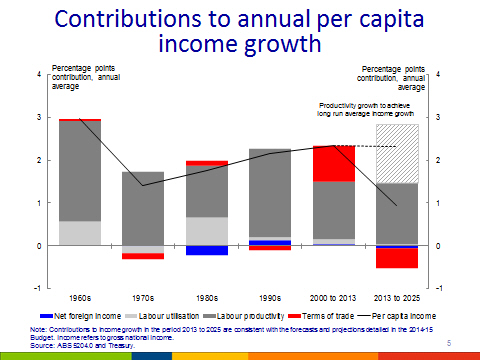

This chart shows the sources of growth in per capita incomes over the past half century, and two scenarios.

- If we assume labour productivity grows at its long-term average, then incomes will grow on average over the decade ahead by around 1 per cent per year, or less than half of the rates to which Australians have become accustomed.

- To achieve average income growth in line with its long-term average, we will need sustained labour productivity growth of around 3 per cent. This is significantly more than in the past and around double what has been achieved since the turn of the century.

So what do we know will affect productivity growth?

The shift in phase of the mining boom will result in a boost to labour productivity as more projects come on line and move towards full production.

The resources sector generates around 16 per cent of Australia's production and this productivity turnaround will therefore have a sizable impact on national productivity. It will not, however, lead to a commensurate increase in incomes because around four-fifths of the resources investment has been funded from offshore.

We also know that continuing structural change in the economy is likely to have a negative impact on the rate of productivity growth.

Already making up more than three quarters of Australia's employment, services sectors are expected to continue to become a larger part of the economy. We expect low productivity growth sectors, such as aged care and health sectors, to expand, with high productivity growth sectors like financial services declining in relative terms.

Over the decade ahead, changing industry structure is projected to detract around 0.3 percentage points from the 30-year average labour productivity growth rate of 1.5 per cent per year.

While these factors present challenges, they also offer some opportunities.

The massive growth of the Asia-Pacific middle class, from 500 million in 2009 to 3.2 billion in 2030, offers opportunities for Australia's export sectors. Being open, innovative and competitive in this environment will allow us to make the most of opportunities for productivity and export-led income growth.

Budget priorities

Let me now turn to the Budget.

Recognising the short-term economic realities, the Government has employed a measured pace of fiscal consolidation, but one that nevertheless seeks to achieve a structural surplus in five years. The Budget also focuses on structural reforms that build fiscal resilience and support productivity.

It is worth noting the distinct philosophical change underpinning Budget measures, one that views government's role in improving living standards as primarily one of supporting the private sector in generating sustained employment and income growth, and providing some of the dividends of that growth – through taxation – to support those most disadvantaged.

It follows that tax burdens should not unduly dull incentives for entrepreneurship and work, and taxation revenue should be used prudently.

A second part of the philosophical shift is the view that the states should be, as the Prime Minister puts it, "sovereign in their own sphere".

Priorities in the Budget, therefore, include:

- Removing impediments and disincentives to work and initiative like subsidies to unviable businesses and poorly-targeted income assistance.

- Expanding the economy's productive capacity by investing in infrastructure and ensuring that it is efficiently planned and u

sed. - Measures to reduce the cost, and improve the efficiency, of government, informed by the Commission of Audit.

- Establishing new funding arrangements with the states to lay the groundwork for considering the future roles and responsibilities of different levels of government.

The Budget also contained the Exploration Development Incentive, which will start from 1 July 2014, and is intended to encourage investment in small exploration companies undertaking greenfields mineral exploration in Australia.

- I understand Minister McFarlane will have more to say on this at lunch.

The Budget also allows for future tax cuts. I will talk more about this in a moment.

Opportunities for reform

Considering the philosophical change underpinning the Budget, and the magnitude of our productivity challenge, it is clear that the Budget is one step in what must be a broader program of reform.

The Government has indicated a willingness to address issues of flexibility and efficiency in our markets – including through the Competition Policy Review, the Productivity Commission review of the Fair Work Laws, and the Financial System Inquiry.

These processes will help the Government identify opportunities to enhance policy settings. They will hopefully ensure that Australia's key economic policy frameworks are suited to the needs of our evolving economy.

In addition to these reviews, the Government has committed to releasing white papers on reform of the tax system and of the federation by the end of 2015, and has said that it will take any proposals for reform to the next election.

It is hard to overstate the need for reforming the tax system. If our public finances are not placed on a sustainable footing, tax reform becomes more difficult as time passes.

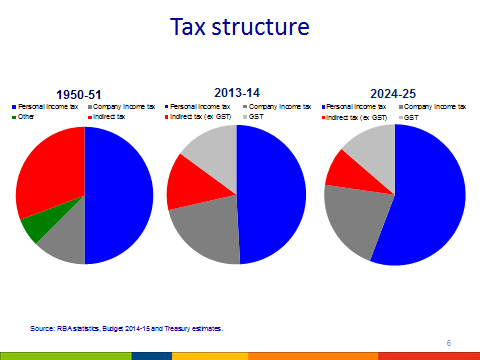

Our tax mix is heavily weighted toward direct taxes on income — personal and corporate. If we were to leave our tax rates and bases as they are, our reliance on income taxes would grow over time.

We will move even further in this direction if, as we anticipate, the relative share of total indirect taxes continues its long-term decline, including the GST. Part of this effect can be seen in the increase in the share of revenue raised from personal income tax (a result of fiscal drag).

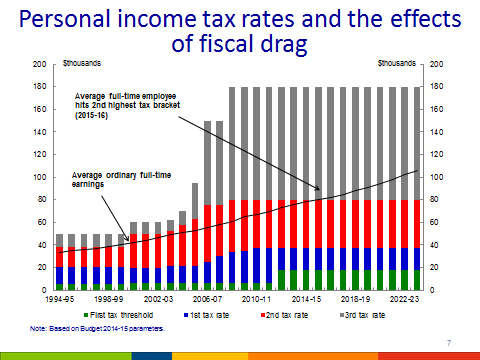

Fiscal drag will pull someone on average full-time earnings into the 37 per cent tax bracket from 2015-16, and will increase the average tax rate faced by a taxpayer earning the projected average from 23 to 28 per cent by 2024-25 — an increase in their tax burden of almost a quarter.

If fiscal drag is not periodically returned in the form of personal income tax cuts, it can reduce incentives for workforce participation at low levels of income, and increase incentives for tax minimisation at higher levels of income.

There are similar implications for corporate income tax. Over recent decades, the clear international trend has been for countries to lower corporate tax rates and broaden bases. The Government has committed to lower the company tax rate by 1.5 percentage points in 2015.

One of the key issues of the reform debate will be the competitiveness of our corporate tax system and our capacity to attract mobile global investment.

The increased digitisation of the economy across all sectors, the rise in corporations that operate across multiple international borders, the increased mobility of capital, and the growing importance of intangibles are all positive economic developments, however they have implications for the tax system.

For one, capital is more mobile and the cost to the economy of trying to tax these profits is likely to be increasing. Furthermore, it is placing pressure on the international tax system.

Work is underway to address these challenges — through, for example, the G20 and OECD work on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting.

In Australia, we have managed these risks by running a pretty tight ship when it comes to integrity measures.

However, the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting work is not a silver bullet, and any further integrity rules will increase complexity and compliance costs.

Without conscious change, the economic cost of raising tax from our current tax mix will increase.

This will not be a simple exercise, particularly in the context of our federation. Considerations for an optimal tax mix are relevant for all levels of government in Australia. And any changes are likely to have implications for the imbalances between state and territory government spending and taxing, as well as for transfers between the states, or to the states from the Commonwealth.

Reform is difficult – but we can learn from the past.

For the community to embrace change in this area, the case for reform has to be compelling and well-understood. There is no magic formula for this. But past experience has taught us some lessons.

Reform proposals should highlight medium-term economic payoffs – the positive impacts they will have on individual effort, investment and growth. This dynamic, forward-looking focus will help guard against the 'zero-sum' – or rob-Peter-to-pay-Paul – focus of recent tax policy debates.

This is not to suggest that equity should be ignored – no reform proposition will gain support if it is viewed as fundamentally unfair. But let me reiterate an important distinction on this point that I made in a forum earlier this week.

It is one thing to argue that reform proposals should be designed with fairness in mind – nobody would disagree with that. It is quite another to invoke vague notions of fairness to oppose all reform.

Using this kind of concept to defend what is clearly an unsustainable status quo means consigning Australia to a deteriorating future.

Put another way, if there can be no losers from any individual element of a reform proposal, even if the aggregate package advances the nation's interest, this makes it virtually impossible to have a sensible debate about policy choices.

A further lesson from successful reform experience is that details matter. Proposals which work in a textbook but fail to recognise commercial realities (particularly in business tax), will eventually be found out.

Their purported benefits may well prove illusory, the costs they impose may be greater than assumed, and they might be difficult, if not impossible, to implement.

This highlights the importance of conducting open and transparent consultation as early as possible in the policy development process.

Taxpayers - whether they are ordinary wage earners, small businesses, or large conglomerates - know far more about how the tax system affects them than anyone else. Reform advocates, both in and outside government, should be humble enough to acknowledge that.

It is therefore important that reforms to our tax system and our Federation be considered together, so that the public debate can, as much as possible, be informed of the complementarities and the trade-offs that will inevitably arise from any proposed changes.

Closely aligning these white papers provides a once-in-a-generation opportunity for engagement, debate, analysis and, ultimately, reform.

Conclusion

Past structural reform efforts were not always popular but they provided the dividends of growth we now all enjoy – indeed we now take them for granted!

We once again find ourselves at a critical juncture where it is through ambitious structural reform, pursued in the national interest that Australians will continue to enjoy high living standards.

Bef

ore us there lie opportunities to undertake holistic assessments of some key policy areas. I encourage you all to take advantage of them.

Thank you.