Downloads

***Check against delivery***

Introduction

Thank you very much for inviting me to speak this morning.

My topic is the 2014-15 Budget and its economic context. In the shorter term, the fiscal stance is little changed from the 2013-14 MYEFO, or indeed the 2013-14 Budget. The fiscal consolidation across the forward estimates, at an average of pace of 0.6 per cent of GDP, is calibrated to the prevailing macroeconomic conditions. Within that, the Government has made significant adjustments in spending priorities, particularly a shift from transfer payments to households and foreign aid, to payments to the states for infrastructure. It has also taken steps to streamline spending programmes and the shape of government agencies. Importantly, the Budget delivers a material improvement to our medium-term fiscal position. In doing so, it makes clearer some of the choices facing the Australian community over the next decade.

This morning, my aim is put some additional colour into the sketch I have just provided by looking at:

- the macroeconomic environment against which decisions were framed;

- the shape of the fiscal consolidation across the forward estimates;

- the magnitude of the medium-term fiscal consolidation; and

- the interactions between the fiscal challenge and the living standards challenge that we face.

Macroeconomic context

The Australian economy has sustained over two decades of uninterrupted growth. The economy demonstrated remarkable resilience during the Global Financial Crisis. Still, complex challenges lie ahead. As the investment phase of the resources boom fades and the population ages, growth in living standards will slow. For Australians who have become accustomed to strongly rising living standards, this will be a new experience. These structural changes will constrain growth in revenue and create additional spending pressures, particularly in health and aged care.

The more immediate backdrop for last week's Budget is an economy that is, in real terms, growing at a slightly below‑trend rate, as we transition from the largest resources investment boom in our history to broader‑based growth.

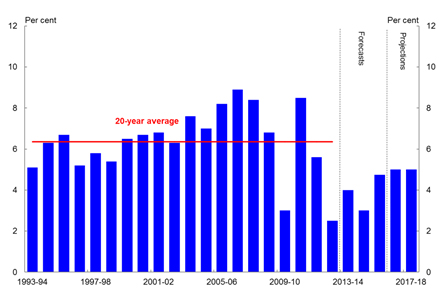

Chart 1: Outlook for nominal growth remains subdued

Nominal GDP is forecast to remain weak, growing by 3 per cent in 2014-15 and 4 ¾ in 2015-16, well below the average rate of growth over the past 20 years. This weakness in nominal GDP growth reflects the sharp fall in prices for Australia's key commodity exports since the start of the year, a further expected decline in Australia's terms of trade and subdued domestic price growth. It is nominal GDP growth, its level and composition that matter for tax revenue.

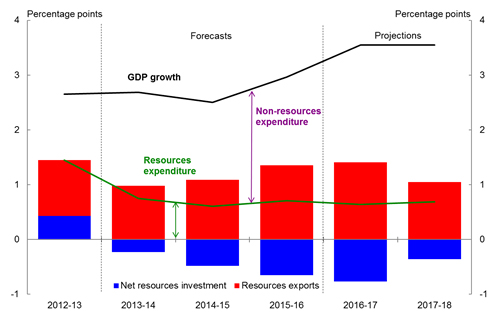

Chart 2: Contributions to real GDP growth

Over the past decade, mining investment has quadrupled its share of GDP, increasing from around 2 per cent to 8 per cent, and the capital stock in the resources sector is now three times larger than it was 10 years' ago. In recent years, resources investment has been a major driver of economic growth. However, from 2014‑15, resources investment is expected to start sharply subtracting from growth – the blue bars in the slide. While this detraction will be offset by increases in resource exports (the red bars), the total contribution of the sector to GDP growth (the green line) is expected to be much less significant than in our recent past. We need other sectors of the economy to take up the slack if we are to get back to trend growth and keep unemployment low, let alone start to bring the unemployment rate back down.

We are seeing some positive signs that the economy is starting to transition from the dependence on the resource sector, particularly in the household sector. But businesses remain cautious in their investment and hiring decisions and there are a range of forward indicators that suggest that it will be another year or two before broad-based growth takes hold.

Based on current forecasts, all this means that the economy will have been growing below potential for seven out of eight years to 2015-16. The resulting output gap is forecast to be the largest since the early 1990s.

The Government's medium-term fiscal strategy

Our experience through the Global Financial Crisis highlights the value in running a sustainable medium-term fiscal policy, in order to be in a position to deal with exceptional adverse shocks.

Sustainability is a difficult concept to define for governments, not least because a government's power to levy taxation is difficult to value, as are the expectations of the community for future government spending. So, even financial sustainability is difficult to determine precisely. And broader considerations, such as intergenerational equity, add to the complexity of the judgments involved.

Fortunately for officials, it is, ultimately, a government's job to make these difficult calls. But, having made those judgments, it is important for the government to articulate its fiscal objectives and the strategies that it intends to follow to achieve them. Under the Charter of Budget Honesty, a new government is required to publish its medium-term fiscal strategy no later than its first budget.

In the 2014-15 Budget, the Government set out its medium-term fiscal strategy of achieving budget surpluses on average over the course of the economic cycle.

The policy elements underpinning this strategy are:

- Investing in a stronger economy by redirecting Government spending to quality investment to boost productivity and workforce participation

- Reducing the Government's share of the economy over time, with the payments- to-GDP ratio falling and paying down debt by stabilising and then reducing Commonwealth Government Securities on issue over time; and

- Strengthening the Government's balance sheet by improving net financial worth over time.

To deliver on the medium term fiscal strategy the Government's budget repair strategy requires that new spending measures be more than offset by reductions in spending elsewhere within the budget and that positive variations in receipts and payments from favourable economic conditions are banked as improvements to the budget bottom line. It also requires a clear path back to surplus that is underpinned by decisions that build over time.

This budget repair strategy will stay in place until a strong surplus is achieved and so long as economic growth prospects are sound and unemployment low.

2014-15 Budget Position

In broad terms, the short-term fiscal stance in the 2014-15 Budget is unchanged from MYEFO and last year's budget. Looking through the one-off transaction with the Reserve Bank, the average pace of fiscal consolidation across the forward estimates is 0.6 per cent of GDP, one tenth of a percentage point faster than at MYEFO. The economy can accommodate this measured pace of consolidation without short-term adverse impacts.

The Budget supports growth in the short term by reallocating expenditure from consumption and foreign aid to infrastructure investment, where multipliers are typically higher. The Government's aim is to support infrastructure investment at a time when there will be excess capacity in the engineering and construction sectors.

In addition, the Budget includes measures that build considerable fiscal consolidation over the medium term.

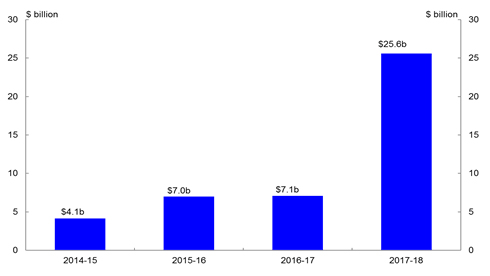

Chart 3: Improvement to the budget position since 2013-14 MYEFO

As a consequence of both savings that build over time and savings that take effect from 2017, real growth in payments in 2017-18 has been reduced from 5.9 per cent at MYEFO to 2.6 per cent and the ratio of payments to GDP is reduced by over 1 percentage point.

The pace of the current fiscal consolidation is projected to be slower than in the 1980s and 1990s. Underlying macroeconomic conditions are quite different. In particular, real GDP growth is likely to be slower than in the earlier periods; there is likely to be less fiscal drag, because inflation is lower; and the Government has fewer assets it could sell. (In the 1990s, asset sales helped reduce debt and public debt interest.)

At MYEFO, payments to GDP were projected to fall to 2016-17 and then pick up again in 2017-18 and across the medium term, rising to 26.5 per cent of GDP in 2023-24. That would have been more than one and a half percentage points of GDP higher than the 30-year average. The size of government is a public choice question.

In the Budget, the Government has taken a number of decisions that are directed at reducing the size of government in the medium term. They are consistent with its medium term fiscal strategy, which includes an objective of reducing payments to GDP.

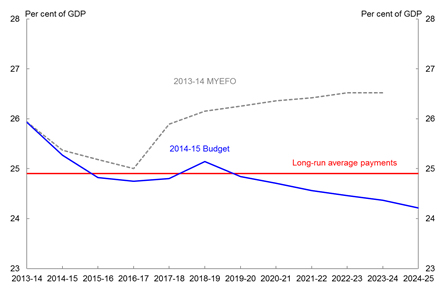

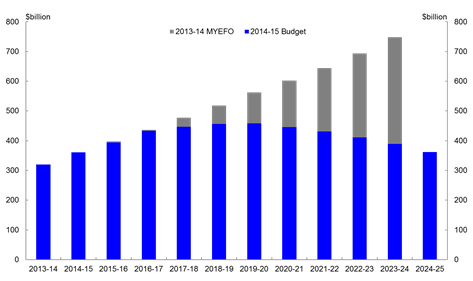

Chart 4: Payments projected to 2024-25

You can see that the effect of these decisions is to reduce payments to GDP from 25.9 per cent in 2013‑14 to 24.4 per cent in 2023‑24, the comparison point with MYEFO. It also shows the benefit of taking structural saves earlier in a period of fiscal consolidation.

These decisions, combined with an assumption of continued economic growth, return the budget to balance in 2018‑19, with surpluses growing to over 1 per cent of GDP in 2023-24, even when allowing for future tax relief.

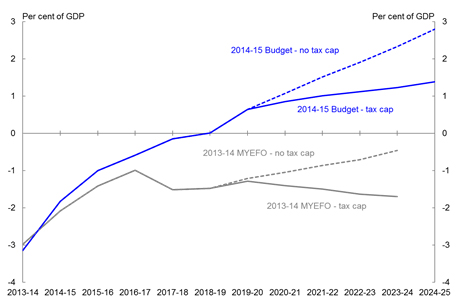

Chart 5: 2014-15 Budget and 2013-14 MYEFO projections of the underlying cash balance

The medium-term projection at MYEFO is shown on the chart. Importantly, there was no cap on the ratio of tax to GDP at MYEFO. Even with fiscal drag across the decade, the budget was still in deficit in 2023-24. The projection off the Budget base shows a considerable improvement in the fiscal position.

In the Budget, the Government has decided to provide for future tax relief, in effect returning fiscal drag after a time. This is both prudent and economically desirable. While it is difficult to assess the impacts of fiscal drag on participation on a year-to-year basis, there is little argument that higher marginal tax rates on lower and average incomes over time would have adverse impacts on participation. In addition, fiscal drag is regressive: the average increase in the tax take from lower income earners is relatively larger than for higher income earners.

You can see that after allowing for future tax relief, the Budget surplus rises to nearly 1.5 per cent of GDP by 2024-25.

The substantial improvement in our medium-term fiscal position delivered in the 2014-15 Budget has significantly reduced the projected level of gross debt.

Chart 6: 2014-15 Budget and 2013-14 MYEFO Gross Debt

When allowing for tax relief the Budget projected gross debt in 2023-24 to be $389 billion. This compares to $748 billion when allowing for tax relief at MYEFO.

Lower levels of gross debt will strengthen the balance sheet and improve the Government's flexibility to respond to unanticipated events during times of financial crisis or economic shocks.

Reducing the level of gross debt will also significantly reduce the cost of servicing this debt. The reduction in net interest costs is contributing to the improved budget position and the lower payments-to-GDP ratio in the middle of the next decade.

Productivity and living standards

The Budget was also framed against the recognition that population ageing and the likely path of the terms of trade mean that maintaining growth in living standards would require higher rates of productivity growth than we have achieved in the past. Budget Statement Number 4, which is the traditional "special topic" statement in the budget, focussed on sustaining strong growth in living standards.

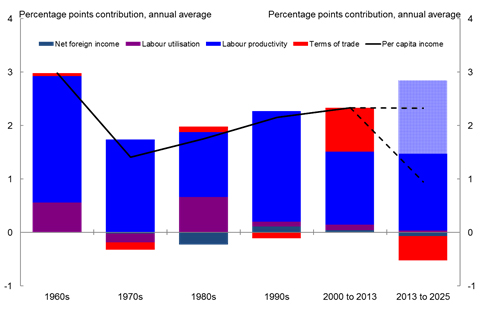

Chart 7: Sources of real Gross National Income growth

This chart sets out the challenge that we are likely to face over the next decade. The main sources of national income growth are productivity (the blue bars), changes in the terms of trade (the red bars), changes in labour utilisation (the purple bars) and net foreign income (the grey bars). The chart shows decade averages.

Looking ahead, we expect the declining terms of trade to detract from national income growth. Importantly, this projection is built on a steady decline across the decade. Should the terms of trade fall more sharply sooner, the detraction would be greater. If we were to achieve long-run average productivity growth, which is by no means a certainty, per capita incomes would grow on average over the decade ahead by around ¾ of a per cent a year, or about a third of the rates to which Australians have become accustomed.

The hatched blue bar illustrates the productivity growth that would be needed to sustain per capita income growth at recent rates. At about 3 per cent a year for a decade, productivity would have to grow at a sustained faster pace than at any time in the past 50 years, and at more than double the pace of the past decade.

This is a challenging outlook. In the Budget, the Government has redirected spending towards infrastructure and announced reforms to higher education.

These productivity enhancing measures are important, but further progress will be necessary if we are to maintain the income growth rates that we are used to. That will require further reform. History suggests that many productivity-enhancing reforms need fiscal support or, at least, that fiscal support makes reform easier to deliver. Placing the Budget on a more sustainable medium-term footing is worthwhile in its own right. But it could also help enable productivity enhancing reforms in the future.

Conclusion

As I have outlined, the 2014-15 Budget does deliver a substantial medium term fiscal consolidation. To achieve fiscal consolidation involves choices and that is why we elect Governments.

Recharging our fiscal buffers will provide policy flexibility should we confront another significant shock.

The improved medium term fiscal position presented in the Budget allows for future tax relief, which can avoid the adverse participation and equity impacts of fiscal drag.

And a stronger fiscal position could also help enable productivity enhancing reforms in the future.

Thank you.