Downloads

I would like to acknowledge the contribution of Treasury colleagues Shane Johnson and Tim Wong in the preparation of this address.

Let me start by thanking the University of Tasmania for inviting me to give this lecture, which commemorates a truly outstanding Australian — indeed a truly outstanding Tasmanian.

Lyndhurst Falkiner Giblin (1872-1951) and three of his colleagues (James Brigden, Douglas Copland and Roland Wilson) formed a personal and intellectual bond at the University of Tasmania between 1919 and 1924. This was the group that would later be known as 'Giblin's Platoon'.1

The Platoon was pivotal in the shaping of economic thought and policymaking in Australia.

Their intellectual achievements stimulated, and arguably anticipated, the leading currents in contemporaneous economic thinking — even the likes of a certain John Maynard Keynes.

It was this same Platoon that first introduced the economist to Australian public life, constructing a bridge of public debate between academia and policy making.

And all of them, in their various ways, had a major impact on the Treasury. While Giblin himself spent only a couple of years in the department, he was surely its most influential adviser over a long period including World War II, and he recruited others, including Roland Wilson who went on to become the Treasury's longest serving Secretary. Wilson credited Giblin with the founding of Australian political economy.

Some of Giblin's written works exemplify his legacy.

In 1930, Giblin wrote a series of articles in the Melbourne Herald called Letters to John Smith. These letters attracted widespread attention, becoming influential in developing a broad understanding of the challenges facing Australia during the Great Depression. In a series of ten letters, Giblin explained, in simple language, the economic issues facing Australia at the start of the Depression and described a pathway by which the country could find its way back to prosperity.

In Giblin's honour (talk about standing on the shoulders of giants!) I will try, in this short address, to outline some of the challenges facing the Australian economy today and make some remarks on our pathway to future prosperity.

At a time of extraordinary upheaval for Australian society, when the fears of mass unemployment, inflation and economic instability gripped the world, Giblin's ability to explain economic issues clearly and simply proved to be of immense value.

Today, we are again going through a period of unusual upheaval in the global economy: a historic transition in economic power from west to east that, having been in progress for a couple of decades, then accelerated abruptly in 2007-08 with the onset of what we call a global financial crisis; a crisis that, more accurately, would have been labelled a Western financial crisis. That crisis hasn't played out fully as yet. Many globally significant financial institutions remain weak and heavily reliant on government support arrangements. And questions are now being asked about the sustainability in several Western countries, not only of those government financed support arrangements, but of government finance itself.

So I'd like to take this opportunity, in delivering the 2011 lecture in Giblin's honour, to take a look at the nature of the economic transformation occurring in Australia in his time, and consider the relevance of the lessons learned then for us today, in another period of economic transformation.

A perspective on Giblin's Australia

It is impossible to do justice, in a 30 minute address, to the mammoth topic of Australia's economic evolution during Giblin's lifetime. We'll have to do with a rough sketch.

Economic advancement — the rise of manufacturing

The three decades prior to the Great Depression that hit Australia from 1929 set the scene for Australia's economic development through the rest of the 20th century.

Despite the interruption, forced adjustments and price instability caused by the Great War, Australia experienced steady population growth; the uptake of new technologies in areas such as automotive engineering and heavy industry; and increasing openness to foreign investment.

Buoyed by those currents, the manufacturing sector was destined to become one of the most significant performers in the Australian economy in the 20th century.

It had been one of the major beneficiaries of the dismantling of interstate tariffs at Federation. Employment in manufacturing expanded rapidly — almost doubling in the first decade of Federation, rising from around 190,000 to 361,000 people by 1910-11 — accounting for more than 20 per cent of total employment.

The dominant categories of manufacturing during this time included the processing of clothing and textiles, metal, wood, food and drink, and agricultural products.

In the two decades that followed, however, that is the teens and the 1920s, manufacturing only broadly held its share of total employment, despite a number of factors that might have been expected to assist it. These factors included:

- the industrial requirements of war;

- isolation from foreign competition afforded by the war;

- heavy tariffs being imposed to nurture and protect an emerging diversity of domestic manufactures;

- improvements in technology and economic infrastructure; and

- the establishment of large automotive plants to meet a burgeoning demand for motor vehicles.

While statistics about production for the early periods of Australia's history should be read with caution, estimates of manufacturing's share of domestic output in those decades would suggest a broadly similar story to that told by the employment numbers.

While manufacturing as a share of GDP doubled between 1866 (six years before Giblin was born) and 1910 — it only broadly held its share over the period between 1925 and 1930.

What was going on?

Economic advancement — moving to 'newer' more advanced manufacturing activities

Drilling down into manufacturing industry detail yields some useful insights.

What was happening within the manufacturing sector was part of a longer term trend — a 20th century gradual 'changing of the guard' if you like.

While manufacturing's share of output and employment did not substantially increase much in the second and third decades of the 20th century, the composition of the sector changed dramatically. Broadly, more advanced manufacturing activities developed at the expense of the more traditional, lower-value industries.

Processing industries that were relatively intensive in manual labour experienced a long-term relative decline. One reason for this was that wage costs facing producers in Australia were very high relative to its trading partners. During the mid-1920s, coincident with a surge in the terms of trade, from trough to peak more than 130 per cent, Australian wages were 50 to 100 per cent higher than those paid to workers in comparable activities in the United Kingdom.2 Low skills manufacturing was simply uncompetitive; or, to put it in more technical language, the real exchange rate was too high to accommodate continued expansion of these sorts of manufactures. This may have been an early example of a large terms of trade induced real appreciation affecting the structure of the Australian economy.

On the other hand, more advanced, emerging industries like motor vehicles, metals, engineering, drugs and chemicals, were expanding.

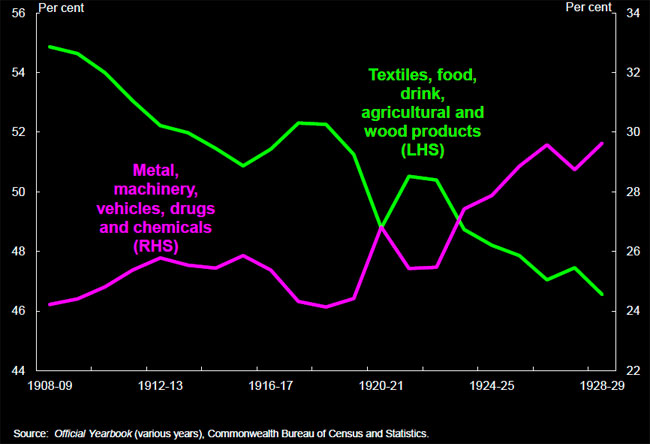

Chart 1: Share of manufacturing employment, 1908-1929

Chart 1 shows employment in selected manufacturing sub-industries as a proportion of total employment in manufacturing between 1908 and 1929. Since the second half of the first decade, employment in more traditional activities [the green line] — the processing of agricultural and pastoral products, clothing and textiles and wood products — recorded a trend decline. In fact, even during the Roaring Twenties, a number of these industries were actually shedding labour, especially those associated with rural exports.

The purple line, on the other hand, represents the 'newer', higher value, industries which took off post war — like motor vehicles, machinery assembly, drugs and chemicals.

While the Great Depression hit these more advanced activities hard,3 they were the ones that led the recovery and the surge in manufacturing's relative importance in the thirty years following.

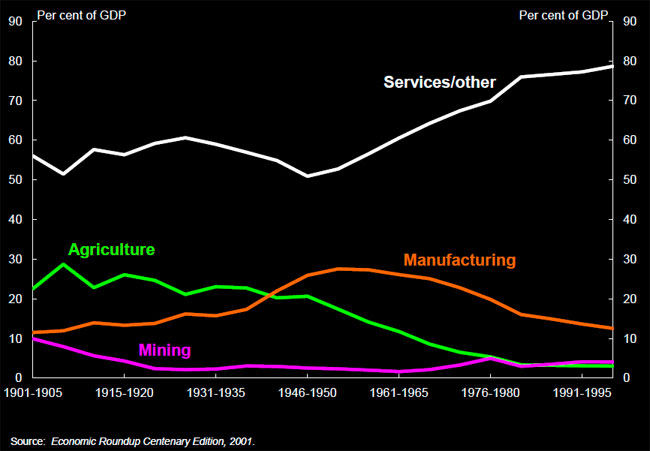

Consider the following chart on industry GDP shares over time [Chart 2].

Chart 2: Industry GDP share, 1901-2000

Boosted by the heavy production requirements of World War II, the 1940s saw manufacturing overtake the traditionally dominant agriculture sector.

In the 1950s and 60s4 manufacturing remained buoyant, while services provided the engines of growth (with economic growth in these two decades some way above the 20th century average). 5 In contrast, primary industries declined gradually as a share of GDP.

Incidentally, this shift had been keenly anticipated by Giblin and Brigden in the 1930s. Through productivity gains and deregulation rather than protection, it was thought that the relative expansion of the secondary industries would absorb more people, lift employment and drive the recovery.6

From Giblin's Australia to the present day

It turns out that the 'changing of the guard' observed in Giblin's time is just one among a large number of historical examples of large scale structural change in the Australian economy. Structurally, this is an economy that has never sat still.

Economic advancement — embracing the trend towards knowledge industries

Just as the more advanced parts of the manufacturing sector overtook primary and lower value industries towards the end of Giblin's life, the second half of the 20th century saw a rise (relative to manufacturing) in the higher productivity, higher value, knowledge based goods and services.

This experience is common to the economic development of virtually all advanced economies over the past half century. The shift towards higher value, including knowledge-based, services has been driven largely by changing tastes and preferences arising from higher incomes, technological change and demographic change.

But the pattern of comparative advantage was also shifting in the second half of the 20th century, as rapidly industrialising Asian nations emerged as labour-abundant competitors.

And the trend toward services persisted, despite the impost of heavy protectionist measures in advanced economies.

There were two key features of Australian protectionism. One was a naïve desire to promote exports, depress imports and shield economies from external fluctuations. This was an argument primarily mercantilist in nature: a protective wall comprised of tariffs, import controls and other regulatory features was considered necessary in order to grow an Australian manufacturing industry and protect the economy from swings in commodity markets.7

The second feature of Australian protectionism arose from a far more considered exposition of trade theory. The Brigden enquiry, 'The Australian Tariff: An Economic Enquiry', was prepared by Brigden, Copland, Dyason, Giblin and Wickens at the request of Prime Minister Bruce. It reported its findings in 1929. The report alluded to many of the insights of trade theory that were popularised subsequently by the Hecksher-Ohlin-Samuelson trade model and, in particular, it foreshadowed the key results of the celebrated Stolper-Samuelson theorem.

The report had three key conclusions: tariffs have costs that can outweigh the benefits; real wages are not necessarily higher under free trade; and the available evidence doesn't allow a more precise statement on either of these two effects.

Today we understand that the imposition of a tariff can increase the real (producer) wage if the import-competing sector of the economy is relatively labour-intensive. This is the standard Stolper-Samuelson result established in 1941. One can imagine the power of the theorem in the early 1950s with movements in the terms of trade advantaging capital-intensive exports, and a concern that slower real wages growth would undermine the pursuit of rising living standards.

In fact, protectionist measures proved unsuccessful in holding back the tide of economic development. It seems likely that they simply shifted the pain of adjustment to those workers and businesses not shielded from foreign competition and hurt consumers generally.

Today, the services sector — capturing many of the new knowledge-based activities, including information and communications, professional, health, finance and scientific services as well as more traditional services like retail, hospitality and tourism — has risen to almost 80 per cent of total Australian output and employment.

Manufacturing, which peaked mid-century, has since declined over time as a share of GDP to a level similar to that at Federation.

This trend is typical of the advanced economies against which we usually compare ourselves.

Chart 3: Employment share by industry and overall education levels

Chart 3 compares employment shares by industry for the United States, the United Kingdom and Japan against education per person employed.

As those employed in services tend to have a higher incidence of post-school qualifications than other sectors, it is not surprising that the services industries (the [orange dashed] line) have expanded with improvements in education levels (the [pink] line).8

In these countries, primary and manufacturing industries, on the other hand (the [green and white dashed] lines), have declined in relative importance in the latter half of the century — following a similar trend to that seen in Australia.

At the risk of gross over-generalisation, it seems fair to say that trends in industrial structure tend to be of long duration and fairly immune to policy intervention – with the probable exception of those policies that affect rates of factor accumulation, including policies affecting education and training, immigration and levels of capital investment.

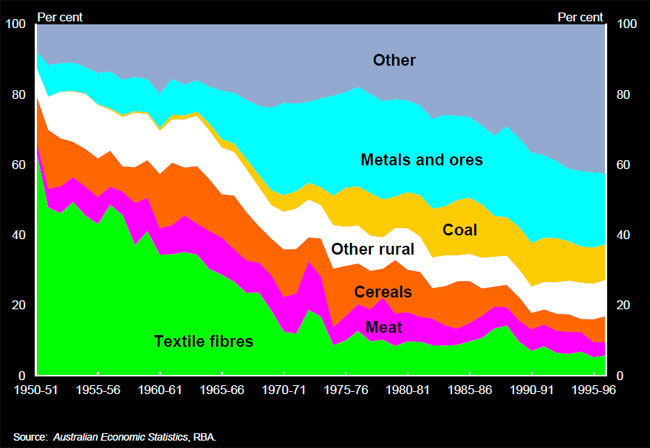

While our industrial structure has shown a marked trend decline in manufacturing and agriculture post-WW2, with flat mining output, trends in export shares have been very different. In the 1950s commodities made up more than 85 per cent of goods exports. Textile fibres — which is predominantly wool — alone represented nearly 50 per cent of goods exports [Chart 4].

Chart 4: Share of goo

ds export

Of course, the large share of resources in Australian exports in the second half of the 20th century reflected our natural endowments. But it was an export performance tied also to the post-war reconstruction and rapid industrialisation of Japan.

The Japanese post-war industrial expansion contributed to strong terms of trade in Australia, and these were taken to extraordinarily high levels in 1951 with the Korean War surge in demand for woollen military uniforms. Asian growth is once again having a pronounced impact on our terms of trade – a matter to which I will return in a moment.

The Australia in which Giblin lived embraced the emerging technologies and industries of his day — the world of motor vehicles, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, engineering and metal industries. Today, there is a case for embracing the emerging technologies and industrial opportunities of the 21st Century.

Technology improvements, particularly in information and communications, will continue to transform the way we do business and the way we live. And they will transform the structure of the national economy — just as the manufacturing sector transformed the economy in the first half of the 20th century.

Technological advancement has opened up new sets of opportunity.

It will continue to bring new and innovative goods and services into the marketplace, giving Australian consumers expanded opportunities and more choice. For producers too there is the promise of expanded opportunity, with new technologies offering opportunities to secure productivity gains through innovation and adaptation.

Those opportunities can be expanded with policies that support flexible education systems; protect financial systems; and reform to taxation systems to facilitate more rapid rates of physical capital renewal and accumulation and a more productive allocation of the capital stock.

Such policy prescriptions would have force in all advanced economies, in which the strongest growth sectors are likely, increasingly, to be knowledge-based industries. But there are features of the Australian economy that distinguish it from most other advanced economies, in which the factors of production are, themselves, largely produced – whether it be manufactured capital equipment or skilled labour 'produced' from unskilled labour in the education sector. Our factor endowments include substantial natural resources. And that peculiarity sets us apart in important ways. Most significantly, it means that we view the re-emergence of the Asian giants quite differently.

The re-emergence of Asia

On numerous other occasions I have spoken extensively about the implications for Australia of the re-emergence of China and India. I will keep it brief today.

The mining boom

The re-emergence of China and Indiahas created a rapidly growing demand for energy and mineral commodities. Global supply of these commodities has expanded rapidly, with some of these doubling in the past decade. Even so, it has not been able to keep pace with demand, and prices have sky rocketed.

With increases in the prices of the commodities we export and falling prices of manufactures that we import, Australia's terms of trade have improved significantly.

The Governor of the Reserve Bank put it quite nicely recently — five years ago, a ship load of iron ore was worth about the same as about 2,200 flat screen television sets. Today it is worth about 22,000 flat-screen TV sets – partly due to TV prices falling but more due to the price of iron ore rising by a factor of six.9

Australia, as a net exporter of resource commodities and a net importer of manufactured goods, is in a prime position to benefit from China's development.

At some point, growth in the global extraction of commodities like coal and iron ore should start to outweigh continued strong growth in global demand, driving down prices. But nobody knows when, or by how much.

My view is that a reasonable case can be made for considering that the terms of trade will remain significantly higher, on average, over the coming decade or two than they were before the start of the mining boom.

Over the past decade, jobs in mining and construction have almost doubled, from around 750,000 to around 1.3 million. Employment growth in mining has grown by 8.6 per cent a year for the past five years, compared with 2.4 per cent across the non-mining economy. Even so, most of the growth in employment has been in construction rather than mining per se. Over the same period, manufacturing has lost roughly 50,000 jobs, down to around one million people employed; its share of the workforce dropping from 12 to 9 per cent.

The mining boom seems to have accelerated a long-term adjustment away from manufacturing. But it would be a serious mistake to forecast the death of Australian manufacturing. That industry has a track record of remarkable resilience and adaptability — just as agriculture adapted to industrialisation and changes in global markets in the 20th century.

As Australia's tariff barriers came down in the 1980s and early 1990s, our manufacturing sector successfully shifted its focus away from products in direct competition with low cost producers, to higher value-add manufactures.

More recently, manufactures for the domestic resources and construction sectors have grown strongly. A substantial decline in output for industries like textiles, clothing, wood and paper products has, to some extent, been offset by a shift into manufactures related to mining and construction. This trend might be expected to continue for some time.

A burgeoning Asian middle class

At other times in our history we have witnessed some of the opportunities that income growth in emerging markets presents for Australian exporters.

Consider tourism services, for example, and the strong Japanese demand that drove its development. With increased demand for tourism services from emerging markets, there is considerable potential to attract a greater share of increasingly wealthy travellers to Australia for business tourism, holiday packages and to visit family and friends.

According to the United Nations World Tourism Organisation, the number of international tourist arrivals globally reached 935 million in 2010. That's an increase of 58 million, or seven per cent, from 2009. Emerging economies continue to drive global outbound tourism expenditure growth — for example, 17 per cent for China in 2010 — outstripping growth in traditional markets like Japan, the United States, Germany and the United Kingdom.10

Australian tourism stands to benefit from these global developments.

We have also already seen a greater appetite for particular goods produced by Australian exporters. For example, while Australia's largest wine export markets continue to be the United States and the United Kingdom — and while there is currently pressure on this industry from the high exchange rate — wine exports to China have grown strongly, increasing from 1.9 per cent of total wine exports in 2007-08 to 6.1 per cent in 2009-10.

A sensible way forward

None of us knows with certainty for how long this mining boom will last. Nor do we know precisely what will be the shape of the global demand for Australian goods and services when it ceases. So it should be no surprise that economists have difficulty describing in any detail the industrial structure that will maximise economic opportunity for Australians in the world of the future.

One thing we can be certain of, however, is that it will not be the industrial structure we have

today, nor any drawn from our history. In the world of the future there will be no benefit to be drawn from turning back the clock.

Don't turn back the clock

Today's economy has responded much better to the mining boom than it did during any previous terms of trade spike. Three settings in particular have contributed to our flexibility and our ability to respond to the boom.

First, a flexible exchange rate has done a better job of curbing demand and price pressures.

Secondly, while Giblin addressed the problem of inflexible wages11, including in his Letters to John Smith, three-quarters of a century later, a significantly more flexible labour market has helped facilitate a reallocation of labour among sectors of the economy while avoiding economically damaging aggregate wage adjustments.

Thirdly, that sectoral reallocation of labour has been made easier by more open and flexible product markets nurtured by the dismantling of trade protection, deregulation of utilities and other components of the economic infrastructure, and the development of a sophisticated domestic competition policy.

It is important that there be no temptation to wind back the clock on the reforms that have helped get us where we are today.

Just as importantly, we should not allow ourselves to think that all the necessary reforms have been done. Giblin's Platoon understood the risks of complacency in their day. They were not carried away by roaring twenties euphoria. And with good reason. The Australia of the 1920s was overregulated and underproductive. As Brigden had said on a number of occasions:

The conditions of high tariffs, heavy borrowing overseas, and high standards of living are not conducive to enterprise or efficiency...People of all classes seemed to expect the Government not only spend for them but to think for them.12

In fact, Australia had not roared at all in the twenties. Rather, the 1920s were one of four decades in the 20th century to have had average annual GDP growth below that of the century average — along with the teens (which experienced the Great War), the thirties (which had the Depression) and the seventies.13

Reforms to facilitate a more flexible economy — an ongoing task

Today, I sign off after a decade as Treasury Secretary. In my last public address in that capacity, you might have expected me to be a little reflective. Yet I have chosen to look ahead to the economic landscape upon which future Treasury Secretaries will be developing policy advice for Australian governments. With those successors and future governments in mind, there is one reflection I will leave with you.

It is a reflection on political economy – of just the sort that pre-occupied Giblin in his day.

The hardest part of this job has not been figuring out what the 'right answer' to a policy problem actually was. I hope you won't dismiss as arrogance a reflection that, for a Treasury equipped with robust analytical frameworks, good evidence and capable of exercising sensible judgment, even very complex policy questions have, for the most part, proved tractable.

Thinking about present and future challenges, the 'right answers' for Australia today include: maintaining fiscal policy settings that lift national saving, including private saving, over time; pursuing further micro-economic reform, including tax reform, encouraging competition and improvements in education and health policies, to expand the nation's supply capacity by lifting participation and productivity and to promote economic flexibility; and constructing policy settings relevant to population that support an expansion of the nation's supply capacity, but in a socially and environmentally sustainable way.

On numerous other occasions I have detailed the reforms, in the areas of participation, productivity and population that could be pursued to lift supply capacity. I don't intend reprising those here. I do want to say, however, that most of them would do more than boost aggregate supply potential. Many would make a direct contribution to tackling the extreme capability deprivation suffered by many Australians, especially Indigenous Australians, and would deal also with the considerable forces that continue to threaten environmental sustainability on this vast land mass of extraordinary biodiversity.

Like Giblin, I think we do know what needs to be done. What we don't understand so well is how to get it done.

Right through the 1980s Australian policy makers, haunted by another deep recession attributable to policy failure over many decades, found themselves on a burning platform. With high inflation and high unemployment, and another negative terms of trade shock that threatened a further hit to living standards, the imperative for action was broadly understood and accepted. I'm not saying it was easy. It wasn't. And accounts of that period that would have you believe that it was not politically contentious – and I've seen more and more of these accounts popping up in recent years – are simply wrong. But the circumstances were so confronting that action was inevitable

Today we find ourselves having avoided a recession that paralysed the rest of the developed world. We have low inflation, low unemployment, and a terms of trade boom that has, to date, boosted average living standards. How does one, today, communicate the imperative for action? That is the question.

And the answer? Well, that is for you to figure out. To borrow from the man we honour today, Lyndhurst Giblin, in a letter to the prominent English novelist, E. M. Forster:

For God's sake, don't feel that [this] demands [my] answer. It is enough to have got it off my chest.

1 Coleman W, Cornish S, Hagger, Giblin's Platoon, Australian National University, 2006.

2 Griffin J (ed.), Essays in Economic History of Australia, p250, Jacaranda Wiley Ltd, 1967.

3 For example, industrial metal and machinery shed more than a quarter of its employees in 2 years (Yearbook, various years).

4 Sinclair WA, The Process of Economic Development in Australia, pp211-262, Cheshire Publishing Ltd, 1976.

5 Commonwealth of Australia, Economic Roundup Centenary Edition, 2001.

6 Giblin's Platoon pp113-114.

7 Volatility in global capital markets was also a concern of economists and the broader public.

8 For the services sector in Australia, 62 per cent of those employed in services between the age of 15 and 74 have some form of post school qualification in 2010. On the other hand, 54 per cent of those employed in manufacturing, agriculture and mining have post school qualifications. (ABS cat no 6227.0)

9 Stevens G, Address to the Committee for Economic Development of Australia, Melbourne, 29 November 2010.

10 UNWTO World Tourism Barometer, United Nations World Tourism Organisation, January 2011.

11 See for example his Letters to John Smith and the so called 'First Manifesto' (Giblin's Platoon p112).

12 Giblin's Platoo

n p110

13 Commonwealth of Australia, Economic Roundup Centenary Edition, 2001.